South Lake Union streetcar on the past track

On the brink of an economic boom, Seattle businessmen promoted a streetcar line along Westlake Avenue, where they dreamed the tracks would spark more business and home construction.

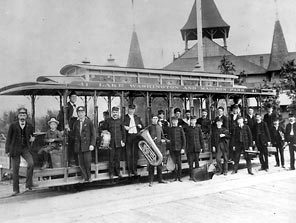

The year was 1890.

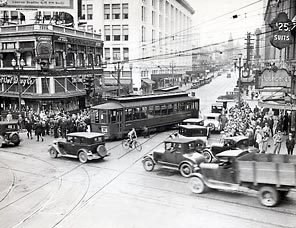

Built in just five days, the Lake Union line became part of a 70-mile collection of electric and cable-car lines that put Seattle on the cutting edge of transit innovation when the 20th century arrived. The streetcar age ended in 1941, when the system succumbed to money shortages, new highways and buses.

More than half a century after, another streetcar is coming to South Lake Union. The line, which opens Wednesday, is the first link in what boosters hope will become a new streetcar network.

"Within 20 years, we could build out a system of five, perhaps six lines," said Mayor Greg Nickels.

Even as the region waffles on a replacement for the Alaskan Way Viaduct, a new floating bridge for Highway 520, and suburban extensions of light rail, the city has completed work on a 1.3-mile streetcar route — the path of least resistance.

This time, the line took three years to plan and 1 ½ years to build. Not five days, but quick by modern Seattle standards.

For $52 million, half from a tax on nearby properties, the city gets rail service at 11 stops, from the Westin Hotel to the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. The line is part of the city's goal of bringing 16,000 jobs and 8,000 housing units to South Lake Union by 2020. More than 6,500 jobs have arrived since 2000.

The streetcar is meant to attract tourists, serve the cancer center, and help a new wave of office workers run errands downtown. For some, it will be a connection to express commuter buses or future regional light rail, at Westlake Center. Tracks run along the edge of Lake Union Park, which is being expanded and rebuilt with the idea that it will become a popular destination.

Where we've been

Phyllis Lamphere, 85, rode the original, gold-colored Lake Union streetcars in the 1930s, from working-class Wallingford to her Sunday school and ballet lessons downtown.

"They're rattling, they're noisy, they're anything but plush," she remembers fondly. It was a two-foot climb to enter the cars, where she grasped a brass handle on the back of the wicker seat. "They sort of smelled like straw."

The cars ambled across the Fremont Bridge and past the west shore. She could see the last houses atop Denny Hill, which was razed over three decades.

Lamphere, who went on to serve on the City Council, compares the old trains' bumpy ride to the George Benson Waterfront Streetcar, a tourist line using vintage Australian cars when it ran from 1982 to 2005.

Where we are

The three new South Lake Union streetcars, imported from the Czech Republic, accelerate to their 20 mph cruising speed on the straightaways so smoothly it's like riding on air.

Drivers, supplied by King County Metro Transit, are being taught to avoid what Carl Jackson, an operations supervisor, calls the "nod factor," where a quick stop yanks the passengers' heads forward. Nods are common on a bus, but Jackson insists that the trains stop gradually.

Tickets are purchased from a machine in the center of the train, on the honor system; Metro supervisors will sometimes roam the trains and ask to see a ticket or pass. Readerboards at each station will show when the next train is due.

The streetcars' classy image and comfortable handling might attract people who wouldn't hop a bus.

The downside is they can get stuck in traffic, slowing the average speed to 9 or 10 mph. All the street activity creates occasional obstacles, in a fast-changing part of town.

During test runs, motorists would suddenly turn, switch lanes or run stop signs in front of the trains, and track grooves have pitched bicyclists onto the street.

Streetcars have stopped for parked delivery trucks that protrude into the trackway; in one case, a train tore off a truck mirror. One train had to wait when a construction lift stalled on the tracks, until workers towed it off. The line makes two tight turns at Thomas Street, making the wheels grumble as the train slows.

To improve travel time on the system, sensors were installed to give streetcars priority over autos at stoplights, even at busy times on Mercer Street.

This is not a high-capacity line, but a local system that lets people avoid a short-hop drive by combining a walk with a train ride, said Jim Graebner, streetcar-committee chairman for the American Public Transit Association. The trackway knits together a neighborhood.

Initial ridership has been projected at 1,000 trips a day, to triple by 2020 as the neighborhood grows.

The streetcar has been opposed by some who consider the city too focused on serving billionaire Paul Allen's Vulcan, the dominant landowner in the corridor; too intent on making the area an upscale enclave; and too willing to see low-rent apartments and small businesses displaced.

"We could use one in South Seattle, in Lake City, in Queen Anne. Any of these could use the streetcar more than the South Lake Union could," said Mike Clauss, waiting for a bus on Westlake.

A sense of anticipation is obvious among others.

"I wish it was here now," Rosemary LeVasseur, who was just transferred to a new Group Health office along the route, said as she walked hurriedly to the downtown post office on her lunch break. She's not pleased about the massive scale of development but said she would ride a streetcar once or twice a week.

Where we're going

Seattle is one of 50 to 60 North American cities to have seriously considered streetcars since Portland launched the most successful of the modern systems, in 2001. Only five or six new systems have been built, because of costs or political delays, Graebner said.

The Federal Transit Administration is trying to encourage new streetcars around the country, through a new grant program called "Small Starts." Some cities, notably Philadelphia, Toronto and San Francisco, have simply kept improving their century-old lines.

South Lake Union's influx of private wealth has allowed Seattle's line to be built without a citywide tax increase or lengthy debate, Graebner said. The city paid for its half of the cost with help from federal grants. But city leaders realize that without fresh funding ideas, or possibly a tax, streetcars will be limited to areas where businesses can pay for it.

There's another price: Streetcar operating subsidies will likely mean that less Metro bus service will be added in Seattle after the end of 2009, when operating costs will shift from the city to Metro. Streetcar ads are expected to cover a share of operating costs.

Advocates hope to extend the South Lake Union line north across the University Bridge, which carried trains in the 1920s. To do that, the city might have to remove parking or road lanes from narrow Eastlake Avenue East, so streetcars could get their own right of way, as they do in Tacoma.

"The trolleys that go in cannot just be toys. They have to have dedicated rail lines to make them dependable," said City Council President Nick Licata, who opposes mixing trains in street traffic.

Another proposed line would be a Sound Transit route from the Chinatown International District to First Hill and Capitol Hill. Money for that line was proposed in last month's regional Roads & Transit ballot measure, which voters rejected.

City officials are also considering streetcars on South Jackson Street to 23rd Avenue South, a route supported strongly by James Kelly, president of the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle. Other routes would reach Seattle Center from the waterfront and Lake Union; travel on First Avenue downtown, or use a revived waterfront route north to Interbay.

Portland's streetcar network has expanded to seven miles and carries 10,000 riders each weekday. "Once you get an acceptable system that everybody likes, it just seems to cascade," Graebner said.

In that spirit, Kelly wants Seattle to rename its fledgling streetcar system the Love Train.

This story includes information from "The Street Railway Era in Seattle" by Leslie Blanchard. Mike Lindblom: 206-515-5631 or mlindblom@seattletimes.com

Opening day

On Wednesday, streetcar service is scheduled to start a bit after noon. Ribbon-cutting is set for 11:30 a.m. at the Westlake Hub, at Westlake Avenue and Olive Way. Rides this month are free.