A Life Of Structure

ARCHITECT KEITH Kolb mentored scores of designers in his nearly 40 years of teaching at the University of Washington's architecture department. His fellow faculty included, at times, Victor Steinbrueck, Wendell Lovett, Norman Johnston, Fred Bassetti and Ibsen Nelsen. Among his many well-known students were Jim Olson and Rick Sundberg, of Olson Sundberg Kundig Allen Architects, and George Suyama, of Suyama Peterson Deguchi.

After serving in the Army in World War II, Kolb earned an engineering degree from Rutgers University, an architecture degree at UW and a master of architecture degree from Harvard. He apprenticed in Cambridge, Mass., at The Architects Collaborative with Walter Gropius, founder of Germany's Bauhaus school, then started his own firm and a teaching career in Seattle.

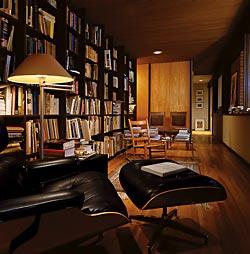

Kolb, 84, is now a UW professor emeritus and a member of the American Institute of Architects College of Fellows. He is retired from active practice. We spoke with him recently in the four-bedroom Laurelhurst home he shares with his wife, Jacqueline.

Q: You built your house in 1960. What was your aim, and how has it worked out?

A: I built this house for my family. In this vicinity, there is a particular light, particular foliage, storms passing in winter, rain. You can see I designed this house to function as a big umbrella: We can go out on the sheltered terrace and enjoy the rain in mild weather. My wife and I have lived in it so long now, yet we both think it works better and better.

Q: The extensive use of glass stands out.

A: These windows on the main floor are 16 feet high. I built this way for the light, and because of the trees across the street. I loved the trees, although some might think they cut into the view. We look straight east toward Lake Washington.

Q: Have your ideas about what makes a good house changed since you designed this one?

A: Naturally, you work with the technology of the time, but no, my ideas remain pretty much the same. Most important in my design principles is the quality of aesthetics. Make the aesthetic work with the client's needs and the work has integrity. You actually can see in a structure the empathy the architect has in observing. It's part of the truth of the way the whole thing is put together.

Q: Is that one definition of a modernist?

A: I guess that's true. Of course, the ancients did the same thing — the Egyptians, the Greeks. This idea that the structure is the architecture is really an old idea; a real modernist will do that. I deplore what we moderns call eclecticism — people copying styles. We live today; we ought to be who we are today, not try to pretend we are Tudor-Gothic or Renaissance-classical or Georgian-some-damn-thing.

Q: Is there anything about your house that you would change today?

A: Insulating glass. I had the option to do that then, but didn't have the money. I figured out in 1960 that I could heat the house for 30 years for the cost of the insulating glass. Q: What drew you to architecture?

A: I was very much involved with music all through high school in Billings, Mont. I had my own dance band, starting at age 12. I was thinking about being a concert pianist, or maybe a composer or conductor, but it didn't seem practical. I was good at mathematics and liked to draw. Around 1939, I talked to a local architect about where to go to school, and it came down to the University of Washington or Michigan. I chose Seattle, and the architecture faculty here was perfect. The first year I was selected to join Lionel Pries' household; he chose two students from each class in the five-year program to live in his home. So you had the advantage of seeing how an architect worked, and help from older students. Pries was doing Northwest modern work in combination with art from India. He was so far ahead of everyone, hardly anyone knew what he was doing.

Q: What was it like working with Walter Gropius?

A: He selected about 16 of us (from Harvard) to study with him, half foreign students. The man who became head draftsman for Le Corbusier was one of my classmates. A number of European architects came and talked to us. Gropius believed in teamwork, but it was a struggle because of our diverse backgrounds. I argued against this way of teaching, because the best design didn't always win out. But he told me that someday this would be valuable experience for me, and he was right. I thought I'd burned my bridges because of my comments, but he called me after I graduated and asked me to go to work for him. There's where I really learned about collaboration.

Q: In your handout for clients you wrote: "Each building or project declares man's concern for his living, learning and working environment." How, then, should a client go about selecting an architect who can aim that high?

A: You have to have a feeling of trust; it is intuitive.

Q: The architect also chooses?

A: You don't have perfect clients, from an aesthetic point of view, but you work around it. Unfortunately, most clients don't have a clue about what an architect does. We train people to read and write, but not about form and space, art and music. Consequently, most people don't know what they are looking for; they simply want someone to put a building together economically. But my experience is from the architect's point of view, and some clients don't work out. What good architects try to do is build an environment for people to discover life, to discover the beauty of things.

Dean Stahl is a Seattle writer. He can be reached at architectsathome@mac.com. Benjamin Benschneider is a Pacific Northwest magazine staff photographer.