By Brier Dudley

Seattle Times technology reporter

The Puget Sound region has a surplus of brilliant engineers.

They design airplanes that circle the globe, software that brings computers to life and medicines that ease suffering.

But the region has also had its share of engineering bloopers. The revelation last month that Seattle's monorail tracks are close enough for the cars to sideswipe each other was the latest in a series of embarrassing snafus over the past century.

Sometimes it's hard to blame anyone in particular. Engineering implies precision, but getting things done involves trade-offs — balancing goals and risks with the limitations of materials, budgets, schedules and space.

Things become complicated when politics are involved, as they were with the monorail. Operator error is the official cause of the Nov. 26 collision, but it was an engineering decision in 1988 that put the tracks too close together.

The tracks were rebuilt to accommodate a new shopping center, and the powers that be wanted to minimize their bulk near the center. A city councilman, drawing on a napkin, designed the tapered line, which requires drivers to yield to one another. It worked fine for 17 years.

"The world of engineering is the world where we build things three times stronger than they need to be, then something will happen and they get loaded four times more than they should be, and it breaks," said James Holt, who teaches engineering management at Washington State University. "We try and do the best we can within reason,"

Deadlines are also a factor. Last week Microsoft Vice President Amitabh Srivastava insisted his team will take its time to be sure Vista, the next version of the Windows operating system, is high-quality. But Microsoft has already told customers and Wall Street that Vista will be completed in late 2006.

The team building Seattle's famous Slo-mo-shun hydroplanes perhaps should have been so careful when they were rushing to finish Slo-mo V in time for a race in 1951.

Boatbuilder Anchor Jensen worried that the design would make the boat flighty, according to a history posted at slomoshun.com. Jensen persuaded team owner Stan Sayres to change the design, warning him that "those sponsons are not right," but the boat still went airborne in 1955.

Brier Dudley: 206-515-5687 or bdudley@seattletimes.com

<strong>2) Bus-tunnel tracks</strong><BR>Corners were cut on installing tracks when the downtown transit tunnel was built in 1988, saving less than $1.5 million. Now the tracks are being replaced so that they'll work with light rail, forcing downtown traffic to be rerouted. The project, in addition to the track replacement, includes other work needed to retrofit the tunnel for rail service and will cost $45 million. Managers knew the tracks may not work but didn't inform elected officials. (KEN LAMBERT / THE SEATTLE TIMES)

<strong>1) Monorail collision</strong><BR>A Nov. 26 collision revealed that the monorail tracks are too close together at a spot near Westlake Center. The tight spot was created when the tracks were redesigned in 1988 to accommodate the mall, so the car drivers must yield to each other. (DUSTIN SNIPES / THE SEATTLE TIMES)

<strong>6) Hood Canal Bridge sinks</strong><BR> It was supposed to be impervious, but a windstorm and a strong tide sank the Hood Canal Floating Bridge in 1979. It was rebuilt, then nearly sank again in a 1990 storm when a generator failed. (AP)

<strong>3) Narrows Bridge collapses</strong><BR>The poorly designed Tacoma Narrows Bridge fell into Puget Sound on Nov. 7, 1940. The bridge, known as Galloping Gertie because it was so bouncy, collapsed during a windstorm four months after it opened. It was rebuilt in 1950. (JAMES BASHFORD / AP)

<strong>9) Cathedral dome collapses</strong><BR>The copper-topped dome of St. James Cathedral overlooking downtown Seattle was supposed to be "practically indestructible," according to a church newsletter heralding its construction. But it collapsed under the weight of 15 tons of snow on Feb. 2, 1916. It was replaced with a less-expensive arched ceiling. ( COURTESY OF MUSEUM OF HISTORY & INDUSTRY)

<strong>8) Kingdome tiles fall</strong><BR>Soggy Kingdome ceiling tiles fell in 1994, leading to the cancellation of two Mariners games. Water had seeped through the roof while it was being repaired. It sounds minor in retrospect, but the debacle soured some sports fans on the dome and presaged calls for a new stadium. A few years later, the dome — an engineering marvel — was demolished and replaced with separate football and baseball stadiums costing more than $1 billion. In this photo from July 20, 1994, Kingdome employee Tom Long examines the roof above the 300 level, where ceiling tiles fell onto some seats. (ROD MAR / THE SEATTLE TIMES)

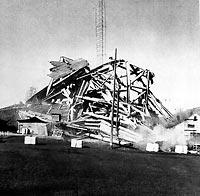

<strong>4) Husky Stadium collapse</strong><BR>Husky Stadium's north grandstand collapsed during construction in 1987. A contractor took the blame, saying it removed guy-wires before key pieces of the roof structure were installed. (AP)

<strong>10) Slo-mo-shun backflips</strong><BR>Seattle's beloved Slo-mo-shun V hydroplane did a complete backflip during a qualifying run for the 1955 Gold Cup on Lake Washington. The builder had worried about the flighty design, but the boat was a champion that won Seattle's first unlimited hydro race in 1951 and the 1954 Gold Cup. After the wreck, Slo-mo V was repaired and raced as Miss Seattle, Berryessa Belle and Miss Tri-Cities. It's now owned by Bruce McCaw. (VIC CONDIOTTY / THE SEATTLE TIMES)

<strong>5) Hammering Man falls</strong><BR>The Hammering Man fell during the sculpture's 1991 installation at Seattle Art Museum. It turned out he was heavier than expected, exceeding a crane sling's weight limit. The only injury was to the Man's pride; he was repaired and erected the next year. (STEVE RINGMAN / THE SEATTLE TIMES)