Mistakes, some deadly, haunt county jails

King County Jail inmate Damon Henderson, suffering from sickle-cell anemia, refused repeatedly to take the methadone that a jail doctor had prescribed. It was the wrong drug for his joint pain, he said.

But Henderson was given the narcotic anyway, and died of an overdose in December 2003.

A month later, inmate Patrick Harrington, unable to sleep, asked for a doctor to treat his "very painful" infected and abscessed arm. Nearly two days later, he was finally seen at the jail clinic, where he collapsed, then was rushed to Harborview Medical Center.

Doctors found him infected by "flesh-eating bacteria" and stripped gangrenous tissue from his back and arm. Harrington died the next day.

Inmate Ronald Hicks should never have been able to squirrel away upward of 100 tablets of the antidepressant Elavil. Twice before, he had tried to kill himself in jail, and nurses were supposed to make sure he swallowed each pill they gave him. But they didn't, and in 2005 Hicks used his stash to kill himself.

These three deaths at the downtown jail were among the worst of hundreds of medical errors committed by jail health staff at King County's two jails. In 2005 alone, more than 600 errors were logged. Such mistakes can not only injure inmates but also create the need for more costly medical care and expose the county to possible lawsuits.

A Seattle Times investigation reveals a county jail medical system in turmoil. Among the findings:

In dozens of cases, jail health staff have denied needed drugs to inmates with illnesses ranging from HIV to seizures. Other inmates have not been adequately treated for painful illnesses and injuries. Jail health employees, from nurses to pharmacists, say they are overwhelmed and cannot properly care for patients.

Pharmacy staff, who have to fill hundreds of prescriptions a day, routinely have given out the wrong medicine. Drugs, including narcotics, disappear and cannot be accounted for. Jail pharmacies have failed three of eight state inspections since 2000, including a major inspection a year ago. The pharmacy at the downtown jail passed its most recent inspection in October, but not without extensive criticism. The other jail, in Kent, also has struggled in recent pharmacy inspections.

The U.S. Supreme Court has found that inmates -- many of them awaiting trial and not yet convicted -- have a constitutional right to medical care, including freedom from "deliberate indifference to their serious medical needs."

Shoddy health care at the jails exposes King County to expensive legal liability, said officials with the King County Ombudsman, the county's watchdog office, which began an investigation last fall.

"We believe there are systemic problems and deficiencies in Jail Health Services," Ombudsman Director Amy Calderwood said in an interview.

Other agencies are looking into King County's jails. The U.S. Department of Justice has begun a civil-rights investigation. And the Washington State Nurses Association, speaking for 80 jail nurses, said routine understaffing has created "serious concern" for the treatment of inmates.

Jail Health's medical director, Dr. Ben Sanders, would not discuss individual cases but said Jail Health is making extensive improvements, including streamlining access to medical care and investing $2 million in a computerized charting system.

The system isn't perfect, Sanders said, but inmates receive the care they need.

"This is a difficult setting, and I have to make clinical decisions as to how an inmate will be treated," he said. "Sometimes they don't like the answers. It's not like I go into the jail with the attitude of, 'Let me figure out how not to give people health care.' "

Even so, in the past three years, the Ombudsman charted nearly 200 inmate complaints. Senior Deputy Ombudsman Jonathan Stier said in a report to the King County executive and council in November that he believes the number substantially understates the problem.

In an October report, the Board of Pharmacy found that some drugs, including narcotics, still could not be tracked through the system from the pharmacy to the inmate as required by law -- this after six years of prodding by board investigators.

While Jail Health Services has strongly disputed both reports, Pharmacy Board Executive Director Lisa Salmi said the board stands by its findings and declared the issue "a top priority" for the coming year.

A struggle with costs

As part of a settlement of a class-action lawsuit 15 years ago, King County agreed to ease jail overcrowding and increase inmate access to health care. Yet the county has continued to struggle with costs and priorities.

On any given day, nearly 2,400 people are held in King County's two jails -- the 12-story fortress-like structure in downtown Seattle, and the sprawling Regional Justice Center in Kent.

Between 2001 and 2005, the budget for Jail Health Services shrank by more than $2.4 million, including 12 positions.

In 2006, the budget increased by $2 million, or 10 percent, to $22 million. But most of that went to increased drug costs. The department also cut the equivalent of nearly four full-time positions.

As part of the lawsuit settlement, the jail is inspected every three years to maintain accreditation from the National Commission on Correctional Health Care in Chicago. But while the jail has written policies that satisfy the commission, the implementation is inadequate, say state inspectors and officials with the Ombudsman.

For example, the commission requires Jail Health Services to ensure that staff document medical errors, investigate them and change procedures if needed. But Dr. Todd Wilcox, a consultant hired by Jail Health Services in 2003, found the department had no "medical management data" and thus "no way to monitor the system for quality."

In 2004, an HIV-positive inmate complained he was not given his daily cocktail of anti-retroviral drugs. Stier, from the Ombudsman's office, investigated and asked for treatment records.

For two years, the county insisted it could not provide the records, saying the information was exempt from public disclosure. Finally, Stier threatened to subpoena the documents. It was only then, Stier said, that Health Services' attorneys admitted the documents didn't exist.

The stonewalling "only served to obstruct and delay this investigation," Stier wrote to Jail Health Services last September, adding that it "casts doubt on the integrity" of the error-tracking program.

James Apa, a spokesman for Public Health -- Seattle & King County, which oversees Jail Health Services, says no one obstructed the Ombudsman's probe.

After numerous requests over several months, Jail Health Services released a summary of medical and prescription-drug errors for 2005 to The Seattle Times. It showed 614 reported incidents -- more than 90 percent of them medication errors. Jail Health Services was asked to provide summaries for other years, but had not done so as of Thursday.

But Jail Health officials also have pointed to one of the most significant changes it plans, the installation of a $2 million computerized charting system to replace the piles of paper charts now in use. That system should improve treatment and make errors easier to track.

Pharmacy problems

Jail Health Services has contended it should not have to comply with rules designed for pharmacies in hospitals, nursing homes or drug stores, saying jails have unique health problems, with transient populations and increased security issues.

Nonetheless, over the past six years, the state Board of Pharmacy has pointed out repeated problems. If jail pharmacies had been dealt with like those in other institutions, they likely would have been closed, said Pharmacy Board director Salmi.

In 2004, the downtown jail pharmacy failed a Board of Pharmacy inspection, partly because it was not logging adverse drug reactions -- when inmates are sickened by medication -- as required by law.

A year later, another inspection of the downtown pharmacy revealed that drugs -- including narcotics -- were being removed improperly from an automated drug-dispensing machine called an Omnicell, which looks like a file cabinet with drawers that can be accessed only by punching in a code.

Then, in February 2005, an inspector made a surprise visit to the Kent pharmacy and found: "[f]our inches of uncompleted medication error reports ... stacked on a desk, and staff reported that they had been told not to record incident reports regarding nursing and pharmacy errors."

The Jail Health employees also said errors occurred routinely, with prescriptions often given to the wrong patient, the inspector wrote.

According to a November 2005 inspection in Kent, a bag of "hidden medications" was found in the nursing medication room, and the pharmacist in charge, Anh-Thu Nguyen, reported a "huge backlog of incident reports that had not been written up, resolved or addressed."

The Kent jail pharmacy failed an inspection last June and Nguyen quit late last year, saying she "could not guarantee the safety of my patients."

One of her responsibilities -- tracking medications -- was impossible given the workload, she said. State law requires that she sign off on each prescription, a rate of about one every 75 seconds.

Every Monday, Nguyen would come to work to find "15 or 20" medication-error reports, she said. "There was no way to do it without making mistakes."

The methadone overdose of Damon Henderson likely resulted from a medication mix-up of the sort warned about by Nguyen and detailed in the Ombudsman's investigation.

The 36-year-old Henderson, in the downtown jail for allegedly violating a domestic-violence protective order, was being treated for joint pain stemming from sickle-cell anemia. Jail documents show Henderson complained about not receiving medical attention on Dec. 24, 2003. He became verbally abusive and spit on a guard. He was then placed under high security.

Henderson was pale, thin and had been "refusing his medications because they were the wrong medications," jail employee Vicki Shumaker said in a later, taped interview about Henderson. "He stated to me, 'They want to give me methadone. I don't take methadone. I keep telling them that.' "

On Dec. 29, he was given methadone anyway. The next morning, he was found dead sitting on his bunk, a pool of vomit between his feet.

An autopsy and investigation showed that the lethal dose given to Henderson was likely calculated to relieve withdrawal symptoms for a heroin addict, not for someone with no tolerance for the narcotic.

Jail Health Services would not comment on Henderson's case or any of the others.

Writing "kites"

The 2004 death of inmate Patrick Harrington underscores two problems: Jail Health's response to cases of antibiotic-resistant staph infections, and the system inmates use when they want to see a doctor.

In the year before Harrington died, the reported number of resistant staph infections in the King County jails exploded from 291 to 623.

Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a bacteria that is resistant to treatment by usual antibiotics. In most cases, it appears as a draining pimple, boil or skin infection. Jail Health officials say the numbers are higher because they've become better at identifying infections.

Harrington, 40, was booked into the downtown jail on Jan. 20, 2004, for allegedly violating a domestic-violence protective order. His sister, Elsie Villalovos, said Harrington had struggled for years with drug addiction. Documents indicate he had been injecting drugs about 10 days before his arrest.

Drug users sometimes get infections at sites of their injections. During an initial jail health screening, there was no mention of an infection. Early on the morning of Jan. 22, Harrington submitted a "kite" -- a written request to see a health-care provider.

Kites are placed in boxes around the jail and reviewed by a nurse, who determines who will be seen when. A common complaint to the Ombudsman is that kites are ignored and that it can take days, even weeks, before being seen in the jail clinic.

Harrington's kite was stamped as received in the clinic on Jan. 23 at 9 p.m., apparently more than a day and a half after he filled it out. In a rough scrawl, Harrington had written: "I have two abseces [sic] they grew [indecipherable] in very painful it has leak some [indecipherable] sleve."

Harrington was brought to the clinic at 9 a.m. on Jan. 24. A nurse wrote that the inmate's red-streaked shoulder and arm were "taut to the point of feeling like wood" and "red hot" to the touch.

Harrington collapsed in the clinic and was sent to Harborview. There, he underwent emergency surgery, with doctors stripping away huge pieces of his shoulder and back, exposing the bone in his arm, as they raced to get ahead of the flesh-eating bacteria raging through Harrington's system. He died early the next day. An autopsy found a resistant staph infection.

Jail Health officials still use the kite system, but an inmate also can verbally ask to see a doctor.

The Department of Justice now is looking into the problems with MRSA infections as part of its civil-rights investigation at the jail.

"I'd rather die quickly"

The case of Ronald Hicks demonstrates another key shortcoming in the jails: a lack of monitoring to ensure inmates are given -- and take -- their medicine.

The 43-year-old Hicks was facing a three-strikes life sentence after a failed robbery at a gas station in January 2002. With prior convictions for robbery and rape, Hicks' history included alcoholism, anxiety disorder and depression. He had tried to commit suicide in the jail twice before.

When he was sentenced on Dec. 1, 2003, Hicks begged the judge for a death penalty.

"I'd rather die quickly rather than to die thinking for a long time about dying," he said.

The next morning, he was found unconscious in his bunk after overdosing on the anti-depressant Zyprexa and Tylenol. He was taken to Harborview Medical Center, where he recovered. On Dec. 8, he was sent back to the downtown jail with an order requiring "constant watch."

For two days, he was isolated and checked every 15 minutes. But then he was moved to the general population, without extra oversight. He later was sent to the state prison in Shelton, but in June 2004, was returned to the downtown jail to await the outcome of his appeal. There was no reference to his prior jail suicide attempts on his jail-health screening form.

For the next year, he continued to receive pills for depression. For an inmate like Hicks, who had secreted pills before, nurses were supposed to inspect his mouth to make sure he hadn't "cheeked" a tablet in order to retrieve it later.

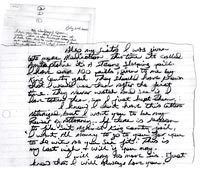

On June 20, 2005, his appeal was rejected. The next day, Hicks wrote his sister, Susie Perry of Portland: "I love you Sis. And I miss you already. This is the hardest letter that I have ever had to write, Susie ... [but] I truly need you to know that I AM AT PEACE.

"I was given lots more medication this time. ... It's called amitriptyline it's a strong sleeping pill. I have over 100 pills, given to me by the King County Jail. They should have known that I would use them after the first time. They never watch me to see if I have taken them, so I just kept them."

Hicks was found dead in his bunk the next morning. An autopsy showed he had taken at least 80 tablets of the drug.

Report to county

Last November, following a critical pharmacy inspection the previous month, the Ombudsman sent the King County executive and County Council a negative report about Jail Health Services.

Jail Health officials sharply countered the report, claiming the Board of Pharmacy's findings contained inaccuracies and were an attempt to force the jails to comply with unfair standards. The County Council was given a 2-inch-thick binder with Jail Health's rebuttal.

Public Health -- Seattle & King County lawyers again complained to the Board of Pharmacy that it was unfair to judge a jail pharmacy by rules set up for general-use pharmacies.

The Pharmacy Board agreed and adjusted the score given the pharmacy, but did not withdraw its criticism. The Pharmacy Board and jail now are developing policies specific to jail pharmacies.

Meanwhile, Jail Health Services Director Bette Pine insists the jail has made progress in the past two years and that at least some of the criticism is unwarranted. Additionally, she and Medical Director Sanders are pushing extensive changes aimed at improving inmate health care, from changes in health screening when an inmate is booked to the planned electronic charting system.

"I'm not going to tell you there are no problems, that there are no issues. They are a fact of life," Sanders said. "What I will tell you is that we are making systemic changes to address them."

Even so, Jail Health still faces challenges. There were the 614 incidents in 2005. Then there are the ongoing investigations by the Ombudsman, the Board of Pharmacy and the Department of Justice. This week, Justice investigators were at the county jails to look into claims of inadequate suicide prevention and contagious-disease control.

The Pharmacy Board will not let up on its oversight, said its director, Salmi.

"We are still concerned about patient safety," she said.

Mike Carter: 206-464-3706 or mcarter@seattletimes.com

Average daily inmate population for both jails in 2006: 2,397.

For the past three years, the average daily population of inmates under medical care in the two jails has been 116, and the average number of inmates under psychiatric care per day has been 97.

Jail Health Services filled 193,141 prescriptions in both jails in 2006.

Jail Health Services employs the equivalent of:

Doctors: 5.5

Nurses: 59.3 registered nurses, 16.4 licensed professional nurses, 7 nurse practitioners, 1.5 public-health nurses

Psychiatric evaluation specialists: 10

Pharmacists and staff: 2.5 pharmacists, 8.75 technicians and supervisors

Social workers: 3

Other staff: A disease-control officer, a disease-prevention specialist, one part-time dentist and three dental technicians.

Sources: Seattle-King County Department of Public Health and the King County Department of Adult and Juvenile Detention