Gates Foundation's agriculture aid a hard sell

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is dramatically expanding its efforts to help the world's poorest farmers, with goals every bit as ambitious as its better-known global-health work fighting diseases such as AIDS and malaria.

But the foundation's nascent agricultural program is encountering more resistance than much of its other work, with critics concerned that its market-oriented, technology-centric approach will open the door to big agribusiness interests and genetically engineered food.

The Gates Foundation began making grants a year and a half ago, spending $350 million so far. Its aim is to radically boost farm productivity in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia in a short time by introducing new seed varieties, irrigation, fertilizer, training for farmers and access to local and international markets.

The foundation explored how it could address poverty for about two years before settling on agriculture, seeing it as a natural extension of its work in health: It's no use curing disease only to see a child starve.

"This is not just about helping very poor people grow a little more food," said Rajiv Shah, the director of agriculture programs for the Gates Foundation. "This is about transforming agricultural economies so people can move on with their lives."

In the poorest countries, 65 percent of jobs are in farming. Yet Africa's share of food production is shrinking, and the number of people who are hungry is going up — in sharp contrast to improvements in the rest of the world.

Wars and drought are partly to blame, but so is a lack of assistance for farmers and investment in agriculture, Shah says.

In sub-Saharan Africa, more than 200 million people are hungry or malnourished — one-third of the population.

It's uncertain whether even the wealthiest private foundation can spur change where decades of aid and development work have failed and people have learned to distrust the rosy promises of outsiders. The wrong steps could end up exacerbating their problems, critics say.

"What is at stake here is the very future of the continent's agricultural practices — what is grown, how it is grown, who gets to grow it, who processes it, who sells it and ... how much the African consumer will pay," Kenyan political columnist Mukoma Wa Ngugi wrote in December in a critique of the foundation's work.

"Hot potato"

The Gates Foundation made its first foray into agriculture in 2006 with a $100 million grant to create an initiative with the Rockefeller Foundation called the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA).

Based in Nairobi, AGRA took as its model the original Green Revolution, which helped relieve widespread famine in the 1940s through the 1960s by boosting production of maize, wheat and rice in Latin America and Asia.

Part of the controversy lies in the Gates Foundation's choosing that approach.

Using strains of crops that required fertilizer, pesticides and irrigation, the Green Revolution methods increased yields. But they also damaged the environment, favored wealthier farmers and left some poorer ones deeper in debt.

Critics worry AGRA will repeat those mistakes in Africa.

"I wouldn't say [the Green Revolution is] universally reviled, but it's certainly a hot potato when it comes to agricultural development," said Britt Yamamoto, professor of Environment and Community at Antioch University Seattle.

"Personally I was a little surprised they would embrace that and not try to capitalize on the recognition that sustainable agriculture is possible and needs to incorporate politics and society to have a broader focus, not just a technical approach."

Eric Holt-Gimenez, executive director of Food First/Institute for Food Development and Policy, a California think tank, was more blunt. "It's a corporate strategy for colonizing Africa's food and agriculture systems, which thus far have resisted," he said.

Food First was among the sponsors of a weeklong conference in Mali in November to promote alternatives to AGRA, attracting 100 organizations concerned with maintaining local control over food.

In December, Shah flew to Portugal during an African leaders summit, meeting with government officials and activist groups who oppose the foundation's work. He said the exchange shows how the foundation is listening to its critics.

"It was a fantastic conversation," said Shah, a young medical doctor with an economics degree and background in health policy. "When you get people from all walks of life and different perspectives together in a room, we realize we all care about the same things."

Opinions vary widely on how to help the poorest farmers in the world — most of whom are women — escape poverty.

Catherine Bertini, who joined the Gates Foundation last June, spent a decade directing the U.N. World Food Program. She thinks there are two reasons why earlier programs haven't been successful:

"They've not been supportive of the roles of women, who are such vast players in agriculture," she said. "And they haven't done enough work at the community level understanding the needs before they start spending money."

Permanent solutions

At a village in rural Uganda recently, Shah sat on the ground with a group of women readying large, round banana-tree bulbs for planting. A staple crop, the banana trees had been suffering from bacterial wilt that cut fruit harvests in half.

Shah was trying to learn what might improve the women's lives.

A USAID government program to help them through the crisis was set to expire early this year, just one more well-intentioned project these farmers have seen come and go over the years, with nothing permanent to relieve their grinding poverty.

The women asked him to do something that would last. Back in Seattle, he took that as a fundamental lesson. "We talk about that every single day with every single project," he said.

The Gates Foundation initially focused on developing new seeds. But over the last year it has broadened its strategy to include what it calls the entire "agricultural value chain."

With an $8 million grant from Gates, the U.S.-based National Cooperative Business Association is organizing about 35,000 cotton growers in Mozambique, who typically work plots of 2 acres, to combine their harvests and sell to the world's largest private cotton merchandiser, Dunavant Enterprises in Memphis.

The five-year program, which Shah says is projected to raise the incomes of farmers from $225 per year to about $302 per year, also provides access to credit, literacy training and planting expertise.

The foundation is also backing irrigation programs, such as a low-cost drip system created by the U.S. nonprofit International Development Enterprise (IDE). It consists of plastic piping and a human-powered pump that operates with a foot pedal. The system reduces the cost of irrigation from about $6,000 per acre to about $37, IDE says.

Irrigation allows farmers to grow fruits and vegetables, improving their diet beyond subsistence crops. But only about 7 percent of the land in sub-Saharan Africa is irrigated.

Crop controversy

The area that has generated the most controversy is Gates' involvement in genetic modification of crops.

Through its global health program, it has helped fund $37 million in grants for genetic-engineering research aimed at developing plants that carry more nutrition.

One project by a team at Ohio State University is attempting to modify cassava, the starchy root that provides basic sustenance for millions in Africa, in order to increase key vitamins and minerals and extend its shelf life.

Another project by DuPont subsidiary Pioneer Hi-Bred, A Harvest of Kenya and a South African research council aims to genetically engineer a new variety of sorghum, dubbed "super sorghum," that has more vitamins and protein and is easier to digest.

In the future, drought-tolerant varieties of maize could lead to big increases in food supply and incomes of poor farmers in parts of Africa, Shah said.

The Gates Foundation, whose science-and-technology efforts are led by a former Monsanto researcher, is helping African governments develop biosafety standards and regulations and training local researchers in the latest plant breeding.

Such work is paving the way for "profit-hungry corporations vying to control the seed market in African countries," wrote Kenyan columnist Ngugi, "which will harm indigenous seeds and biodiversity."

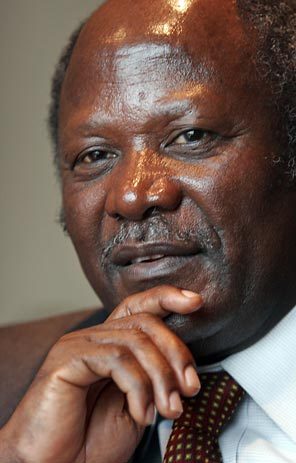

The situation was further complicated when former U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan, now chairman of AGRA's board, made a statement that African journalists interpreted as rejecting the use of genetically modified seeds.

The Gates Foundation later said Annan was misquoted.

Although the scientific data on genetically engineered crops and the legal framework to support their use in Africa are several years away, Shah said the Gates Foundation intends to pursue those options.

"We don't want to take anything off the table," Shah said. "Over time we will explore and use those types of technologies."

This worries Joshua Machinga, a Kenyan farmer who works with the nonprofit Common Ground Program. Farmers share local seeds with other farmers and cannot afford to buy seeds, let alone more expensive transgenic varieties that often require fertilizer and pesticide, he said.

"People do not know the hidden agenda behind it," he said, "that once they get the high-yielding seed, they have to keep buying it. Once you get in the system, then getting out becomes difficult."

Doug Gurian-Sherman, senior scientist with the Union of Concerned Scientists, said that while genetically modified crops might work in some situations, it's unwise to devote limited attention and resources to unproven technology when basic things like roads and storage and distribution are underfunded.

Ultimately, it will be a decision for African governments and farmers, Shah said.

"Our goal is to develop things that help small farmers lead better lives. If it doesn't help small farmers, we are not interested."

Kristi Heim: 206-464-2718 or kheim@seattletimes.com