Playing for Fun and Profit

EVERY WEEK, a bunch of friends (who happen to slightly resemble the cast of "Friends") gather in Lincoln Davis' cool bachelor apartment with its abstract paintings, view of the Space Needle and blue leather couch. Usually, they watch the drama "Lost." But if it's a rerun, as it often is, they skip TV to play board games. Their favorite is Cranium.

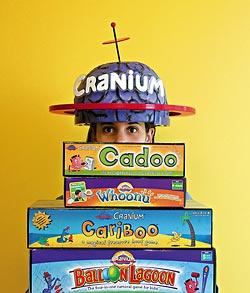

Developed eight years ago by two Microsoft stars who quit to become entrepreneurs, Cranium blends elements of Pictionary and Trivial Pursuit with word puzzles, sculpting, humming and charades. Cranium has won the Toy Industry Association's Toy-of-the-Year game award four out of the past five years, and along with a dozen sibling titles, has sold more than 15 million games in 10 languages and 30 countries. The privately held company won't reveal its actual revenue, but compares itself to Pyramid Breweries, which last year reported $50 million in sales. In the toy industry overall, unit sales are down 6 percent; for Cranium, unit sales are up 50 percent.

So are Cranium marriage proposals. The company knows of six guys who proposed using the Cranium game, several of them requesting, and receiving, customized game cards.

"S_M_NTH_W_L_ _O_ M_R_Y _E?" read the card special ordered in February by 20-year-old James Bates, of Tennessee, who gets multitasking bonus points for watching the Super Bowl while playing Cranium and popping one of life's most important questions. "There was hugging," he says, "and then we went on and played a couple more games."

Cranium is not just a lucky smorgasbord that happened to hit it big. Underneath the purple sculpting clay and wacky questions, there's a philosophy ("Everyone Can Shine"), the theories of intelligence developed by Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner, and an unlikely confluence of '90s venture capital, Dilbert cubicle backlash, and a couple of dads burned out on playing Candyland.

"What Cranium did was it rewrote the rules," says Chris Byrne, aka The Toy Guy, who reviews toys for www.toyguy.com and other media. "Where board games fit into the adult world is their ability to foster communication and interaction. . . . We're on the Internet, Blackberries, cell phones. But what's our face time? There's a warmth, a lightness from the interpersonal interaction that comes from Cranium. People are hungry for that kind of connectedness."

At the moment, in the bachelor apartment, something weird is going on. The card in play calls for someone from each team to act out silent clues, like charades.

One of Lincoln's friends, a tall, skinny guy in a baseball cap, puts his hands together as if in prayer. Another alternates reading from an imaginary book while knocking on a pretend door. The third guy jumps onto the blue leather couch and appears to do sets of rather provocative push-ups.

"Pray!" someone yells. "Priest!" "Archdiocese!"

No, no, no, the actors shake their heads and keep praying, knocking, humping.

Meanwhile, as sand streams through the timer, the guessing goes wild.

This is a Cranium Moment. Dating yupsters interacting with each other, laughing, bonding, high-fiving on an otherwise humdrum weekday night.

It's exactly what Richard Tait and Whit Alexander had in mind as they set out to make a better board game.

CRANIUM HEADQUARTERS sprawls over two floors in an unremarkable building on First Avenue, not far from the Pike Place Market. Dilbert would not recognize the place. The rooms are painted lime green, sunflower yellow, tomato red, aquarium blue, accented with purple brains and designed to look, from above, like a Cranium game board.

The corner offices, with stunning views of Elliott Bay, are not reserved for the chief executives, but instead open to all employees as brownbag lounges and meeting rooms. The staff (about 100 including several in the United Kingdom and China) is young and hip: plastic retro eyewear, funky jewelry, groomed eyebrows. Their business cards sport fun titles: Head of the Hive (creates a buzz about products), Keeper of the Flame (publishing), Chief Cultural Attaché (international division), Concierge (receptionist), Chief Culture Keeper (human resources), Edgar Allen P.O. (purchasing).

Founders Tait and Alexander are, respectively, Grand Poo Bah and Chief Noodler. "We're yin and yang — I love that our personalities blend," Tait says, describing each of their strengths in Cranium parlance. "I'm star performer and creative cat. He's datahead and word worm. If there's a problem, my solution is Powerpoint. His is Access. We think in different applications."

Tait's office is dominated by gumball machines, wind-up toys, brains in every shape and size, autographed sneakers of Michael Jordan, John Stockton, Karl Malone.

At 42, the Grand Poo Bah is spry and stylish. He has wild red tresses, a soul patch, a Nike cuff watch, an iTunes library with 47,000 songs, a wife and three young children, a touch of brogue from the Scottish homeland he left when he was 21. Every morning, first thing in the office, he phones Scotland to chat with mum.

From his mother, Tait inherited a love for family togetherness; from his father, a pioneering spirit. "In Scotland, you do what your parents have done before you," Tait says. For generations, his relatives had served the Templeton family, his grandfather as a chauffeur. Tait's father was expected to become a household servant, but instead went his own way, eventually running the largest Polaroid manufacturing plant in Europe.

Early on, Tait was an entrepreneur, his mom constantly fielding phone calls from the parents of schoolboys who'd traded away their best Matchbox car for something Tait knew they wanted more.

On his paper route, the aroma of bacon fired his imagination. People buried in their newspapers, chomping on hot pastries called bacon butties. A Sunday Morning Moment. Why not deliver fresh bacon butties along with the newspaper? The idea was so successful, he hired other boys to help him with an expanded route.

After earning a computer-science degree at Edinburgh's Heriot-Watt University, Tait went to business school at Dartmouth, and from there, straight to Microsoft, where Bill Gates selected him employee of the year in 1994. Tait resigned in 1997 after a decade with the company. Remember the late-'90s dot-com frenzy? Venture capital swirled in the air. Tait itched to strike out on his own.

What to do? For weeks, he pondered, sometimes padding around all day in his pajamas, dressing only before his wife, Karen, came home from work.

Then, in what has become Cranium legend, he and Karen spent a rainy weekend playing board games with friends in the Hamptons. When it comes to Pictionary, the Taits have a psychic connection; he scribbles a squiggle, she yells, "MOUNT RUSHMORE!" Of course, they cleaned up. On to Scrabble. The other couple was so good, they'd posted previous high scores on their fridge. Again, no contest. Not much fun.

On the plane back, Tait thought: Why not make a game where everyone can shine? Where everyone can demonstrate their special talent and seem smart and funny in front of family and friends instead of feeling like an idiot?When Tait proposed the business idea to his Microsoft buddy, Alexander's first reaction: "You gotta be kidding. YOU can call my dad and tell him I left Microsoft to make a board game."

His next reaction: Research the idea on the Web.

THE CHIEF NOODLER typed "right brain" and "left brain" into a search engine and came across the theory of multiple intelligences by Harvard's Howard Gardner, a brain scientist who studies stroke victims and the minds of young children. Gardner critiqued the common 20th-century notion of a single human intelligence that can be assessed by standard instruments such as IQ tests.

"A person may be skilled in acquiring foreign languages, yet be unable to find her way around an unfamiliar environment or learn a new song or figure out who occupies a position of power in a crowd of strangers," Gardner writes in "Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century."

Gardner outlines seven intelligences, somewhat simplified here:

Linguistic: The ability to learn and use language to accomplish certain goals. Think lawyers, speakers, writers, poets.

Logical-mathematical: A capacity to analyze problems logically and investigate issues scientifically: Mathematicians, logicians and scientists.

Musical: Skill in performance, composition, appreciation of musical patterns.

Bodily kinesthetic: The potential to use the body or parts of it (like the hand) to solve problems or fashion products. Dancers, athletes, craftspeople, surgeons, bench-top scientists.

Spatial: The ability to recognize and manipulate patterns of wide space as well as more confined areas. Navigators, pilots, sculptors, surgeons, chess players, graphic artists, architects.

Interpersonal: A capacity to understand the intentions, motivations and desires of other people and consequently to work effectively with others. Salespeople, teachers, clinicians, religious and political leaders, actors.

Intrapersonal: The capacity to understand oneself, and to use such information effectively in regulating one's own life.

For Alexander, "I knew that it was a great framework to build this promise that everyone could shine."

He came up with a list of 30 careers that would exemplify each intelligence and then asked, What do these people care about? That generated 40 or so topics: child care, engines and autos, cuisine and gardening, in addition to more predictable literature and entertainment.

He ran all this by Tait, who responded: Jesus, Whit. It's a GAME. It's gotta be fun!

"I thought Richard's point was valid," Alexander says. "I had stumbled on half the equation. Where was the fun part?" How to turn categories into a game?

Being a research-focused guy, Alexander headed to Seattle Central Library: "Let's look back at the ways people have been having fun for the past 150 years." Prowling the stacks, he found three shelves of game books going back that far. He noticed a marked drop-off in games literature in the 1950s (rise of television) and again in the '80s (advent of cable). The era of 19th-century parlor games was particularly rich. Word teasers. Eccentric sporting events. Barnyard-animal impersonations.

"The criterion was we had to be able to take lots of different subject material and map it onto this activity," Alexander says.

In the end, the original Cranium cooked up 14 activities — calling on players to sculpt tacos out of purple clay, spell "confetti" backwards, hum Elton John's "Rocket Man," determine whether humans and giraffes have the same number of vertebrae in their necks. (Yes.)

They knew it was working when volunteer play-testers tried to abscond with the prototype.

They'd developed it in only six months, phenomenally fast by industry standards. Game in hand, Tait and Alexander set out to sell Cranium in specialty toy stores in Seattle, Portland and Vancouver, B.C. It was June. Quickly, they learned they'd missed the industry's annual Toy Fair in February, when retailers decide how to spend their budgets and allot shelf space for the year.

"Toy Fair?" Clueless.

Commiserating over coffee in Starbucks, they looked around and saw their target customers. A Brilliant Marketing Moment.

Coincidentally, Tait had recently met an investment banker for Starbucks while climbing Mount Kilimanjaro to raise money for the anti-poverty agency CARE. Through the banker, they floated the idea of selling the game in Starbucks' cafes. Turns out Cranium was a perfect fit with Starbucks' hang-out-on-the-piazza, coffee-culture brand. Next, Cranium partnered with Amazon.com and Barnes and Noble, booksellers that had never sold games before.

Untraditional, but it worked. In its first year, Cranium sold more games than both Pictionary and Trivial Pursuit in their first years. Eight years later, the company has 100 employees, an infusion of $15 million in investment capital and two dozen more games, books and toys set to debut.

THERE ARE TWO major differences between Cranium games and other games.

"Classic games, from the beginning of time, there's a winner and a loser," says Reyne Rice, a trend specialist with the Toy Industry Association. Think of checkers, chess, your gloating tycoon sister who always dominated Monopoly.

"With Cranium, even though one team wins, everyone feels like they won because everyone got a chance to do something fun, to be good at something," Rice says. "If you've ever had a bad game experience, felt inferior, you appreciate that."

The other difference begins at a game's conception. At Cranium, unlike other large toy companies, games are conceived not to fill a market niche but to create special moments: The Playdate Moment, The Backyard Fun Moment, The Stuck in Your Plane Seat Moment.

Then comes the Moment of Truth. Behind the purple velvet curtain at Cranium headquarters hides a play-test room with red walls and one-way windows where the Wizard of Aha!s (game developer) watches carefully for laughter, confusion, broken parts.

Take Wacky Words, a fill-in-the-blank game reminiscent of Mad Libs, scheduled for release this fall. The first version revolved around a deck of cards with words (hot buttered popcorn, porcupines, baby bottle) players had to use to fill in the blanks. Dud cards prompted apologies: "Mine's not very funny; it's all that I had in my hand." Word wizards had no opportunity to rev their creativity. So the developers replaced the cards with a spinner to indicate the first letter of a word, letting players take it from there.

"Rigatoni, a winter sport, played on a court of ravioli." Twelve-year-old Ben Jaffe and his 11-year-old sister Mimi play-test Wacky Words after an interminably long time puzzling over the prototype's directions with their parents and two friends. But once in the groove, they're giggling ". . . wears cheap perfume and tosses leafy bras! . . . Baby cupids wear linguini and throw insults!" If you're not a tween, you may not get the joke. That's OK. To each, his own silliness.

For Cranium, helping players create their own moments is key. To trigger memories and laughs, Cranium uses emotional touchstones. Songs mom used to sing when you were little. Flip-flops. Superbowl Sunday. Beanbag chairs. No matter if you love or hate it, a touchstone should resonate.

Yet what's culturally powerful for Americans may fall flat in The Netherlands. Instead of merely translating its games, Cranium uses local researchers to identify indigenous touchstones. Australians draw the "rough end of the pineapple" (a raw deal); Spanish speakers sculpt chocolate con churros (hot chocolate with doughnuts).

"So far, we haven't found a completely different sense of humor" across cultures, says Chief Cultural Attaché Molly Kertzer. Bachelor party resonates in all cultures. Surprisingly, so does mullet hairstyle. Bad Hair Day, a charade, is included in every version except the French.

Touchstones even work with preliterate preschoolers. Little kids love to move, and they get a charge out of monkeys, broccoli, trumpets, ice-cream cones, guitars and elephants, so Cranium stamped these icons onto colorful Twister-like pads and added a voice-box that shouts directions: "Spin to a triangle! Put your elbow on an animal!" Hullabaloo's goal was to create a perfect playdate where mom wouldn't need to referee or endlessly pore over fine-print directions.

The first problem, during play-tests, was the disappointed droop on kids' faces when the 15-minute game ended — leaving only one winner. Developers shortened rounds, creating a winner every couple minutes. Prototype problem No. 2: Kids shoved each other off pads à la musical chairs. Easy remedy: Change rules to allow kids to cooperatively cling to each other.

Hullabaloo was named Toy of the Year by the Toy Industry Association in 2003 and 2006. But perhaps the greatest testimony comes from Celeste Welch, mother of Brooke, 8, Courtney, 6, Natalie, 3, and 2-year-old Valerie. Last year, Valerie was diagnosed with a brain tumor. "You initially go through shock," Welch recalls. "You forget what's fun. My husband kept asking me: What did we do for fun?" They took out Cranium's Cariboo, the only game all the girls could play together, then added Hullabaloo and Balloon Lagoon. "Even in the midst of the new tragedy, the girls were always laughing and smiling," Welch says. "They never went through a time of crying or confusion. Really, it's our faith in God that's getting us through. But the Cranium games kept that laughter in the house."

MEANWHILE, BACK on the blue leather couch, the risqué gyrations continue. The other players are laughing so hard they forget to act out the charade. Guesses fly.

"Date?" "Trying to get lucky?" "Fall from grace?"

Time's up.

"MISSIONARY!"

Groans. Giggles. Screams. "I can't believe you didn't get it!"

Nobody won. Nobody cares.

For the yupsters rolling on the floor in laughter, the moment feels completely spontaneous. For the Grand Poo Bah and Chief Noodler, it was totally engineered.

Paula Bock is a Pacific Northwest magazine staff writer. She can be reached at pbock@seattletimes.com. Ken Lambert is a Seattle Times staff photographer.