Success, In Stages

FAIRY TALES CAN come true in the big, bad world of Seattle real estate, but there can be a price: perseverance, help from family, a bit of luck, sacrifice and a whole lot of sweat equity.

That was the experience of Susanna Burney and Bliss Kolb, now in their mid- to late 40s. They were itching to get out of their small Capitol Hill apartment. Burney, an actress and director, was doing her yoga next to the stove in the kitchen; Kolb was suffering from the noise roaring out of a nearby nightclub. Plus he needed workspace for his design/fabrication business. The landlord had just shown up and said, despite the lease, "I'm gonna kick you out unless you pay more rent."

That was a few years ago. Then, as now, home prices seemed out of reach for people in the arts with freelance incomes. But they were determined. Bliss' father, Keith Kolb, a retired architect, reiterated his offer to design a house. He advised them to pursue the house they wanted, even if it had to be done in stages. The couple searched more than a year for affordable lots, or houses. Nothing. Nada. Misery.

Then one night, searching the online ads of The Seattle Times, Burney saw a lot for sale in West Seattle for less than $70,000. That next day she checked it out and knew at a glance it was the lot. They rushed, they found a Purchase and Sale Agreement, they signed.

To finance the lot purchase and house construction, Burney and Kolb turned to their parents. Each set vouchsafed about half the money, through home-equity loans; Burney and Kolb made the payments and contributed a small amount. Three years later, they refinanced via a conventional mortgage and repaid the parental largesse.

They spent a year and a half working with Kolb's father to design the space. Kolb acted as the general contractor, taking a three-year hiatus from his creative life to oversee the construction, and doing a good bit himself. Burney helped with the surface finishes.

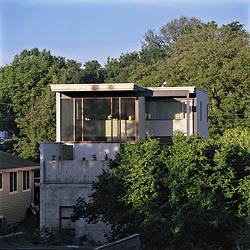

The result is a well-crafted, artfully conceived house as fitted to their needs as a tailor-made suit. The layout blends a warehouse live/work sensibility with a single-family home. Kolb has a cavernous workspace on the first floor. The living floors above include a great room with a wall of glass and a loft space dedicated to Burney's office and yoga. Smaller cubbyhole-ish spaces are gracefully blended with the more expansive house volumes, like eddies off the main current.

Somehow there's room for everything: That's the result of careful attention to the basic spatial logic of the house, the architect's bailiwick.

Total costs for construction were around $100 a square foot, plus a lot of anxiety and sheer tenacity. But for these two, the fairy tale of a home of your own, citadel of independence and privacy, has emerged.

David Berger is a Seattle freelance writer. He can be reached at dab20@aol.com. Benjamin Benschneider is a Pacific Northwest magazine staff photographer.

Design is key to a satisfying but affordable house. Here are some of the strategies employed by Bliss Kolb and Susanna Burney, and the architect, Keith Kolb:

Small Footprint. The total living area is about 1,500 square feet, which reduced costs yet allowed each space to be highly considered, with nooks and crannies that make for functionality and pleasure. Plus, there was something left for extras, like three skylights that bathe the interior in natural light.

Pocket Doors. Pocket doors make the most of the available square footage, and room dividers enable small spaces to do double duty.

Cheap Materials. For the floor, the couple used oriented strand board, the most utilitarian wood product out there. But cutting it up into square tiles, then staining and sanding, resulted in a subtle, satisfying, multihued surface. The finish trim is mixed-grain fir, less costly than the few sticks of vertical grain also used, but with the same rich color. The outside sheathing is corrugated metal. In the bathroom, they used recycled tub, sink and toilet fixtures, salvaged marble and tile from Home Depot.

Staged Construction. Susanna and Bliss moved in before the kitchen was installed and worked on the house while living in it. Many details remain for when time and money allow.

"Some people buy an old house and fix it up," says Susanna. "We built a new house, and we're fixing it up."