Couscous: From North Africa and beyond

It was 1973 when cookbook author Paula Wolfert first introduced Westerners to an unfamiliar land of exotic flavors in "Couscous and Other Good Food from Morocco."

Wolfert wrote of bisteeyas and tagines, the dishes that make Moroccan cooking some of the best in the world. But it was on the tiny grains of couscous that she focused much of her attention, with 20 recipes based on her travels and experiments.

Since the book was published, couscous has morphed into a code word for the quick-and-easy dishes that are a staple of many American kitchens. On market shelves, it's common to find an "instant" variety as well as the more traditional Moroccan couscous. The pearl-shaped Middle Eastern couscous from Israel is gaining a higher profile as chefs and consumers discover its chewy texture and affinity for both rustic and refined preparations. And on the pasta aisle, you may find brown paper bags of fregola sarda, also known as Sardinian couscous.

Although all are made from semolina (coarsely ground durum wheat) to which water is added, there are differences in how they are formed. For instance, Moroccan couscous is made by a process of rolling, sieving and drying. Then it's lightly pre-steamed and dried again. Quick-cooking or instant couscous is made by a similar method, but is pre-steamed for a longer time and dried again before packaging. The result is a cooked couscous that tends to be gummy and a little mushy. Although it's less expensive, (Bob's Red Mill brand is $3.99 for a 24-ounce package compared with the Trikona brand of couscous that's $4.49 for a 20-ounce package), it's not the best choice for most recipes.

Moroccan couscous is one of the most versatile ingredients available to us, right in step with our dine-and-dash style. When stirred into boiling liquid, covered and set off the heat for 5 to 10 minutes, it becomes the base for braises or salads. Tossed with herbs and olive oil, it's one of the most uncomplicated side dishes.

The traditional Moroccan couscous meals that Wolfert wrote about (and that are served up at local restaurants such as Mamounia in Capitol Hill and Marrakesh in Belltown) are a more patient undertaking. While each cook has their own method of preparation, it basically goes something like this.

Put Moroccan couscous into the snug-fitting basket of a couscoussiere, or steaming pot, place over simmering broth, cover tightly and steam for 30 minutes. It's then scraped onto a platter and fluffed. Meats and vegetables are put into the broth and fluffed couscous returned to the basket and the covered basket placed back over the top of the simmering broth. Depending on the cook's preferences, the process is repeated once or twice more for about an hour of cooking. The couscous absorbs the fragrant vapors, softening and expanding. Mounded on a platter and surrounded by its fragrant steaming partners, this is a dish that's both sensual and beautiful.

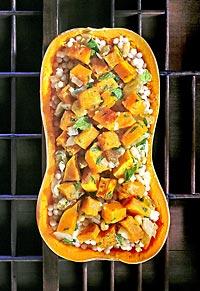

Israeli couscous may be less familiar, but that's part of its charm. Instead of being formed by rolling and sieving, it's extruded and shaped into a tiny pasta that looks similar to pearl tapioca, then lightly toasted to dry. Like pasta, it's simmered in liquid about 8 to 10 minutes. It's delicious when paired with the earthy flavors of mushrooms or roasted butternut squash, and equally at home with more delicate tosses of fresh herbs as a bed for salmon. (The Trikona brand is $6.49 for 16-ounce package.)

Fregola, like couscous, is formed by rubbing coarse semolina and a sprinkling of water into balls, but ones that are coarser and rougher. It's then toasted to a deeper shade of golden brown, which gives it its signature earthy, nutty flavor.

Emily Newman, owner of the small specialty food shop Bella Cosa Foods in the Wallingford neighborhood, stocks fregola sarda from Rustichella d'Abruzzo. (A 17.5-ounce bag is around $7.50.) "It's slow-dried and oven-roasted, with the kind of rustic Italian quality that I like" said Newman. And it cooks in 8 to 10 minutes in broth or water.

While she uses fregola in salads or sides, "it can be used as a substitute in any recipe that uses bulgur or short-grain rice," she said. She composes a favorite salad with fregola, small bocconcini mozzarella balls, chopped tomatoes and grilled fennel. To that she adds a good drizzle of olive oil and a pinch of herb salt. Newman also finds that fregola works beautifully in soups because it holds its texture and shape but still soaks up plenty of flavors. Said Newman, "I love how funky fregola is. Each time [I use it] I seem to stray in a new direction."

CeCe Sullivan: csullivan@seattletimes.com