Woman keeps promise to nurture Ugandan kids

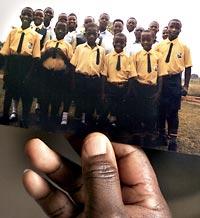

This 9-year-old boy is her favorite. Look at him in this photograph, smiling sly at the camera, his school uniform all out of whack. The green shorts sit lopsided on his hips. The pocket on his yellow shirt is torn. The striped socks are stretched unevenly on his shins.

"Every trouble, every problem, he starts it," said Emily Bourgeois, laughing at the photograph, taken in her native Uganda. "The most difficult human being you ever want to know."

Soon Bourgeois will take care of this boy, and 24 other children who live in a house she built years ago outside of the capital, Kampala. After raising two children of her own in the United States, Bourgeois is retiring next week from Group Health and leaving her apartment in Kent for good. The plan is to spend her retirement in Uganda, where she has fed, clothed and educated children from afar for so long.

"I was doing a puzzle," said Bourgeois, 63, recalling her decades of work with the children. "And this is the last piece of it."

In a country where so many people live in poverty, Bourgeois has helped dozens of children get their education. It is no guarantee of a better life, she said, but it is a start. The children she has helped have grown into teachers and nurses, designers and photographers. When one finishes school, she welcomes another one into the home.

Right now, Bourgeois is paying tuition for three children in university, three in college, four in high school, and the rest in grade school. Some of them are orphans. Others from families who can't afford the school fees.

Bourgeois was one of those children once. She was born and raised in a small village, sleeping three sisters to a bed. She wore the same dress every day, until the piece of clothing fell apart. She was 10 years old when the nuns brought her to boarding school — so skinny and small that no one believed her age.

The nuns taught her for years, then sent her on to finish her education at Seattle Central Community College. They never asked for payment. But Bourgeois made a promise to herself, soon after she graduated, to pay the way for others.

She has gone about that business quietly. Her daughter, Paula Bourgeois, said few people have known about the project in Uganda all these years. Emily Bourgeois also took some foster children into her home when her own children were small.

"She may not have enough money, but she's always able to make things better for other people," her daughter said. "She puts them before herself."

Bourgeois raised her own children with a strict sense of responsibility, reminding them how much others live without. Whenever they asked for something, Bourgeois would reply: Do you want it, or do you need it?

"Nine out of 10 times, they just wanted it," she said. "And they didn't get it unless they needed it."

Her work in Uganda started small, helping three children from the village where she was raised. Bourgeois paid their way through school, saving as much as she could from a well-paid job in marketing at Group Health. As she added more children to the circle, she started a side business to support them, renting out children's attractions at summer fairs.

Then in 1997, she took early retirement, returned to Uganda and built those children a five-bedroom home.

When her savings ran out a few years later, Bourgeois came back to America and found herself another job at Group Health. But she took a sharp pay cut working as a patient-care representative, earning about a third of her previous salary.

Between the job, and the side business, Bourgeois often worked seven days a week, trying to earn the $3,000 needed every month to support the children living in her house. The money pays for everything from medications to the salaries of the men who manage the house.

"I was flabbergasted," said Diane Cooper, who met her last year at St. Stephen the Martyr Catholic Church in Renton, where they are both parishioners. "She has this amazing amount of energy."

The women became friends and are now working to set up a nonprofit corporation. The goal is to raise enough money to expand Bourgeois' work — to educate more children, and to help children who are living with HIV.

The original plan was to wait until 2007, when she would have saved up more money. But a relative who oversaw the project died last year.

And the managers of the house can't cope alone with the problems that come with raising 25 children.

"As a parent, I need to be there," she said.

Bourgeois will leave in early December on the strength of her roughly $1,100 she will get monthly in Social Security.

She started a pig farm in Uganda a few years ago, and it may turn a profit down the line. But mostly she is pushing forward on faith, she said, convinced that the money will at some point come through.

"I can't tell these kids: 'Well, now things have changed,' " said Bourgeois. "We'll just have to find a way to survive."

Cara Solomon: 206-464-2024 or csolomon@seattletimes.com