An Artful Installation

NOTHING ORDINARY about Breta Malcolm. She's wearing a long apron smeared with blues, whites, greens and oranges when she ratchets open the door to her weather-stained La Conner home. And there it is behind her — the extraordinary: a magnificent 9-foot-tall Guy Anderson painting of Icarus tumbling.

The piece fills the wall, looking like it was created just for that spot.

It very well may have been.

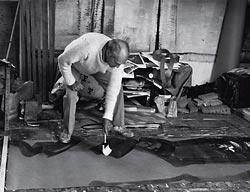

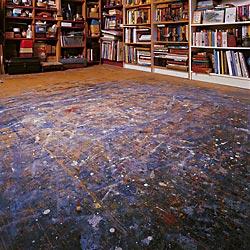

This tiny house with the big art originally belonged to the painter who has been called "the Picasso of the Northwest." He built the house and created in it. Malcolm bought it from his estate in 2000, and in 2004 added a master suite and garage. She calls it "that big piece of sculpture that I'm living in." His paint still pocks the studio floor upstairs. She felt destined to live here.

"The place just had a feeling about it, a magical, wonderful feeling, and I've felt like that ever since I've lived here," she says, sighing.

"Guy Anderson had been friends with (noted Seattle architect) Roland Terry for years, and he drew it up on a bar nap. The place just screams Roland Terry."

Anderson didn't need much, and he didn't have it in the tiny studio/home with only exterior stairs to the second floor. "I'm told he used a plunger and bucket to wash his three shirts," Malcolm says.

She lived near Volunteer Park in Seattle for 30 years, raising her two daughters. Now this house is for her. Malcolm previously worked for glass artist Dale Chihuly at his publishing company, Portland Press. In her new life, she sells real estate out of Anacortes and serves as a docent at the Pilchuck Glass School and the Museum of Northwest Art in La Conner.

She is a painter also, but finds "I'm much better off doing art as an avocation." When she moved to Anderson's place she thought she would paint more, but succumbed to the laissez fair La Conner life: "I spent all my time clipping back blackberries and fooling around."

A collector of art and whatever else strikes her fancy, Malcolm has made her surroundings a feast of form and fun from the floor up, like a rummage through the attic of an art museum. The original artist's quarters — 500 square feet on each of the two floors — are crammed with paintings, sculptures, shells from the beach, stones, stuffed animals, dried flowers and various other whatnots. Upside-down planters pose as table ends; suitcases are jam-packed with Chihuly glass.

Malcolm had her eye on the old Anderson place and bought it when it was "marked down, marked down, marked down. I got it for $160,000." The house was sinking and listing. Pilings pounded into rock set it right.

The addition gives her 540 square feet more living space. It also gives her a bright, airy master suite with birch ply walls, a deck and garage.

"Wherever there was a choice, Breta opted for the beautiful choice," Anacortes architect Brooks Middleton says. His biggest challenge was working around a commanding outcropping of bedrock. The thing just could not be ignored. So the upstairs deck wraps around the rock, and it serves as the imposing back wall of the garage.

Middleton makes it clear that this was no remodel. Anderson's place stands the way Malcolm found it. The addition is her legacy. In the end, Malcolm suffered from what she calls "architectural intimidation."

"I couldn't move anything in here because I thought, 'My stuff isn't good enough.' Then I thought, 'This is my stuff; get over it.'"

She did, and bought herself a serigraph to celebrate — Morris Graves' "Time of Change."

"I feel way lucky," she says, taking in the old and new, funky and functional. "I raised my daughters telling them, 'The only thing is, don't be ordinary. Ordinary is the worst thing.' "

Rebecca Teagarden is assistant editor of Pacific Northwest magazine. Benjamin Benschneider is a magazine staff photographer.

La Conner is a natural place for a museum devoted to Northwest artists. Four of the region's most influential artists, Guy Anderson, Kenneth Callahan, Morris Graves and Mark Tobey, lived in or spent time in the Skagit Valley.

On exhibit now through Jan. 8 is a retrospective of the work of abstract painter Frank Okada and glass-and-steel sculpture by Lisa Zerkowitz.

The museum, at 121 S. First St., La Conner, is open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday. Admission is $5, $4 for seniors, $2 for students and free for children under 12. The store features one-of-a-kind items from Northwest artists. Check it out at www.museumofnwart.org.