Lost, But Not Forgotten

STEPHANIE FULLERTON walks through icy drizzle to place a vase of fresh flowers at her family's burial plot in a corner of Queen Anne's Mount Pleasant Cemetery. She positions the remembrance just below the markers of her parents, Lynn and Pauline, and just above one recognizing her brother, Michael Frank Fullerton.

His marker reads 1960-1990, but the grave is empty. He went missing in 1986, when he was 26. The family settled on the ending date out of deference to his mother. Seeking resolution and recognition for her vanished son was one of her final wishes before she died in 1990.

"During one of the last moments in her final days, she told me, 'Don't worry about Michael. He is OK,' " recalls Fullerton, wrapped in a black coat and scarf, her face chilled red. "I always thought that at some point that marker would have been raised so something, even a set of teeth, could be placed inside."

While presuming death, Stephanie and her sisters still wonder and wait for answers. When she hears about "human remains" being found, she calls the medical examiner to see if they match Michael. Other families do that for their missing loved ones, too.

She is the cemetery's lone visitor on a weekday morning, alone with the near-20-year-old question. People like her feel lonely with their open-ended mysteries, yet she allows herself a melancholy chuckle. "Maybe Nancy Grace will get interested," she says of the cable-news commentator. "Michael was good-looking."

Families like hers, including those with far fresher cases, can relate to such black humor. They notice all the attention lavished on the famous case of the moment, the case that always seem to involve a young, middle- to upper-class white woman. Families out of the limelight watch those cases pre-empt coverage of Iraq and health care and natural disasters while their cases seem to slide, drift, evaporate.

Outside the headlines and airtime, people go missing every day for every imaginable reason in every sort of circumstance. Some who go missing are mentally impaired. Most go missing on purpose, and many juveniles do so repeatedly. Abduction is rare, but when it happens, the perpetrator usually is an estranged parent or acquaintance.

Many cases resolve themselves quickly. The exceptions often end in tragedy. Sometimes they never end. Sometimes the person is found, but nobody knows it because she or he has been reduced to anonymous bones. The only constant in each case is that the person is not just missing, but missed.

THE WALL-TO-WALL coverage devoted to the tragic case of Alabama teenager Natalee Holloway, the massive hunt for fiancée-with-cold-feet Jennifer Wilbanks, and the spate of search-and-save TV shows like "Without a Trace" can make you forget that missing-person reports relentlessly pile up, one on top of another.

The Seattle Police Department's Missing Persons Unit, staffed by two detectives and a community-service officer, fields more than 2,000 cases a year. King County police handle the same amount. About three-quarters involve juveniles.

The weekend that Holloway went missing in Aruba, the Seattle unit fielded 15 juvenile cases. A 15-year-old girl runs from home. Another 15-year-old girl ditches a county intervention facility (eventually picked up in Des Moines, working as a prostitute). A 17-year-old girl leaves a group home. A 15-year-old boy runs from his parents. And on it goes. All those kids are what police call "frequent flyers," meaning they do it repeatedly. As frustrating as these cases are, authorities must still try to track them down because the kids often run smack into trouble.

"We have to treat those kids as victims," says Seattle Police Detective Tina Drain. "They are not just missing. What they are is vulnerable to predators."

On a typical Tuesday morning, Drain calls the King County Medical Examiner's Office to see if a bone found on shore near Carkeek Park is human. She has at least three disappearance cases that occurred near or on the water. She reviews a report for a repeat runaway, a teenage girl who has disappeared with her boyfriend. Drain believes they went to California, where the girl will work as a prostitute and he, with his long rap sheet, will be her pimp. (A week or two later, they are arrested in Sacramento doing just what Drain predicted.)

Drain and partner Dave Ogard have to make difficult priority judgments. They look at the kid's age, health and circumstance of leaving. How many times has he run before? Is there any indication of imminent danger? Which of these need immediate attention from homicide detectives?

One afternoon, a Seattle teenager did not come home from school, tossing her loving family into a frenzy. The 16-year-old was a good student and had no history of bad behavior. Her mother, father and siblings got busy, calling her friends, driving the neighborhoods. They phoned the school and police.

Washington does not require a 24-hour waiting period before police will take a report. The longer the wait, the colder the trail. In those cases of abduction that wind up in death, the killing is done in a matter of hours.

In this case, it turned out that their daughter and another girl had made a suicide pact, but the second girl got sick from downing pills and was taken to the hospital, where Ogard interviewed her. She told Ogard where her friend would be, and he relayed the information to the family, who beat the police to the site and picked up their daughter, safe.

"As a parent," the mother says, "the worst part is that ugly feeling of not being able to do anything. You feel that emptiness when someone you love so deeply is gone. Of course we worried she had been taken or killed. Then when we heard she was planning suicide, that was a slap in the face. We were asking ourselves, 'What did we do?' She left us a note, that we didn't take as a suicide note at the time, that told us we had nothing to do with her decision, but it was still so hard. You wish your child would know just how much you love them."

For all the false alarms and happy endings, though, there is heartbreak, like the case of 10-year-old Adre'anna Jackson, who vanished from her Lakewood neighborhood about eight weeks ago.

WHEN "RUNAWAY BRIDE" Wilbanks was wasting taxpayer money in several states, Seattle logged six adult missing-person cases, five of which were quickly and quietly solved. Seattle, though, has about 80 open cases, some dating back to the 1970s.

Adults create different challenges. If police find a person who is sane and healthy, they cannot tell the loved ones where he or she is without the person's permission. As with kids, authorities must determine if a case involves imminent danger and vulnerability. Is leaving out of character? Is there any reason for leaving?

Sometimes women go missing to escape domestic violence, and the person reporting is the abuser. While spending a day driving around the city and following up on reports, Drain wound up at a local elementary school. A man had reported his girlfriend and her son missing. Talking to a teacher at the boy's school, Drain learned that the woman was living in a shelter and kept her developmentally disabled son away from school so the boyfriend couldn't track them down.

Janet Rhodes, who works missing-persons reports for King County police, recently located a man who disappeared in early 2003. Family members said he had talked of "ending it." As the case lagged, an attorney advised the family to seek a presumptive death certificate so they could work out financial troubles. But Rhodes kept after it and found the man in Los Angeles through a lead in Alaska. He said he wanted no contact with his family. Rhodes told the family he was alive and well. Suddenly, some weeks later, he reunited with his family.

Presumptions can be dangerous because people are unpredictable. In one King County case, a single woman vanished, leaving food cooking on the stove and a number of hungry cats. It had all the markings of an abduction, but several months later she was found living in the Midwest. She said she just needed a change.

A woman called Seattle Police to report that her adult daughter, who tried to commit suicide last summer, was missing. Drain persuaded the mother to unfreeze the bank account the mother and daughter held jointly. When the mother did that, Drain learned the daughter checked into a downtown Portland hotel. Portland police found the woman just after she had taken large amounts of oxycontin and morphine, but were able to get her to a hospital and stabilized.

Death, of course, is a reason for vanishing. Green River Killer Gary Ridgway got a head start because police were slow to connect the initial missing women cases that turned out to be among his victims. Many of the victims had lifestyles that complicated how their disappearances were reported and investigated. When task-force detectives began treating missing women cases as homicides they amassed critical information about the killer's pattern.

Police agencies have been criticized in general for not paying enough attention to missing-person reports. Since joining the unit four years ago, Drain has been part of a statewide effort to improve how cases are handled, from taking faster, more critical looks at whether foul play is involved to patching record-keeping gaps. She was part of the State Attorney General's Missing Persons and Unidentified Remains Task Force and developed a DVD "toolbox" designed to train officers for missing-person investigations.

The volume of these cases overwhelms police, but a family is not interested in the workload — only its loved one.

DR. KATHERINE TAYLOR, forensic anthropologist with the King County Medical Examiner's Office, removes a sealed plastic bag from a small box labeled #90-0485. From the bag, she takes a filthy black-and-white-checked shirt with gaping tears. She pulls out stained light blue pants, waist 36, and torn even worse. Next, a pair of old-fashioned bifocals.

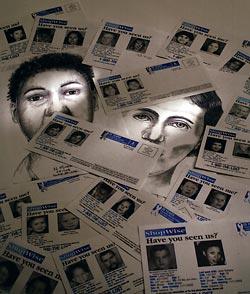

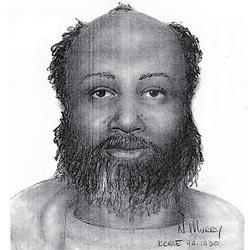

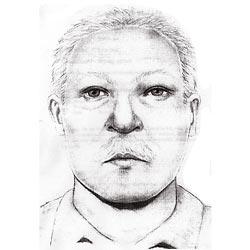

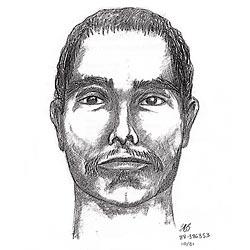

Other than some bones found in a South Seattle transient camp in 1990, there are few other clues. Authorities figure he was 5 foot 8 and probably older than 40. Whoever he is, he is just one of 32 sets of unidentified King County remains listed in a binder of cases dating back to 1984. The man's sketchy case resides next to "Jane Doe 0005," "Mandible On Beach," "Snoqualmie River Bones" and victims yet to be identified in the Green River murders. In one case, the best hope is a tattoo of an eagle flying above a mountain.

Taylor is at the forefront, along with Seattle forensic dentist Gary Bell, of a push in Washington and nationally to do a better job identifying these people. The databases are exhaustive but not adequately updated or in sync.

In fact, many of the cases offer little hope without DNA or dental records. Police are required to file dental records with the Washington State Patrol's Missing and Unidentified Person Unit (MUPU) for missing cases of more than 30 days. If no dental records are located, they must at least file a notice stating that. While Washington appears way ahead of other states, dental records have been filed for only a small percentage of those cases.

The reports are critical, and not just to foster computer matches. The discovery of an African-American man who wore braces found floating in Puget Sound connected with Drain, who recalled taking a report that had a description of such a man. It led to a match. Another person was identified because he wore Birkenstock sandals.

Sometimes, investigators identify someone through luck. Taylor recently studied the remains of a woman found in Peasley Canyon near Auburn. All Taylor had to go on was a cranium and a few bones. The skeletal areas to which her neck muscles attached were large, suggesting a muscular neck. Taylor estimated she was big-boned and between 5 foot 6 and 5 foot 10. MUPU did not furnish a match. Taylor began trolling the North American Missing Persons Network (www.nampn.doenetwork.us). She looked through the Washington list, and when she got to the year 2001, the first picture that popped up was of the woman she imagined. It was Darlene Campos of Lakewood.

"Her mother told me she didn't want to leave her apartment for like a year because she was so sure she was going to call and she didn't want to miss it," says Taylor, who informed her. "I've had mothers say they go to bed every night wondering, does she have her mittens, a roof over her head, is she eating OK, is she lonely? When they get a call from me it isn't very good news, but that cycle can stop and they can start to mourn and move on to the next stage."

Stephanie Fullerton, too, is prepared for any news. She thinks her brother upset a drug dealer, who killed him. Michael lived in West Seattle. His abandoned car was found on Capitol Hill. He went missing, she says, when street gangs and the Green River killer kept police occupied. She thinks his case slipped through the cracks and now, thousands of new cases later, the cracks have deepened into a fissure.

"I'm thinking about holding a gathering when the 20th-anniversary day comes this fall," she says. "I want to make it upbeat if I can. Michael would be really irritated by how much of a problem this has been."

Richard Seven is a Pacific Northwest magazine staff writer. He can be reached at rseven@seattletimes.com. Benjamin Benschneider is a magazine staff photographer.

Call 911 and provide as much information as possible.

Be forthcoming, even if it means revealing unflattering details.

Keep personal items that may provide DNA samples.

Use support agencies like the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children at 1-800-THE LOST; National Center for Missing Adults at 1-800-690-FIND; and Families and Friends of Violent Crime Victims at 1-800-346-7555.

Call the investigating detective to give or get an update.