Fur back in business and in trouble

In a drab conference room in a nondescript Renton warehouse last spring, an auctioneer took a podium beneath huge photos of supermodels in mink coats and fur lingerie. He turned on his microphone and began soliciting bids.

Before him, dozens of men and women buzzed in a babel of foreign languages — Russian and Italian, Chinese and Korean. But their common language was hanging on racks in the room next door: some 1.7 million shimmering pelts of farm-raised mink, and hundreds of thousands of wild beaver, raccoon, weasel and fox.

This is the American Legend auction, the largest remaining fur market in the United States, where $100 million in business is transacted in a few days.

Much as they have for more than a century, merchants from all over the world come to Western Washington to pick over silky skins of North American mammals on behalf of garment manufacturers who will produce next year's lines of boots, hats, gloves, scarves, blankets and coats.

After a few rough decades, fur is back. Spurred by a boom in demand from China and recent popularity at home thanks to glossy marketing, the price of American mink pelts jumped 33 percent just last year.

Yet a trade that helped put Seattle on the map today takes place largely out of view, in a heavily guarded, fenced-in warehouse protected from anti-fur protesters. And there's an entirely new unease: Two years ago, a handful of buyers from New York, Canada and China hatched a scheme to rig bids and buy hundreds of otter pelts on the cheap, according to federal prosecutors.

That led to a long-running Justice Department antitrust investigation that may still be in the works. Federal prosecutors remain mum. But class-action lawyers are circling.

And once again the fur trade faces the prospect of being drawn into an uncomfortable spotlight.

"Everybody's nervous right now, because they don't know what's coming next," said Sandy Parker, a New York journalist who has published a newsletter on the fur industry for more than 40 years.

Fur sales suffer, rebound

On an average weekday last May, buyers strolled through a chilly stockroom in the Renton warehouse. As the auction was being prepped in the next room, workers in lab coats hauled garment racks full of colorful, farm-raised mink hides to brightly lit counters for inspection.

Nearby hung a showpiece, a mink coat that supermodel Elle MacPherson once wore for an ad, constructed from 45 pelts of top-of-the-line blackglama mink, which can sell at auction for $1,300 apiece.

All around, buyers ran fingers through the soft hair of the pelts, looking for flaws, and scribbling notes in auction catalogues.

The fur business is a lot different than it was in the 1780s, when English explorer Capt. James Cook first got sea-otter pelts from Northwest tribes and sold them in Asia, launching a trade that became as integral to the Pacific Northwest as salmon and trees.

Nowadays, Denmark rules the fur industry, selling 80 percent more mink than the U.S. Garment manufacturing is ruled by Asia, rather than New York. Expanding markets in China, Korea and Russia are helping drive new demand.

It wasn't always so.

Fur was becoming controversial as early as the 1960s, and by the 1980s and early 1990s it was the target of sabotage by animal-rights activists, who vandalized stores. In 1991, activists burned a small Edmonds factory that made feed for farmed mink. All over the country, mink were sprung from their cages, and farms were raided, even torched.

In addition, there were economic troubles in Asia and a glut of furs. Prices crashed.

To resuscitate the business, American Legend, a cooperative of 220 North American mink ranchers, undertook advertising campaigns, hiring supermodels Cindy Crawford, Gisele Bundchen and MacPherson. They capitalized on exploding Westernization and wealth in Asia brought by a rejuvenating economy.

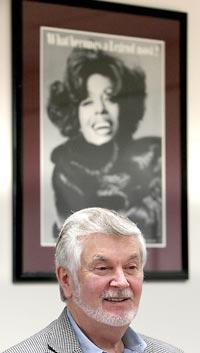

"Beginning in 1999, we tried to refocus the industry and consumers that [fur] could be an integral part of fashion," said Steve Casotti, vice president of American Legend.

While protesters continue to commit acts of eco-sabotage, and to portray the fur industry as cruel, inhumane and unnecessary in the modern world, celebrities such as rapper Sean "Diddy" Combs and pop singer and actress Jennifer Lopez are now seen and photographed in mink coats. In places such as Korea, China, Russia and Turkey, the rich are "driving expensive cars, wearing Rolexes and buying fur," said Alvin Glickman, a fur buyer in New York.

Now the fur industry is so global that some Native Alaskans buy wild-animal skins through Renton furriers to make traditional clothing, some traders say.

In fact, the Puget Sound region is the country's primary link to fur. American Legend is the country's biggest seller of mink, hosting international auctions twice a year, in February and May, drawing hundreds of buyers from up to 20 countries.

And for one day each February, Canadians take over the Renton auction house and sell hundreds of thousands of furs from wild animals — squirrel and coyote and lynx and otter — that were mostly trapped in Alaska or the Canadian territories.

Still, a surprising share of this business is conducted as it always has been — mostly by well-traveled men, capitalizing on personal relationships, shouting out bids and sweating out the pressure in a room where $4 million can change hands in seven minutes.

And that's where the trouble began.

Allegations of collusion

On February 13, 2004, just before the Renton wild-fur auction, a gruff but well-liked New Yorker named David Karsch, a fixture on the international fur-buying scene for decades, was approached by a woman.

"They want to talk to you," she told him, according to court documents, and she led him to a lounge set up for fur buyers at the auction house. It was a private meeting with some of his competitors in the fur business.

Otter furs were suddenly fashionable in China, so the traders all agreed that Karsch would buy several "strings" of otter pelts, and split them with his competitors after the auction, according to court records. That would could keep prices down because few would bid against him.

But it also was a federal crime: collusive bidding, or price-fixing.

Someone happened to overhear the conversation, and passed it on to auction officials, who took note when Karsch bought $46,000 in otter furs.

Buyers were already on edge. Rumors of bid-rigging scams had circulated among fur brokers the previous fall.

And American Legend was changing its system. After the 2003 SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) epidemic threatened to disrupt international travel, the auction house had planned to introduce an electronic bidding system, so buyers eventually could buy furs without leaving home.

It is a point in history when "you can buy a Monet on eBay," said Ed Brennan, president of American Legend. It was time to merge the past with the future.

But many fur buyers have a foot in the past. Many are in their 70s, or have been in the business for decades. Some were uncomfortable with computers. Others feared they wouldn't get to see who they were bidding against.

Several threatened a boycott. The auction house withdrew its plans.

Then things got worse.

During the May 2004 auction, FBI agents hand-delivered dozens of subpoenas to fur buyers at their hotel rooms. Some foreign buyers were alarmed and confused. One buyer said he saw another chase an auction official around a table, trying to hit him.

Eventually, a grand jury in U.S. District Court in Seattle indicted Karsch, 76, charging him with restraint of trade. He pleaded guilty this summer, even though he made less than $1,500 on the otter-pelt sales. He faces up to three years in prison, and a fine of up to $350,000. His sentencing is scheduled for this fall.

But it's too soon to say whether the chaos is over.

"The whole thing is still at the forefront of everybody's mind," said Glickman, the New York fur buyer.

Under questioning from federal prosecutors, Karsch said he had passed up other schemes to rig bids, in 2001 and 2002, because he "didn't want to go to jail," according to court documents. Federal officials won't say whether they're done investigating.

In January, a few former mink ranchers filed a class-action suit against several mink buyers, alleging widespread bidding collusion to hold down prices. The ranchers' attorneys won't discuss their evidence. But one buyer is cooperating and has given over records.

Gregory Hansel, a Maine attorney for the mink ranchers, said they intend to prove that, just like in the Karsch case, several bidders agreed in advance about who would bid on certain lots, holding prices artificially low.

"Auctions are supposed to be the perfect model of the marketplace," Hansel said. But "we've interviewed a number of people in the industry, and we believe this conspiracy affected mink auctions in particular."

Attorneys for the buyers did not return calls for comment.

For the auction house, the investigation was a blow. Amid the turmoil, many foreign buyers threatened not to return to Seattle. American Legend, for the first time, moved its 2005 auction out of the country, to Vancouver, B.C.

"We were getting punished, and we're an innocent victim in this thing," said Dick Clinton of Seattle, an attorney for American Legend.

Even so, with accusations swirling, more than 340 buyers showed up in Vancouver and paid record prices.

Earlier this year, American Legend officials persuaded the Justice Department to promise not to serve subpoenas or come around asking questions if the auctions moved back to Renton.

At its homecoming in February, American Legend sold $104 million in fur — in two days.

In 1999, it had sold $65 million the entire year.

An uncertain future

Yet, in such a cyclical profession, many still wonder about the future.

In the early 1980s, there were 1,200 mink ranches in the U.S., producing twice as many furs as are produced today. Even that was about half what was produced in the 1960s.

Many farmers are getting on in years. So are many U.S. brokers. And it's not an easy business.

Irwin Goldberg runs a small, family-owned fur-trading business in Renton, H.E. Goldberg & Co. The company has dealt in coyote, muskrat, fox, otter and nutria in the Seattle area since 1919. It once was seven or eight times its size.

Goldberg is now in his 80s, and he has scaled back significantly. He worries whether he can pass his business on to someone. His children, he said, have no interest.

"Without people stepping up to do what used to be so central to our past, there may not be an H.E. Goldberg anymore," he said.