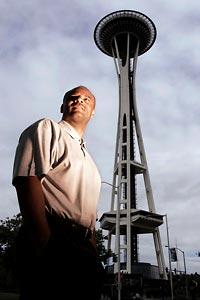

The man that is Moon

His phone blinked. Incoming call. It came from the folks at the Pro Football Hall of Fame, welcoming him, first ballot, validating him, first opportunity.

At last, Warren Moon felt like he belonged.

Now how would he react after everything he went through? The racism. The sojourn into Canada. The arrest. The five professional football teams, in two leagues, in two countries — 49 years building to this moment.

"Everything came pouring out of me," he says.

The entirety came flooding back, consuming him with memories from Pop Warner to the present. Mimicking the wipers sweeping snow off the windshield of his rental car, he cleared tears out of his eyes with both hands.

His journey down memory lane started there, appropriately, behind the wheel of a rental car bound for downtown Detroit last February at the Super Bowl. And continued, for the last six months, as Moon has retraced his life to invite 500 people (at least 300 are confirmed) to Canton, Ohio, next weekend and boil all those memories into eight minutes allotted for his speech.

This is what the pinnacle earns a guy like Warren Moon. Six months to relive memories. Eight minutes to tell his story.

Man of the house

Start with mom, growing up. He was a stubborn boy who roamed Baldwin Hills Park in Los Angeles and took the top off his mother's empty wine bottle to emcee for six sisters, imitating The Supremes and The Jackson 5.

"They were pretty good," Pat Moon says. "I wish now I had recorded them."

His mother and sisters taught Moon everything but sports, taught him how to sew, how to press clothes, how to bake cookies every Thursday to relax before football games. Taught him to be neat and clean, the only guy longtime friend Lorenzo Romar knows who comes back from a road trip, stops at a store for window cleaner and just starts cleaning.

Moon grew big and strong and fiercely protective as the years went by. No longer the skinny boy whose mother brought him to the office of Hamilton High's football coach.

Jack Epstein remembers that day. The dapper, perfectly pressed suit the 10th-grader wore to class. The way the school's makeup — white, Jewish, affluent — didn't seem to bother him.

The coach watched Moon closely, making sure the boy fit this strange environment — and it fit him. More than 30 years later, those eyes remember, clear as the day it happened. At one B game, the backup quarterback shot the football 50 yards in the air — this "little, itty, bitty guy" who threw so hard Epstein swears he saw steam coming off the ball.

"Next year," Epstein told Moon that afternoon, "you're our starting quarterback."

They went together to West Los Angeles Junior College after Division I schools balked at a black man playing quarterback, wanted Moon to play anywhere but there. Epstein knew better, and Moon trusted him like a father.

Moon lost his own father at age 7 to heart and liver ailments, became the man of the house soon after. He once told Tiger Woods' late father he envied their relationship, the one he never had. Pat Moon remembers her son took the responsibility seriously, repeated it all the time.

"I'm the man of the house."

Hence Moon's first nickname: Daddy Warren.

Death threats and taunts

Clyde Walker had a brown Ford Falcon. Warren Moon needed a ride. And they have rolled together since high school, paving memory lane — Moon playing deejay to Walker's driver, and playing keyboard on the dashboard.

Walker was there for the death threats before a game against Crenshaw High — and the five touchdowns Moon threw as he shrugged them off. And the high-school all-star game Moon wasn't invited to that they watched together, in silence, from the stands.

"People just had no sense of what he was capable of," Walker says. "Just like at UW."

They lived together at the University of Washington in an apartment on Bellevue Avenue on Capitol Hill. Entertained high-profile recruits such as Dave Henderson and Ronnie Lott. Endured two seasons' worth of boos and racism from restless fans unimpressed with new coach Don James and the black man playing quarterback.

Moon has relived this part of his past many times before, and poignant memories poured out on his journey back. The hardest part: looking at 10 sets of eyes in the huddle, searching him, waiting for Moon to react, wondering how he would. The next-hardest part: the cacophony of boos.

James called Moon into his office early on, told him the coaching staff logged everything, every pass, every completion, every play in practice. Moon always graded better than the others. He would remain Washington's starting quarterback.

Moon pretended the whole mess didn't bother him, but Thelma Payne knew better.

He met Thelma and her husband Willie through another roommate, Leon Garrett, at UW and later asked them to be his godparents. Willie became the father he never knew. Their home became a haven for him, a refuge, a place to eat and laugh and, early on, forget and cry — "almost like being in another country," Moon says.

Thelma could tell when things were bad. He was so tense, like a can of soda shaken and about to burst. She would sit him on the couch, place his head on her lap, force him to breathe deeply and think about the ocean, the beach, anything relaxing.

"It pained me," she says now. "I get tears just talking about it."

Walker put up with racist slurs bandied around the stands, listened to fans question his friend's intelligence, until he could take no more. Then he stood up, started talking back, and only narrowly avoided several fights.

"It was tough to listen to the ignorance, to listen to the racism, to listen to the frustration a lot of fans were feeling," Walker says, sipping coffee near his home near Lake Sammamish. "They didn't get it. I felt sorry for some of those people."

They feel sorry, too. People have approached Moon in the years since he led the Huskies out of obscurity and to a 1978 Rose Bowl victory, grown men, bawling, asking for forgiveness.

"Those were some bittersweet days," Moon says. "I learned a lot about people. I learned about how tough I was. And I learned a lot about adversity and success."

You've got a friend in me

Romar and Moon still cringe at the outfits they wore when they met at a party in 1978. Big, wide collars. Wild patterns. Black leather coats. Moon sometimes laughs at the memory of the basketball-sized afro sprouting out of Romar's head. He's also reminded often of his own 'do, like at Chiefs tight end Tony Gonzalez's Fourth of July party this year, where a picture of Moon with big hair hung over the bar, DOOFUS scrawled underneath.

Moon and Romar became inseparable, watching every game in town they could get their eyes on. Romar watched Moon, too, the way he mixed easily with businessmen, boosters, athletes, anybody he came in contact with.

Always cool. Always calm. Especially on Romar's wedding day.

It did not start well. Romar went across town to pick up his tuxedo at 10 a.m., and the pants did not fit. En route to another store, he hit gridlock, and didn't return to his mother's house until close to 1 p.m. — when the wedding was scheduled to start.

There sat Moon in the kitchen, not dressed, either.

"Relax, man," Moon said. "Weddings never start on time."

Years later, Moon urged Romar to take the job as UW basketball coach, then put in a call to athletic director Barbara Hedges. This did not surprise Romar.

That was Moon. Daddy Warren. Oblivious to pressure. Even when NFL teams balked at the same thing colleges did — a black man under center. The misconception, agent Leigh Steinberg says, is that Moon would not have been drafted by the NFL. He probably would have been a third- or fourth-round pick, but teams still wanted him to switch positions. Anywhere but there.

So Moon packed up, and drove north to defy convention once more.

Next stop: Canada.

He brought his mom, bought her a fur coat and went to Edmonton, Alberta. He played five seasons there, won five Grey Cups, passed for more than 20,000 yards. He found another coach, Hugh Campbell, who believed in him. And something else, something even more important: acceptance.

"I was only judged on the field," Moon says. "Those were some of the best days of my football career. Because we were winning."

Moon was inducted into the Canadian Football Hall of Fame in 2001. The Paynes were supposed to go then, but Thelma fell ill and was hospitalized. Moon threw Willie a retirement party in 1998, stood up and spoke and cried like a newborn baby. Willie has some health issues of his own now. That's why the trip to Canton means so much.

"That was one thing that he has lived for," Thelma says. "To see Warren go into the Hall of Fame."

Help me help you

They met. And met. And met again. Steinberg calls it the longest courtship in the history of agent-client relations, "the longest investigation anyone has ever faced who wasn't confirmed for secretary of state or defense." Moon met or called Steinberg at least 35 times, talked to everyone who met him — sportswriters, family, friends.

Steinberg started to understand Moon then — so thorough, so meticulous.

Moon and Steinberg balanced each other out. Steinberg liked the way Moon carried himself — so stoic, so involved, the pillar, the rock. Hence Steinberg's nickname for his longest-standing client: Yoda. Moon liked Steinberg's background — progressive, forward-thinking parents, student-body president at Cal back when students rallied at Haight-Ashbury Park — the way he wore his emotions outward, yin to Yoda's yang.

"I've always seen him as someone who could be President of the United States, CEO of a major corporation, broadcaster," Steinberg says, sitting in his Newport Beach, Calif., office. "There is no limit on how gifted he is."

And no limit on how much money they could make each other. Especially in 1984.

Looking to leave Canada for the NFL, they took a secret visit to Houston in the middle of the night, went to the Oilers facility when no one was around, ate dinner at an obscure downtown restaurant.

Seven teams were interested in Moon. Houston owner Bud Adams promised oil fields. New Orleans took the duo on a boat, pointed at the skyline and said, "All this can be yours." They arrived in New York City at 5 a.m., trash strewn in the streets, two cab drivers fighting on the curb.

The headline the next day in a New York tabloid read: Spaced-out Giants Shoot for the Moon.

They narrowed the list to two teams: Houston and Seattle. Both teams offered $5.5 million for five years, the largest contract in NFL history at the time. Only Houston offered $4.5 million as a signing bonus, the Seahawks only $1.1 million. Houston hired Hugh Campbell, Moon's coach in Edmonton, at the last minute.

To this day, Moon swears he wanted to sign with the Seahawks. But $4.5 million guaranteed was too much to pass up.

Moon thought, maybe, he could play in the NFL at least as long as he did in Canada. He played much longer — with the Oilers, the Minnesota Vikings, the Seahawks and the Kansas City Chiefs. He retired in 2000 with more than 49,000 NFL passing yards and more than 70,000 overall — 40 miles' worth. He also threw 435 touchdowns in both leagues and made nine Pro Bowls in the NFL.

Steinberg and Moon went through it all together. The highs: Steinberg rising to become one of the top sports agents in the world, representing 60 first-round NFL draft picks and a record eight No. 1 overall picks. Moon rising to become one America's most recognizable athletes. The business, Leigh Steinberg Enterprises, they built together and now partner in.

Moon even loaned Steinberg the money to buy his first house. And they talked so much on the phone that Pac Bell used that for a television commercial.

The lows: Moon's highly publicized arrest for a domestic incident in 1995. Steinberg's highly publicized drinking problems and lawsuit involving former employees splitting from his company. And neither will forget the Buffalo playoff game in 1993, where the Bills stormed back from a 35-3 deficit to beat the Oilers. Moon says that game plays endlessly on ESPN Classic. He only watches the first half.

"Talk about adversity," Steinberg says, laughing. "That one game would take 20 years off anybody's life."

Steinberg was there for Moon the last time he lost his emotions in a rental car. It happened at another Super Bowl, although in 2000, the circumstances were much different.

His first marriage was all but over.

This was after nearly 20 years of marriage to the former Felicia Moon, whom he met in high school, and five years after one of Moon's children called 911 to report a domestic dispute between his parents.

Steinberg was sitting in the hot tub at Patriots owner Robert Kraft's house, watching ESPN laud him for the biggest week ever by an agent, when he got the call.

"That was the lowest of low points in the last 30 years," Steinberg says.

Felicia, shown in pictures with deep bruising around her neck, was forced to testify in a Texas courtroom. A jury eventually acquitted Moon of assault charges. But the man once billed as the ultimate role model, the ultimate family guy, will always have this blemish on his legacy. He expresses regret over "exposing my kids" — Chelsea, Jeffrey, Blair and Joshua — "for them having to go through it and deal with it."

Moon says he and Felicia are still close, still friends, that they still talk, that she will be in Canton with her new husband. He says he even contemplated having her present him at the Hall of Fame. ("How weird would that be?" Moon says.)

"We started dating when I was in high school," Moon says, "when I was nobody. All the crap I went through, she was right there with me. She's as much a part of my success as anybody."

Out of respect for his current wife Mandy — Moon remarried in 2005 after dating her for four years — he chose Steinberg to speak instead.

Reaching the pinnacle

Hours after Moon took that phone call last February, he rolled into Steinberg's annual Super Bowl party with Troy Aikman, a fellow inductee. Steinberg was sitting down when Moon walked in. He needed to be for the avalanche of tears that followed.

"It was like all those years, and everything that we went through, and all the roads we traveled, it culminated in one moment," Steinberg says.

They will gather next weekend in Canton, Ohio, at least 300 strong. Pat Moon. Jack Epstein. Clyde Walker. Thelma and Willie Payne. Lorenzo Romar. Leigh Steinberg. Moon's family. Former teammates, coaches, trainers and executives from the NFL and CFL.

And people from the Crescent Moon Foundation, which has given out hundreds of college scholarships since Moon started it in 1989. He also runs an annual celebrity bowling tournament in Las Vegas and a Seattle-area golf tournament with weatherman Steve Pool that benefits Children's Hospital.

Moon thought of all of them the past six months. Eight minutes? For all that?

Moon barely has time to think about it. There's a book about the Field Generals, a group of African-American quarterbacks — Moon will be the first inducted into the Hall of Fame — coming out. There are autograph shows for the man whose signature is worth five times more than it was last January (about $150 now). There was the Seafair parade on Saturday, in which Moon was the grand marshal.

Plus, Moon says he will sign a three-year deal with the Seahawks sometime this summer to continue broadcasting and expand into a goodwill ambassador/spokesman for the team.

This past week, Moon went to Hawaii. Three days without distractions. Three days to write his speech. Eight minutes. For all that.

"No matter what people debate about me from here on out," Moon says, "no matter what people say, good or bad, they can't ever take this part away from me. They can say I wasn't good enough. They can say I didn't win a Super Bowl. But I'm in the Hall of Fame. So what else can you say to me? So what? I'm in the Hall of Fame."

And at last, Moon belongs. There at quarterback.

Greg Bishop: 206-464-3191 or gbishop@seattletimes.com

| NFL statistics | |||||||

| Year | Team | G | PA | PC | Yds. | TDs | Int. |

| 1984 | Houston | 16 | 450 | 259 | 3,338 | 12 | 14 |

| 1985 | Houston | 14 | 377 | 200 | 2,709 | 15 | 19 |

| 1986 | Houston | 15 | 488 | 256 | 3,489 | 13 | 26 |

| 1987 | Houston | 12 | 368 | 184 | 2,806 | 21 | 18 |

| 1988 | Houston | 11 | 294 | 160 | 2,327 | 17 | 8 |

| 1989 | Houston | 16 | 464 | 280 | 3,631 | 23 | 14 |

| 1990 | Houston | 15 | 584 | 362 | 4,689 | 33 | 13 |

| 1991 | Houston | 16 | 655 | 404 | 4,690 | 23 | 21 |

| 1992 | Houston | 11 | 346 | 224 | 2,521 | 18 | 12 |

| 1993 | Houston | 15 | 520 | 303 | 3,485 | 21 | 21 |

| 1994 | Minnesota | 15 | 601 | 371 | 4,264 | 18 | 19 |

| 1995 | Minnesota | 16 | 606 | 377 | 4,228 | 33 | 14 |

| 1996 | Minnesota | 8 | 247 | 134 | 1,610 | 7 | 9 |

| 1997 | Seattle | 15 | 528 | 313 | 3,678 | 25 | 16 |

| 1998 | Seattle | 10 | 258 | 145 | 1,632 | 11 | 8 |

| 1999 | Kansas City | 1 | 3 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| 2000 | Kansas City | 2 | 34 | 15 | 208 | 1 | 1 |

The Moon file![]()

![]()

Position: Quarterback.

Ht.: 6-3. Wt.: 212.

Born: Nov. 18, 1956 in Los Angeles.

High school: Alexander Hamilton (Los Angeles).

Colleges: West Los Angeles Junior College and the University of Washington.

College highlights: Passed for 3,277 yards with 19 touchdowns as a three-year starter for the Huskies after transferring from West Los Angeles JC ... Was MVP of the 1978 Rose Bowl, leading a 27-20 upset of Michigan, hitting on 12 of 23 passes for 188 yards and two TDs.

Pro highlights: Began pro career with CFL's Edmonton Eskimos (1978-1983), winning five straight Grey Cups ... Signed with NFL's Houston Oilers as an unrestricted free agent in 1984 ... In NFL career, completed 3,988 of 6,823 passes for 49,325 yards, 291 touchdowns and 233 interceptions ... At retirement, his pass attempts, completions, passing yardage and total offense totals all ranked third all-time. His TD total was fourth ... His nine 3,000-yard passing seasons was third in league history ... His number of 300-yard passing games — 49 — are third in the NFL behind Hall of Famers Dan Marino (60) and Dan Fouts (51) ... Recorded a then-record nine 300-yard games in 1990, including a 527-yard effort at Kansas City, second-most in NFL history ... Holds record for quarterbacks with eight straight Pro Bowl selections (1988-1995 seasons) and added a ninth following the 1997 season ... Signed as a free agent in 1997 with the Seahawks, where he set franchise records for completions (313) and passing yards (3,678).