A web of giving

When Jeanne Ting Chowning went shopping online for her mother-in-law this year, she looked for an unusual kind of gift.

Instead of searching for a sweater that matched her style, she looked for a project that matched her values.

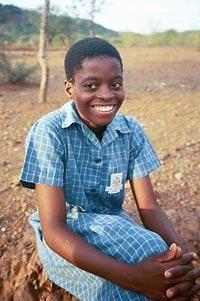

Through an organization called GlobalGiving, Chowning found a charity in Zimbabwe, where her gift of $25 helped an impoverished girl pay school fees for a year, buy a uniform and have hot meals.

Chowning, who works for a Seattle nonprofit and has a limited budget for philanthropy, liked being able to choose from hundreds of projects on the GlobalGiving Web site. They range from improving health care for mothers in rural Tibet to helping revitalize small businesses in poor areas of the Mississippi River Delta after Hurricane Katrina.

"It's so much more convenient to do this way. By bringing together all the different organizations, you can browse and compare," Chowning said. "You can customize your donation to align with the things that interest you."

Technology is changing the way people approach philanthropy. Call it Philanthropy 2.0. The power of the Internet not only makes it possible for donors to find organizations and causes they support around the world, but it means that even small amounts by individuals can make a big difference because of the sheer volume of givers.

"EBay revolutionized shopping, and the iPod revolutionized music," said Dennis Whittle, chief executive of GlobalGiving, who co-founded the nonprofit in 2000. "Now the Internet is revolutionizing part of philanthropy."

The Internet links the donor and the recipient in new ways. GlobalGiving, for example, allows Chowning to e-mail the project coordinator in Zimbabwe, see photos and messages from the students and receive updates from the field throughout the year.

Such Web-based features "make you feel a connection with a community far away that's not possible with a brochure," Chowning said.

Connection inspires

That kind of connection also inspired Patsy Glaser. Glaser, a senior citizen on a fixed income, has donated to charities most of her life, yet giving money to some large organizations left her unsatisfied.

"You never get reports about what's going on," she said. In a few cases, she found out later her donation wasn't going where she intended.

Now she does most of her philanthropy online, donating as little as $10 at a time through GlobalGiving to help programs in the Darfur region of Sudan.

One of them funded the training of women to build simple, fuel-efficient clay stoves, while another provided food and care to save thousands of donkeys, critical for transportation and livelihood.

Glaser is also loaning $25 at a time to aspiring entrepreneurs through Kiva.org, a Web site that connects individual lenders and borrowers worldwide.

Kiva's founders wanted to build on the microcredit concept pioneered by Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus. While they found many microfinance institutions lending money to poor people, none allowed people with average incomes to participate by loaning small amounts of their own money.

"Philanthropy used to be balls and receptions catering to high net-worth individuals," said Kiva President Premal Shah. "I think there's something democratizing if you can bring technology into it and let the average person be like a Bill Gates or a Rockefeller."

Their solution was to fill the Web site with profiles of individual entrepreneurs, vetted by local microfinance partners, and create an easy way for anyone to sponsor their businesses.

"I like the fact that you can pick out the people," Glaser said. "You read about all these people and what they need and where they live. I hone in on women with children."

From her home in Fircrest, Pierce County, Glaser spends several hours a day online, which has allowed her to follow the progress of Beatrice Wanjiru Njuguna, a 47-year-old mother of six who grows and sells vegetables in Kenya.

To improve her small farm, Njuguna applied for a loan of $300 through Kiva this summer, and Glaser was among the lenders.

Glaser receives e-mail updates about Njuguna, who expects to double her income this year and has already repaid a third of the loan on schedule.

"She's doing good, and I'm really proud of her," said Glaser, the retired owner of two travel agencies in Tacoma.

18,000 lenders

Kiva, named after the word for "agreement" in Swahili, has been operating for a little more than a year and has attracted about 18,000 lenders contributing an average of $82.

Lenders put in funds using an online payment method like PayPal, and Kiva transfers 100 percent of the amount to a local microfinance institution, which distributes the money to the borrower and manages the loan.

While the system relies on trust, it has proved its effectiveness over time because "you get your money back," Shah said.

So far, about 116 loans have been completed, and Kiva's repayment rate is 100 percent. Lenders receive no interest for the loan. Still about 85 percent of the funds have been reloaned for a second year.

"It's just mind-blowing to a lot of people you can actually give someone you've never met money," said Shah, a former product manager at PayPal. "But 10 years ago it was mind-blowing that someone on eBay could buy a TV from someone they never knew."

The local microfinance institutions Kiva works with charge interest to borrowers to cover operating costs, with rates averaging about 19 percent, Shah said. Interest rates in the microfinance industry overall are higher, averaging 30 percent.

Kiva posts information about the performance of each of its microfinance partners on its Web site.

San Francisco-based Kiva has managed to keep its own operating costs low — it has spent just $320,000 so far among seven employees, raising $1.5 million in loans to 2,600 people. PayPal offers its services to Kiva free of charge, Google provides free advertising and Microsoft Research funded and conducted a project in East Africa to determine the best technologies to facilitate microfinance using Kiva.

GlobalGiving, based in Washington D.C., also strives for a lean operation. The nonprofit has 15 full-time and three part-time employees. It has directed donations to more than 700 projects in 85 countries and has given out $4.25 million in donations since 2001.

For every dollar that comes in, 85 to 90 percent goes to the project on the ground, while the remainder supports GlobalGiving's operations and pays for money-transfer fees.

While GlobalGiving's operating costs are fixed at 10 percent, Whittle said, nonprofits typically have a much higher overhead.

Whittle makes $150,000 a year, but neither he nor his partner took any salary for the first two years. They have relied on $4 million in seed capital to cover costs and hope to break even within the next five years.

Whittle worked for the World Bank for more than a decade. He led the unit that created the Development Marketplace, a competitive grant program that funds small-scale projects at the grass-roots level.

That effort showed the potential of a bottoms-up approach, persuading him and colleague Mari Kuraishi to strike out on their own with GlobalGiving.

Bonus of technology

While technology is increasing the transparency of nonprofits, it's also dramatically reducing the cost of information, Whittle said.

In the past, someone who wanted to submit an idea for a project would have to mail it and wait months or years for it to be evaluated and funded.

Using the Web, GlobalGiving works with 40 sponsors around the world, including Seattle-based Agros International, allowing most projects to be posted within a few days.

"We want to enable people to directly connect with as little interference from us as possible," Whittle said.

That adds up to more choices for people like Jan Cavitt. A retired career counselor from Seattle, she gave friends and relatives a surprise last Christmas.

"Everybody got mosquito netting," she said. They went to poor families in Tanzania to help protect them from malaria.

Though unusual, the gifts were well-received, she said. "They were all just grateful that something good was being done," she said.

This year Cavitt said she will select a different project for the people on her list.

"Our family members don't need things from us now," she said. "They are all comfortable adults, and they've agreed that this is a far preferable way to receive gifts than to be given something they can't use or don't like."

Kristi Heim: 206-464-2718 or kheim@seattletimes.com

Where to give![]()

![]()

Web sites that make philanthropy easy

• Kiva.org