Monorail may sink dream for Pioneer Square's Sinking Ship

Six decades later, his family could be forced to sell the property to make way for the monorail.

The Seattle Monorail Project (SMP) says it needs the land for a station at Second Avenue and Yesler Way. It would be a hub just 90 paces from the regional bus and light-rail tunnel, serving Smith Tower and government office buildings.

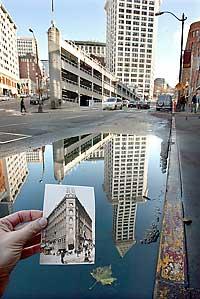

The property is now occupied by a quirky angular parking garage nicknamed the Sinking Ship, which would be demolished to make room for the station. The Kubota family doesn't oppose a monorail, and they too would like to raze the old garage, which the neighborhood seems to agree is an eyesore.

But they are fighting SMP over who will control the land's future.

The station can fit on less than half the triangle. Monorail officials are trying to condemn the whole site and use the leftover land as a storage yard for construction materials, then resell it after the line opens five years from now.

Kubota's son-in-law, John Fujii, has taken the dispute to a state appeals court, after a King County judge ruled in SMP's favor. Fujii wants to build housing there, with retail on the ground floor.

"We have held on to this property 64 years," he said. "We would not have held it this long unless we planned to do something important at the site."

The three-level garage, which appears to list in a concrete sea, last made news in 2001 as the perch where police commanders and news cameras witnessed a fatal Mardi Gras riot in Pioneer Square. Frommer's Guide calls the garage "the monstrosity that prompted the movement to preserve the rest of this neighborhood."

"It's one of the ugliest things in Seattle," acknowledges Kubota's daughter, Doris. She and Fujii own the land beneath, while a tenant runs the garage under a long-term lease.

Earlier, it was the site of the Seattle Hotel, a favored stop for Alaska gold prospectors that was built after the great 1889 fire.

Kubota, an immigrant railroad laborer and hotel manager, bought the hotel in February 1941. Soon after, Japan's air attack on Pearl Harbor drew the United States into war, and Japanese-Americans were sent to internment camps.

Kubota was shipped inland to Camp Minidoka in Idaho under Executive Order 9066, which displaced 110,000 people. While other Japanese-Americans lost their land and businesses, Kubota was helped by a prominent Seattle landowner, Charles Clise, who agreed to manage the hotel. Clise described Kubota as a man of "ability and competency of an outstanding quality" in a letter that helped the family win release from the camp to go pick sugar beets in Colorado.

In January 1945, Kubota and another internees returned home to a cordial welcome. The hotel had to be repaired after an earthquake four years later, and it was demolished in 1961. A developer announced plans to build a six- to eight-story office for Standard Oil atop a parking garage. To Kubota's dismay, only the garage and a gas station were finished.

Nonetheless, the family stuck to a long-term lease with garage operators, awaiting its chance to someday erect the high-rise Kubota wanted.

Condemnation

Conceivably, the monorail project might help the Kubotas realize their dreams. Without any monorail condemnation, the garage operators would continue their lease possibly until 2020, Fujii says.

With a condemnation, Fujii hoped to cooperate with SMP, forging a deal where he could develop the leftover land years sooner. And a station would likely make residential or commercial development on the site more attractive to developers.

Fujii hired an architect to make a conceptual drawing of a 10-story housing tower, in the belief he could co-develop with SMP, as the agency is doing near the Pike Place Market with the Samis Land.

He offered to sell the agency enough land for a station, then rent out the remainder until construction is completed. But the monorail's right-of-way manager, Joe McWilliams said paying years of rent would be too expensive.

Fujii believes the agency's real aim is to cash in on the Kubota land, to help make up for a shortage in the monorail's car-tab tax.

Last year, SMP published a report predicting the stations would boost land values as happened near commuter stations in Portland, San Francisco and Vancouver, B.C. Monorail officials point out that their current budget projections do not depend on money from land deals. However, the agency has paid for feasibility studies of development around stations. SMP will not release its study for the Sinking Ship site.

"We, as a public agency, are required to look at all of our assets and get the best return we can, for the taxpayers," McWilliams said.

The assessed value is $4.5 million. The SMP has offered Fujii $6 million. He says money isn't the issue.

"It has a lot of symbolic value to us," he said. "Instead of losing it in the internment, isn't it ironic that 64 years later it's going to be taken from us? The voters of Seattle need to know what kind of a project they have."

Monorail spokeswoman Natasha Jones said the dispute is part of doing business in a setting as rich in history as Seattle. Staffers are trying to think of a way to honor Kubota, perhaps using the agency's public-art program.

In another appeal involving surplus land, Korean immigrants Young and Taiki Lee, who own Cafe Appassionato near the Space Needle, refuse to leave their tiny triangle off Broad Street. They argue the monorail doesn't need the piece — and therefore does not deserve to condemn it. The spot appears as a landscaped zone, in a SMP architectural concept.

Eyesore

The notoriety of the Sinking Ship garage has attracted proposals and political pressures that sometimes overshadow the Kubota family's role.

The SMP has made the public-relations point that the project could improve the neighborhood — publishing an image of a fountain, new street trees and fuschia-toned banners around the proposed Yesler station.

William Justen of Samis, which owns Smith Tower next door, has suggested a pedestrian promenade, a low-rise building with retail space and underground parking. A park also has been suggested, but that drew opposition because Pioneer Square open spaces already are afflicted by drug dealing and loitering.

The Pioneer Square Community Association, which has held dozens of public meetings about the property, would like to partner with Fujii to build an affordable housing complex for people earning $30,000 to $42,000 a year, executive director Craig Montgomery said.

"To me, it's a very compelling story as to why the family should continue to have an ownership interest in that space," he said.

Mike Lindblom: 206-515-5631 or mlindblom@seattletimes.com

|