"A Perfect Pledge": A satisfying familial tale, slightly familiar

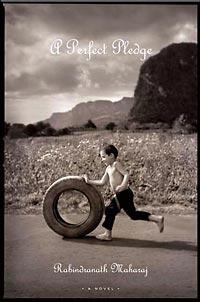

"A Perfect Pledge"

by Rabindranath Maharaj

Farrar, Straus and Giroux,

401 pp., $25

What a delicious feeling it is to read the first pages of a 400-page book and know you are in the hands of an accomplished storyteller.

Literary comparisons are often odious, but it is impossible not to compare Rabindranath Maharaj with Nobel Prize-winning author V.S. Naipaul. Both are Indian Trinidadians by birth, both are émigrés — Naipaul to England and Maharaj to Canada — and both are contemptuous of the Third World in general and Trinidad's reluctance to discipline itself in particular. These commonalties combine to make "A Perfect Pledge" reminiscent of "A House for Mister Biswas," one of Naipaul's masterpieces.

The centerpiece of "A Perfect Pledge" is Narpat, a self-styled "futurist," a man who insists that independence, sacrifice, resiliency and inviolability are the path to success. Stay out of the rumshops, eat abstemiously, eschew fun and school bazaars, do not celebrate holidays — "What is all this airy-fairy nonsense I hearing about Christmas? ... People who expect these gifts without doing anything to deserve it is nothing more than gluttons" — that is Narpat's hard-core prescription for life as it should be.

His wife, Dulari, and his three daughters, Kala, Chandra and Sushilla, heartily disagree. When Narpat's son Jeevan, called Jeeves, arrives, his family conspires to subvert Narpat's joyless way of life, with little success.

Maharaj has a perfect ear for Trinidadian dialect and a perfect eye for life in the small village of Lengua in 1961, just before independence.

The story is by turns comic and tragic, as Narpat works the cane fields by day and strives to build a sugar-cane factory by night. He is indomitable in the face of weather, injury, the scorn of his fellows, the embarrassment of his wife and children and the futility of his efforts. He rails against the Brahmin across the street and his wife, Radhica, and is unaware of his children's nightly pilgrimage to their house to watch "I Love Lucy."

All of the minor characters are well-drawn real people, not convenient stereotypes. His true friend, Huzaifa, a bookstore proprietor, stands by him, as does Janak, the taxi driver, even though they can only shake their heads at his stubbornness. The Manager, a wily chiseler who has made a high art of corruption, and Doon, the local schoolteacher with literary ambitions, drift in and out of the story, the way neighbors often do.

Narpat lives to see the success of his children, in terms quite different from those he set down. When Jeeves asks him, "Why you spending so much time with this factory?" Narpat replies, "Because I can't give it up. Is a pledge. A perfect pledge ... Is when you willing to make any sacrifice to fulfill a promise you spent your whole life preparing for. Something that only you could do."

Jeeves learns this lesson well and puts it into practice at the end of Narpat's life. This eminently satisfying novel has the clarity of Naipaul and some of the bite, and a great deal that is Maharaj's own.