A Meeting Of Minds

DURING THE BLESSING, Maya Lin sat on a plastic folding chair on a small island in the Snake River, basalt bluffs on either side, migratory flyway above, tribal history behind. Ahead lay the creation of seven major public artworks along the route traveled by Lewis and Clark.

The series, called the Confluence Project, will stretch from Washington state's foggy forested coast to inland arid plateau; reach backward and forward in time; cross cultures. Two hundred years ago, people and cultures gathered where rivers met. At key confluences along the Columbia River Basin, Lin's artwork will look at the landscape from the perspective of the tribes as well as the explorers.

It is the largest and longest project the renowned artist and architect has undertaken since launching her career at age 21 with the design of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. Here, in Washington state, she plans to break ground at Cape Disappointment in the fall and work east, finishing with an island amphitheater, a natural "skybowl" at Chief Timothy Park outside Clarkston in 2007.

At the moment, here in the skybowl, there is sun and ceremony. Rain had been forecast, but "Uncle" Horace Axtell, the 80-year-old spiritual leader of the Niimiipuu, the Nez Perce tribe, delivered on his promise to "take care of it." Actually, Uncle hadn't planned to get involved with the Lewis and Clark bicentennial at all: "You put the whole history together and there's a lot of bad things happened since those two guys came over here."

But he wanted to do this for Maya. She'd listened to his stories — the land lost, treaties broken, ancestors killed. She'd listened to the river. She understood. It's hard to heal somebody's loss. Yet she'd honored those warriors on the Wall. That war was hard to explain. Every war is hard. Uncle served seven months in Nagasaki and Hiroshima after the atomic bomb. So many poor little kids, such stench, he couldn't eat. It didn't seem right to kill so many people in their own homes. Wasn't right then, wasn't right back in 1877 when soldiers captured the Nez Perce Red Heart band and locked them in stockades at Ft. Vancouver. Women, elders, children. Nobody has forgotten the Nez Perce baby boy who died there.

"Anyway," Uncle says, "some day people will talk about peace. That's a big word. The only time you really have peace is when you sleep. My ancestors tell me that when you take it back to the time of the first people, the Creator gave us language and land. For a long time the people lived at peace on this land. Every morning, as soon as they woke up, they thanked the Creator. Qe'ciyew'yew'. Thank you."

Uncle rang a bell in the clear morning air. Qe'ciyew'yew'. On rows of folding chairs, tribal members sat next to state officials, teachers, a mayor, a millionaire donor, a sneezy dog, the former commander of Ft. Vancouver. Qe'ciyew'yew'. Uncle sang, prayed, beat an animal-hide drum. Qe'ciyew'yew'. Lin was moved to tears.

"Would I have even dreamed five years ago I would be part of a Nez Perce blessing ceremony?" she asked, walking through dry fescue and yellow-petaled balsam root after the blessing. "What we just witnessed today, I feel an incredible responsibility. Not just sympathy. You feel like working really hard not to disappoint, and that has nothing to do with tourism. It's on a human level, intimate, about the larger landscape. This place has a power. For me, it's about the land. For them, it's the Creator. For everyone, it's something.

"I get so many proposals I have to turn down. I had retired from the monument business. But they were like: We don't have that much to celebrate in these last 200 years. Can you give us a reason to celebrate? They asked me because I'm a committed environmentalist. Once I realized it wasn't about anger, it was more like: What is this about? . . . Can we rethink things we think we already know? "

EVERYBODY AGREED Maya Lin was the perfect choice, but few believed she'd sign on.

In the beginning, there was no money, no connections, no place, no permits, no support. Just a grand idea that, coincidentally, came at almost exactly the same moment to an assortment of characters living up and down the Columbia River Basin.

In May 1999, on a Wednesday evening in the Blue Mountain foothills of the Umatilla Reservation, Antone Minthorn plopped down on his living-room couch and popped a documentary about Maya Lin into his VCR. The chairman of the Umatilla Confederated Tribes had watched it before, but this time it crystallized as a solution.

What to do about the upcoming bicentennial? Not a celebration. Not another statue of two guys pointing West. That expedition, in Minthorn's eyes, was a collision between Manifest Destiny — conquer the West — and native beliefs about respecting the earth. "Manifest Destiny is very exploitive," Minthorn says, "very aggressive, relying on a lot of technology, a lot of greed factors. Wealth is created for those who claim it first, but a lot of damage is done."

The tribes believed no one owns the land though they could share in its spirit, food, medicine. Take only what you need, Minthorn explains, make sure there are resources for children seven generations ahead. In the video, Maya was clearly passionate about the environment, and brilliant, Minthorn could tell, from her work on the Wall, the Civil Rights Memorial, the Women's Table. Even more, the tribal leader admired her persistence. "The great things," he said, "you have to fight for them."

The next day, Minthorn called David Nicandri, Washington State Historical Society director coordinating bicentennial events. A minute later, Nicandri's phone rang again. Jane Jacobsen from the Vancouver National Historic Reserve Trust: Instead of every city squabbling for funds to make a bunch of scattered statues that wouldn't add up to much, she said, how about a series of artworks along the river — designed by Maya Lin?

Nicandri laughed. "Did Antone tell you to call?" he asked. No, she said, haven't seen Antone in a month. She and David DiCesare, who managed the Vancouver Historic Reserve, had been thinking about the circle of history and realized, "Wait a minute. Lewis and Clark didn't discover the West. They didn't even open it up. They just happened to come through here with the help of the tribes. So what was the land like then? The cultures?"

Well, if you're serious about this, Nicandri told them, call the coast, Pacific County. They're doing something big because that's where Lewis and Clark first saw the ocean.

"Nabiel," Jane rang the Long Beach city manager. "What are you all thinking about for public art?"

Nabiel Shawa launched into a rhapsodic riff about how Pacific County had the richest Lewis-and-Clark history in the state, how this was where the explorers completed their mission, first walked the rugged shore, saw condors and sturgeon and carved their names on the trees. Deep breath. "And I know we're the poorest county in the state, and I know you're going to laugh," he paused. "For our first choice we're thinking of Maya Lin."

BUT MAYA LIN was not thinking of them. She'd just finished "Boundaries," a visual and verbal sketchbook about her work and philosophy, and was itching to launch her pet project, "Extinctions," to monitor biodiversity and man's relationship to the environment around the planet. Plus, she had art and architecture projects and two small children.

Back in the Pacific Northwest, Jacobsen met with Minthorn and a few others who would eventually form the core Confluence team. They sent a proposal to Lin. "We didn't even talk about money," Jacobsen says. "Why talk about money when you can talk about fun stuff? It was just a great idea. And you can't just let a great idea hang out there." (The project budget is $22 million. The nonprofit has raised $13.5 million so far from government sources, foundations and private donors. Of that, Lin's fee will not exceed $1.2 million.)

As Jacobsen tells it, they didn't hear back from Lin for several months, and took that as a good sign.

"I DID respond," Lin said during breakfast in Clarkston before the blessing ceremony. "I said, NO! Many times! I get calls about commemorating historic events all the time. It's not what I'm interested in. I don't want to be typecast, stuck in the commemorative Monuments-by-Maya."

So what turned the tide?

After FedExing the proposal, the Confluence team returned to their lives: attending meetings, filing taxes, fishing. Months later, on a rainy Thursday at midnight, Jacobsen flashed on DiCesare's family trip to his niece's wedding in New York. Manhattan . . . Maya! DiCesare had flown to the East Coast that morning, but no matter, Jacobsen left a late-night message at the hotel: You're in New York and we haven't heard back from Maya. Why don't you get in touch with her and see if she's interested?

Next morning, DiCesare and his wife, Lynn, set off from their midtown hotel with Lin's address on a scrap of paper. "Let's just walk down there and see what comes of it," he said. They found the street, an old industrial door, nameplate "LIN" by the buzzer, and told the receptionist they were from Vancouver, here to talk with Maya about a project. She's not here and not expected. They were just about to leave when Lin's assistant walked up, coffee in hand. All the way from Washington state? Well, c'mon up. They were in the second-floor loft explaining the project when Lin arrived and listened in. Oh, that's interesting, she said, tell me more.

She made a pot of green tea and pored over an atlas as they talked about the Columbia River Basin, the incredible changes, the dams, population growth, the rapid urbanization of the Vancouver-Portland area. Lin was fascinated by the diversity of landscape from east to west, by the role of salmon as a unique species, by the tribes.

"We just met one of the great artists of our time," DiCesare told his wife. "The thing that really struck me was how focused she was on learning and understanding the project. She asks lots of questions. She has an extremely inquisitive mind."

Months passed. Still no word.

Enter Gov. Gary Locke. Like Lin, he is an alumnus of Yale University, and though their time there didn't overlap, their paths have since crossed as two of the country's most prominent Chinese Americans.

One night, Jacobsen attended a fundraising dinner in Vancouver. Locke visited each table, and when he got to hers, she told him they'd invited Maya Lin to create artworks along the Columbia River. "He jumped up and said: 'This is a great idea! Very exciting! I know Maya. We both went to Yale! What can I do to help?' "

Locke wrote a letter, got no response, followed up by phone. "I think she'd just come back from maternity leave and was swamped with stuff, with requests, so I called her. We chatted about how we both have young kids, and I told her the Confluence organization was a credible group and how much everybody loves her work and we'd be so honored to have her work in the state of Washington."

Lin requested more information. The Confluence team sent books, maps. Struck by inspiration, Jacobsen asked everyone to collect something from their site: a stone, sand, feather, shell, stick, handful of earth. If Lin had such strong physical attachment to the land, why not wrap it up and send it to her?

Shawa thought mailing a box of rocks was odd, but went along. "I didn't know how it would contribute to the creative spirit or have anything to do with Lewis and Clark or the indigenous spirit, but who knows how art works? Maybe the rock is a muse! I'm a bureaucrat. There was no 5-inch report!"

They waited.

In 2000, the day before Thanksgiving, Lin left a message on Jacobsen's voice mail: Y'know what? I'm going to do this for you guys.

THE FOLKS WHO dared send rocks to New York City traveled to Lin's Soho studio themselves in May 2001, a trip funded by an anonymous donor.

It was a warm day, windows open, horns honking, sidewalk conversations floating into the cavernous studio with models of projects on tables and a whole wall of bookcases. They sat and told their stories, the coast first, then heading east. Lin listened.

Cliff Snider, an avid fisherman and 78-year-old honorary chief of the Chinook, told Lin about salmon. "The Chinooks were a rich tribe because the grocery store was their environment, beaches for clams and the river for salmon." Once the river was so thick with fish, he said, you could walk across their backs. He told about dams disrupting the salmon's natural life cycle. About his tribe's upstream fight for official recognition. About how much had changed in only 200 years. "Just imagine coming down the Columbia Gorge at night. All along the river, every village has 40 or 50 bonfires going. Wouldn't that be a sight to behold?"

Minthorn told Lin of the Umatilla Confederated Tribes' success in restoring water and salmon to the Umatilla River. How that was a treaty right. How they believed in sustainability. "We want the mountains to be mountains. We want these watersheds so we can have clean water for our children and their children."

Jennifer Oatman, a Nez Perce mom, said hearing about past mistreatment of tribes always made her sad. She told of ignorance and prejudice she'd faced growing up in Idaho. She talked about the next generation, and how she hoped children would never ever hear the verbal insults she's endured. She got teary: I want people to know we've been here, we're still here and we'll always be here.

THIS SPRING, near Cape Disappointment, Maya Lin searched for "personalities" among the enormous driftwood cedar logs on Benson Beach. These will become totems hovering near a crushed oyster-shell circle. "The problem with cedar," she confides, "is it grows straight, and if you're not careful, you're going to have telephone poles."

Then she headed for a basalt quarry outside Spokane, where, she says, "As an artist, I was in heaven." She chose a six-sided chunk with rusty patina and dark core that will be perfect as a fish-cleaning station at Cape Disappointment. She'll polish the top and inscribe it with a Chinook creation story, how a drop of blood from a salmon became the egg that became the tribe's first person.

"Isn't it cool? A symbolic fish altar," Shawa says. "At the same time, you're going to be able to clean and gut your salmon on this sculpture created by an international artist."

At each site, Lin will quote the Lewis and Clark journals. She loves the idea of stretching a book through physical space and real time.

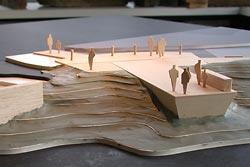

At Sacajawea State Park, she'll inscribe a day's entry on dock planks. Nearby, she plans a compass pointing to tribal homelands, showing size and how many days away by foot, then and now. At Sandy River Delta, one of two Oregon sites, she plans a gently spiraling ramp, bird blind at the top, fence planks inscribed chronologically with all the birds and mammals Lewis and Clark classified, and each animal's current status, endangered or extinct. In Vancouver, a 40-foot-wide earth-covered landbridge will float above traffic, linking waterfront with the National Historic Reserve.

At the "skybowl" outside Clarkston, Lin will allude to the history of the Nez Perce tribe. One oft-told story is how Nez Perce boys digging camas roots spotted members of the Corps of Discovery, hungry, lost, bedraggled. Because of the men's light eyes, body hair and disheveled appearance, the boys weren't sure whether the explorers were human, fish or animals, says Wilfred Scott, a Nez Perce elder. Tribal warriors wanted to kill the strangers, but an old bedridden woman counseled, "Do them no harm." So instead, the tribe helped and traded with the Lewis and Clark party. "If not for her," Scott says, "it's possible the Corps of Discovery would not have passed through."

Time, place, people 200 years ago. Lin will relandscape, remove riprap, use indigenous plants common in centuries past. These days, many of the river confluences are surrounded by brutally ugly modernization — tank farm, junk yard, paper mill — but Lin has found nearby quiet spots she hopes will have environmental meaning.

"This is not about the pristine idea of Native Americans and returning to the land. Fundamentally, it's about how we treat the land, how we see the land, how we want to own the land . . . . I'm reticent to make an artistic statement calling attention to itself. I want to connect you back to the landscape, make you pay a little closer attention to where you are, maybe who you are.

"Two hundred years from now, we might be living in a better place," Lin says. "Right now, we're at a huge crossroad."

Paula Bock is a Pacific Northwest magazine staff writer. She can be reached at pbock@seattletimes.com. Alan Berner is a Seattle Times staff photographer.

Crossing cultures and time through art

Confluence Project planners envision seven public artworks commemorating the landscapes and peoples encountered by Lewis and Clark 200 years ago. Some of the ideas for the sites are in the early stages of development, and financing for all projects is not yet complete.