1800s diary tells of murder mystery, life on Eastside

Clarissa Colman stood at the window of her Kennydale home and watched her husband row his boat around the southern tip of Mercer Island, heading to Seattle.

When he didn't return that night as expected, she didn't worry. In 1886, business in Seattle sometimes took more than a day. Or he might have been delayed by the anti-Chinese riots that were filling the newspapers.

"I had not thought at that time that evil had happened to him," she wrote in her diary.

The evil that befell James Manning Colman and a young friend, Will Patten, was murder.

Someone ambushed the two shortly after they reached the western side of Mercer Island. They were shot at close range, their bodies dumped in shallow water.

To cope with her grief, Clarissa Colman began keeping a journal.

One journal followed another for the next 24 years, each chronicling the daily doings of a busy pioneer farm widow as she coped with personal loss, local change and the broader events impacting the region.

The diaries were recently given to the Eastside Heritage Center by Colman's granddaughter and great-grandsons.

For Eastside historians, the books are the equivalent of the Lewis and Clark diaries.

"These aren't the stories you get from history books," said Heather Trescases, executive director of the Eastside Heritage Center. "Firsthand accounts tell you what life was really like. And a handwritten account from a woman in a farming community is not common at all. From an historian's perspective, this is a fabulous resource."

In effect, Clarissa Colman recorded history from the viewpoint of her front porch.

She wrote about watching the glow of the flames and the smoke from the Great Seattle Fire of 1889. She observed Native Americans paddling up and down Lake Washington in dugout canoes, and notes the day a group stopped by her house to ask for matches. She remarked on U.S. presidential politics and her own first vote in a territorial election:

"As the country seems to be going to the bad, I think I will have to do all I can to save it," she wrote.

Through a telescope, she watched boat traffic on Lake Washington, identifying small steamships by name and marking the shipments of logs and coal that floated by on barges. Colman, no relation to the namesake of Seattle's Colman Dock, recorded the deaths of Seattle pioneer Henry Yesler and Princess Angeline, the daughter of Chief Sealth who helped the first settlers when they arrived in Puget Sound.

But mostly she wrote about her daily life and that of other Eastside pioneers who were her friends, including the Albert Burrows family, whose log cabin still stands on the edge of downtown Bellevue.

She wrote until a few days before her death at age 77, in 1910. Her son, George Colman, and daughter-in-law Margarete briefly added to the journals. By the time Margarete put the books aside, the family had filled seven volumes dated 1886 to 1916.

They're standard journals of the time, some canvas-bound with leather corners, about 8-by-10 inches and a half-inch thick. The ink is still clear on the lined pages.

Some entries are hard to decipher. There is no cast of characters, no explanation for some things. Colman wrote for herself, not for posterity.

No known photographs of her survive.

Hard, busy life

For the student of history, the diaries document the economic realities of the late 19th century. After 1893, when a financial panic almost as bad as the Great Depression of the 1930s swept through the country, Colman's diaries reveal a big increase in people knocking on her door and asking for supper.

The pages describe a hard, busy life — making soap, and yeast for bread baking, frying cakes, roasting coffee beans, sewing clothes. She blackened her stove to preserve it, painted the house, washed and ironed, planted and picked.

She was a tough, practical woman who suffered from frequent headaches and had a wry sense of humor, peppering her journals with puns and ironic comments.

And she was a sharp businesswoman. She and her sons sold beef, pork and hay — plus the fruits and vegetables she grew and nearly all the butter she churned — to the company store that supplied food for miners at the nearby Newcastle coal mines.

She writes about receiving interest from people after she'd loaned them money, and notes the time she advanced a son-in-law $125 — a huge amount considering she complained when her property taxes were almost $100. After her husband's death, she invested in house lots in Seattle.

She was also feisty, successfully suing a railroad that wanted some of her land for a right-of-way.

Then there are the poignant moments — the death of a grandchild, a period of estrangement from her youngest son, and her loneliness after the murder of her husband, James.

The murder remains unsolved. James Colman had been subpoenaed to testify against George Miller, a homesteader who was accused of claiming homestead land in the names of several minor children, an illegal but common act. Colman was rowing to Seattle to testify when he and his passenger, 14-year-old Will Patten, were shot and killed. An investigation implicated Miller. He was tried three times and finally convicted, but eventually the state Supreme Court threw out the case, citing a lack of sufficient evidence.

The murder deeply affected Clarissa Colman. On Nov. 16, 1886, as she and her daughter were coming home from Miller's trial, she wrote:

"This is the anniversary of our coming to Washington Territory. Eleven years today and the same day of the week. But what a difference. Then we were all together ... What a sad homecoming. How terribly lonely. How can I endure it."

Endure it she did for another 23 years. She became the matriarch of the family, keeping the family business going, preserving the several acres that she alternately called "The Farm" and "The Ranch."

She built a second, larger house in the 1890s, a short distance from the first, and at times rented out one or both. Two sons worked on steamships that plied Puget Sound, Lake Washington and Lake Sammamish; a daughter taught school; and everyone farmed part of the time.

Clarissa Colman's last entry was Jan. 24, 1910. A few days later her son George made this entry: "Mother was taken sick on the morning of the 25th of Jan. 1910. Dr. Mitchell called in ... [She] died on the 28th of Jan. at five o'clock in the morning."

House now condominium

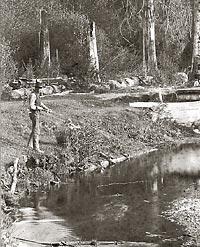

The original Colman home was located just north of the Barbee Lumber Mill, in what is now Renton. May Creek cut through the property. The family retained most of the property until 1943, when heirs sold all but the original house. Today the house is gone and a waterfront condominium sits on part of the land.

Granddaughter Clarissa Colman Fawcett was given the diaries by her mother, who lived in the original Colman house.

Jackie Smelser, a local historian, encouraged the family to donate the material. When they did late last year, the surprise to the heritage community was the number of years the journals span.

Lorraine McConaghy, a historian with the Museum of History & Industry in Seattle, said she knew of only two other female diarists who recorded that era of Washington history: missionary Mary Richardson Walker, who wrote of her experiences in Eastern Washington and Oregon from 1833 to 1878, and Phoebe Goodell Judson, who wrote the autobiographical "A Pioneer's Search for an Ideal Home" from her experiences leaving Ohio in 1853 to travel the Oregon Trail and eventually settle in Lynden, Whatcom County.

"We have nothing else this early to document and identify the Eastside," Smelser said. "She covered things from row boat to automobile."

Indeed, the year before she died Clarissa Colman wrote about her son George waiting for delivery of his first automobile. After it arrived on Sept. 6, 1909, she went for long rides in the car. One Seattle stop was the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, a world's fair held on the University of Washington campus showcasing the development of the Pacific Northwest.

Colman's great-grandson Robert Fawcett, who grew up in Kennydale, still remembers hearing the stories of his family's pioneer days and playing on the same land his great-grandparents farmed.

"The cow barn was still there," he said. "It had 25 to 30 stalls. My grandmother was ambitious."

Sherry Grindeland: 206-515-5633 or sgrindeland@seattletimes.com

Colman diaries![]()

![]()

The diaries of Clarissa Colman have been copied digitally and are available for research purposes through the Eastside Heritage Center in Bellevue. The originals will be on display at the Winters House, 2102 Bellevue Way S.E. in Bellevue this fall. Dates will be announced at www.eastsideheritagecenter.org/. For information, call 425-450-1049.