On a collision course with the NFL, Dave Pear is playing to win

Desperate to rally his team from behind in Super Bowl XV, Philadelphia Eagles quarterback Ron Jaworski drops back to pass. Oakland Raiders nose guard Dave Pear breaks through the blocks and lunges for the quarterback, grabbing him by the thigh before burying his helmet into his gut. The split-second before Pear levels him, Jaworski tosses a wounded duck that hits a Raiders defender square in the chest for an easy interception, but he drops the ball.

"Tribute that bad pass to the pressure of Dave Pear," bellows Merlin Olsen, a former NFL defensive lineman providing color commentary on TV.

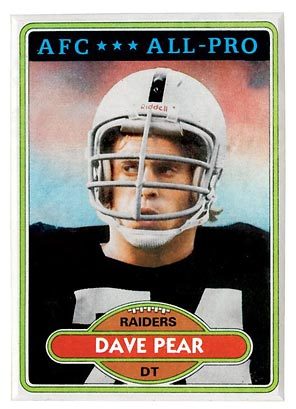

A big play in the biggest of all games, the moment is captured in a black-and-white souvenir photograph that Pear displays in the living room of his house overlooking Lake Sammamish. On the same shelf is a framed 1980 football card declaring Pear an "All-Pro," along with a football signed by his Raiders teammates, who ended up winning the Super Bowl, 27-10.

Pear sits on his sofa, watching a recording of the January 1981 game. He is wearing his University of Washington letterman jacket, which still fits, and his Super Bowl ring, gleaming with 35 diamonds.

"When you see my Super Bowl ring, you think these must have been good days, but this was a most unpleasant time in my life," Pear says. "These were the days they were giving me pills and shots and pushing me out on the field."

Like other players from his era, Pear pursued a career in professional football believing that if he made himself strong, worked hard and put team above self, he would be rewarded. The game, much simpler then, would take care of him.

But it hasn't.

"Football is not a contact sport, it's a collision sport, and when collisions occur, there are going to be life-changing, life-altering injuries," Pear says.

His occurred Sept. 16, 1979, in the Kingdome against the Seattle Seahawks. While tackling running back Sherman Smith, a disk in Pear's neck popped out of place.

"It felt like lightning shooting down my spine," he recalls. "I made the tackle, but I was the big loser because the injury changed my life."

Playing wounded for most of two seasons, his last pro football game was Super Bowl XV. His NFL career was over at 27, having lasted six years — about twice as long as average for a pro football player.

As Pear lived out the boyhood dream, he never fathomed life as a 54-year-old husband and father too crippled to work, dependent on a cane to relieve the pressure and pain on his lower back. Once considered among the NFL's 10 strongest men, Pear has had seven spinal surgeries since 1981. In the next three years, he plans to have both hips replaced and have doctors remove four bolts inserted in his lower back last April. Pear believes the screws cause the numbness that shoots down his legs and into his toes.

Pear also shows signs of early-onset dementia, a condition that has plagued other players of his era and one doctors tend to attribute to repetitive brain injuries suffered on the gridiron. He sometimes forgets why he started a sentence and has trouble staying awake, making it tough to hold a job. He downs 15 to 25 prescription pills daily to dull the pain and keep from falling asleep.

He figures he has spent about half a million dollars in out-of-pocket medical expenses since leaving the game — more than he ever earned during his NFL career.

Pear also suffers the strain of feeling like the game he helped build has turned on him. He is determined to expose what he views as a morally bankrupt NFL retirement system that has denied disability benefits to his family. Considering what could be, Pear is fortunate. Some of his peers are penniless, alone or dead. He, on the other hand, is able to keep his problems in perspective with a comfortable home, a loving wife, two bright children, nice friends and profound faith as one of Jehovah's Witnesses.

In his playing days, Pear was a pain for opposing quarterbacks despite being undersized for a defensive lineman. These days, he is taking his best shots at the NFL and the NFL Players Association, the union representing current players. He is an outspoken leader on a team of former NFL players, including household names like Mike Ditka and Eugene "Mercury" Morris, who are taking their case to Congress and the media.

Players association executive director Gene Upshaw, Pear's teammate in Super Bowl XV, uses a single word to describe Pear as both former player and current antagonist: "Relentless."

Pear is convinced that when politicians and the public learn how dismissively the NFL and union have treated the game's former greats, it will make jailed Atlanta Falcons quarterback Michael Vick's treatment of dogs seem tame by comparison.

IN HIGH SCHOOL in Portland, Pear's football coach gave him a 34-pound dumbbell to help bulk up. He curled it 5,000 times, without stopping, four or five times a week. His mother saw football as a way for her son to get a scholarship to college, and he received offers from several Pacific Northwest universities before choosing Washington.

"He clearly was a notch above most of the rest of the guys on our team in terms of ability and work ethic," says Ray Pinney, who played center for the Pittsburgh Steelers and was one year behind Pear at Washington. "He was always in the weight room."

Washington's athletic department promoted Pear as an All-American before his senior year, publishing a poster of him stopping a moving train.

"I thought he was invincible," says his wife, Heidi Pear, who met him at the UW. "He would bounce right up after a play and do it all over again. It didn't seem like it was a big deal."

Selected in the 1975 NFL draft by the Baltimore Colts, he played a year there as a reserve. The Tampa Bay Buccaneers, a new franchise in 1976, selected Pear in the expansion draft, and his career took off even though the team did not. Losers of their first 26 games, the Bucs were the NFL's laughing stock, all the way down to their hideous bright orange uniforms.

Searching for someone to love, Bucs fans gravitated to Pear. In the stands, they imitated his on-field celebrations.

"After he made a sack or a big tackle, he'd come up from the pile with both fists raised," recalls Floyd DeForest, a commercial fisherman and former beer-truck driver who was president of Pear's fan club. "He played every play like it was his last."

After the 1978 season, Pear earned a spot in the Pro Bowl, the NFL's all-star game, the first Buccaneer so honored. Also after the season, he demanded more money from the thrifty Bucs, who were paying a higher salary to Pear's backup. The team responded by trading him to the Oakland Raiders.

Pear has kept a couple "Dave 'The Bear' Pear" fan-club T-shirts from his Tampa Bay days as mementos. They hang in his bedroom closet with several jerseys, including the one he wore in the Super Bowl. In the same closet is a plastic tub full of other vestiges from his playing days: a 1973 Huskies Player of the Year trophy, a game ball presented to him that same year, a 1977 picture of the Tampa Bay bench after the team lost its 26th straight game, two unused tickets from Super Bowl XV, and a folder of medical reports and X-rays.

BY THE TIME Super Bowl XV rolled around, Pear's left arm and the left side of his chest had atrophied to the point he was shy about removing his shirt.

"The whole mentality was if you could walk, then you could play," Pear says. "You always thought when you got hurt, the team would stand behind you and take care of you medically. That's what employers do when you get hurt on the job."

Pear says Raiders doctors never acknowledged the severity of the injury, advising him to rest while plying him with Percodan and needles to deaden pain and reduce swelling. The Raiders cut Pear during training camp the summer after the Super Bowl, saying he seemed to have lost his desire for the game. At his own expense, an out-of-work Pear underwent an operation at Stanford Medical Center that December. Doctors diagnosed his injury as a cervical herniated disk. Surgeons used a special drill to bore through the calcified bone.

Pear first applied for NFL disability benefits in 1983. A six-member retirement board split on the case — union trustees voting in favor of granting the benefit, management voting against. An arbitrator cast the deciding denial. Pear says the final decision should have been made by a physician not an arbitrator, and after repeated attempts, he finally got NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell on the phone to make him listen to his grievance.

In 1995, Pear applied for disability again, this time under a different standard that grants benefits if a player can show his football-related injury is permanently debilitating. The retirement board ruled Pear was healthy enough to perform sedentary work and denied the claim. Believing he never would receive disability benefits from the league, he applied for the NFL's early-retirement benefit at age 45, for which he now receives a monthly check of around $600. Had Pear waited to take his pension until this year, when he turns 55, the check would be much fatter.

But Pear is not in financial crisis. His wife works, their children chip in, and Pear has begun receiving a Social Security disability benefit of about $2,000 a month.

Pear says this fight is not about him. What it is about, he and other retired players say, is that the NFL and union's standard for awarding disability benefits is ridiculously high, and that benefits too often get denied on technicalities. They argue the union cares only about padding a billion-dollar pension and disability fund that exclusively benefits current NFL players — players who earn an average salary of $1.4 million a year. Making that kind of money, the old guard argues, current players can afford to care less about how they'll manage when their playing days are done.

A PRO FOOTBALL PLAYER rarely retires on his own terms. He is either forced out by injury or told he no longer is of value to the team. That psychological toll plays into the fury that some NFL retirees feel today, says Upshaw, the union boss who himself retired in 1981.

"The cheering stops," he says. "When a player leaves, the team puts that jersey on someone else and keeps playing. The player keeps thinking, 'Hey, I used to wear that jersey. And now no one cares about me.' "

Upshaw says rulings on disability benefits to ex-players follow federal law, from which the union cannot deviate. But Upshaw also knows no explanation he gives will ever be good enough for retirees like Pear, who peppers NFL and union in-boxes with salty e-mails, sometimes three a day, demanding documents, answers, attention.

"We all knew what we were getting into when we got into this," Upshaw counters. "We all got paid whatever we got paid, and we all understood the risks we were taking."

Upshaw and Pear played in an era when pro football posed greater dangers and offered fewer rewards. Many fields were AstroTurf, a synthetic that's about as forgiving as concrete. Opposing players dished out head slaps, leg whips and chop blocks — dirty tactics that all are outlawed today.

Older retirees would deny it, but the amount of money players make today has got to grate on them. Before ever taking a snap as a pro, JaMarcus Russell, the No. 1 pick in the 2007 NFL draft, signed a contract with the Raiders that guarantees him $32 million. In Pear's day, some players took jobs in the off-season to pay their bills. Pear's first contract was for $30,000 plus a $30,000 signing bonus in 1975, $40,000 the second year and $50,000 the third.

"That was considered a good contract back then," Pear says. "Back then, players were paid on performance. Now they are paid on potential. Don't get me wrong. Current players are not overpaid. They deserve every penny they get. But they forget that the reason they are getting these huge contracts is because of the players before them who broke their backs and necks for the game — and now are being pushed aside by the NFL and NFLPA and being told to deal with their lawyers."

Upshaw says vitriol toward the union is misplaced. Union bargaining, after all, is responsible for today's big-buck pay scale. And he says the union has done a lot to help older retirees, such as forming a trust that has paid out more than $1.5 million over the past 18 months to former players in dire straits. Last year, the union and NFL announced the creation of a $17 million fund for players undergoing joint-replacement surgeries and other medical procedures. Pear, whose hip replacements could be covered by the fund, says "the NFL has so many hoops to jump through, I wonder how many players actually will qualify for this benefit."

Since Upshaw took over the union in 1983, the share of NFL revenue going to players has increased from 30 percent to 60 percent during a time of skyrocketing revenues. Forbes magazine reports the average value of an NFL team is $950 million.

Mercury Morris, a former running back who helped the Miami Dolphins win consecutive Super Bowls in the early 1970s, says the NFL and the union are no longer adversaries but instead complicit.

"When owners gave the players the power over the money, that took the responsibility away from the owners and put it on the players," Morris says. "So the first thing a player does is act like an owner. Putting the NFL and particularly the NFLPA and its trustees in charge of the welfare and benefits of the retired players is like putting the Klan in charge of civil rights. It fundamentally cannot work."

IT'S A SUNDAY afternoon in November and the Seahawks are poised to explode for a comeback victory against the St. Louis Rams. Pear doesn't bother switching off the TV as he leaves his house to go where he spends every Sunday afternoon these days, the Jehovah's Witness Kingdom Hall in Issaquah. A Bible passage is stenciled on the mocha-colored wall behind the pulpit: "The great day of Jehovah is near." A glorious future promised by Jehovah gives Pear comfort today, as does an extended family of other Jehovah's Witnesses who greet him with firm handshakes and genuine concern about his health.

Pear, a former Catholic, shares a pew with his wife and two children.

Heidi Pear sometimes has had to work two jobs so the family could pay its bills. The couple's children, both in their early 20s, still live at home to help care for their father financially, emotionally and spiritually. The son, a good athlete, took his parents' hint and chose not to play football.

Neither of the Pear children wants publicity, and Heidi Pear says the last thing her family seeks is pity. They live a good life, she says, although she and the children have sacrificed plenty. Pear missed much of his kids' growing up, spending a lot of time away from home after he left the game, working various outside sales jobs that his back couldn't hack. Many family decisions, financial and otherwise, have been based on whether Dave Pear ever can work again, and how Heidi and the children will manage to take care of him when he no longer can take care of himself.

Pear says families of NFL players suffer the greatest hardships. "My wife, my daughter, my son — they didn't make the decision to play professional football. I did. And yet they pay the price for my decision every day."

In some cases, families are the only ones left to speak for their loved ones. One of Pear's teammates in this cause is 23-year-old Garrett Webster, the son of Hall-of-Famer Mike Webster, a former Pittsburgh Steelers and Kansas City Chiefs center who played from 1974 to 1990. As a teenager, Garrett Webster stood close as his father was reduced from a Super Bowl hero to a beggar living out of his truck. His body hurt, his brain battered, his behavior had grown bizarre. Mike Webster died in 2002. His family sued the NFL over Webster's retroactive disability benefits, winning a $1.5 million judgment.

"Just think about the shame my father felt," his son says. "Here was this hulking man who bench-pressed 500 pounds and then couldn't make it down the stairs without crying in pain. That's one hell of a fall, you know?"

Stuart Eskenazi is a Seattle Times staff writer. Harley Soltes is a Seattle-area freelance photographer.

To learn more

For further information on the retired players, their fight for benefits and the union's viewpoint, see: