An Inside Job

HE OWNED a pair of oceanfront lots in Cancun and a cigarette boat he christened "The Outlaw." His dreams shaken by nightmares of being chased by drug-enforcement agents, he planned an escape to the Costa Del Sol in Spain, where he would cat around in his new Mercedes sports car and kick back on four acres of prime real estate — both of which he had acquired from a drug smuggler.

But the agents of his undoing caught up to him, arresting him at his penthouse condo off the coast of Miami, shackling him and shipping him to jail in Western Washington. Brash as ever, he orchestrated another drug deal — from his cell.

On the stand, he lied through his perfect white teeth, believing charm and eloquence could carry him through. When the prosecutor asked if he thought he was pretty smart, he answered, yeah, he thought he was.

The jury saw right through Michael Santos, convicting him as the kingpin of a cocaine-dealing operation that criss-crossed the country from Seattle to Miami. U.S. District Judge Jack Tanner, known in Tacoma as "Maximum Jack," sentenced him to 35 years. At the time — summer, 1988 — Santos was 24 years old. For such a young man, he already had been guilty of many things, arrogance and greed most of all.

He couldn't fathom spending more years in prison than he had been alive. He'd graduated from high school in Shoreline just six years before.

Always the master manipulator, he put his shrewd mind to work: How to redeem himself and earn back his freedom at the same time?

At the Pierce County Jail, awaiting a second sentencing that would get him another 10 years for the jailhouse deal and perjury, he had nothing left but time. In a box of books for inmates, he pulled out a two-volume anthology, "A Treasury of Philosophy." He read the story of the trial of Socrates, identifying with the plight of the intellectual martyr. Although Socrates felt his death sentence from the Athenians was unjust, as was the trial itself, he carried out his own execution by drinking the poison hemlock.

The law's the law, Santos concluded, and he had to accept its harsh judgment. Instead of passing blame, he would take it.

"I needed to find a way to make the defining moment of my life what I would accomplish through my imprisonment instead of what I had just put everybody through," Santos recalled recently. "I remember saying to myself, 'Write to the newspaper, say what you are going to do so that some day you can be held accountable and can look back and say you've done it.' "

IN PENCIL, Santos wrote a letter from jail and addressed it to me, the Tacoma News Tribune reporter who had covered his trial. In hopes of a reduced sentence, he wanted a public platform for announcing his plan for redemption.

The front page of the June 27, 1988, paper featured a photo of Santos, cross-armed, dressed in a jail-issue blue jumper, shirt sleeves rolled up to expose his biceps. "Take it from a convicted pro," the headline read, "Drug dealing is a losing proposition." Santos' plan was to dissuade others from getting into the drug trade.

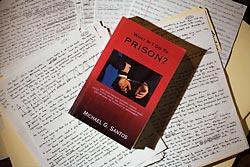

While he has not followed that exact path, Santos has made the most of his time inside. While serving in six different federal prisons, he has earned bachelor's and master's degrees, and authored four non-fiction books that expose prison life. His most recent, "Inside: Life Behind Bars in America," released in August by a major New York publisher, is targeted to a general audience. Through personal observations and interviews with other prisoners, Santos uses graphic details and language to hammer home his point that federal prison is a viper pit that promotes retribution at the expense of rehabilitation.

Criminal-justice and social-work professors have assigned Santos' books as texts and consider him an objective authority on life inside from someone on the inside. His wife, a Shorecrest High School classmate he wed in prison in 2003, maintains the Web site www.michaelsantos.net, in which Santos reports quarterly on his progress toward redemption. His mandatory release date, which reflects time off for good behavior and parole, isn't until August 2013. He will be 49 years old.

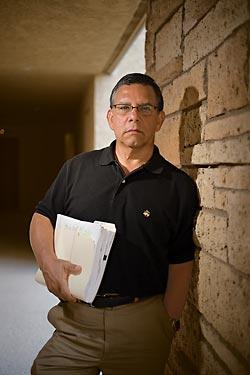

Eighteen years after interviewing Santos in the Pierce County Jail, I met him again, this time at the U.S. Penitentiary in Lompoc, Calif., where he is incarcerated at a satellite work camp with barracks instead of cells and no security fence. He had written me, requesting that I review "Inside" for The Seattle Times.

All things considered, Santos looks good for a 42-year-old. He runs eight to 12 miles, two or three days a week, and carries earplugs in his pocket to drown out the defeatist drone of prison life. To the interview, he wears an olive green shirt with prisoner number 16377-004 embroidered on it. The camp administrator has granted us a couple hours to talk privately inside a meeting room near his office. Not all who request a meeting with Santos get one.

"We call this a system of corrections," Santos tells me. "By definition, it would seem that the system would encourage growth. I have not found that to be the case. The prison administration does not recognize the formal efforts that I have made for so many years. I am treated no differently than a man who watches television or plays cards all day."

Sam Torres, a federal probation officer for 24 years before becoming a professor in the criminal-justice department at California State University-Long Beach, also has asked to meet Santos in prison. He is impressed with how Santos realistically describes the coarse prison environment and has assigned Santos' books in his classes. His students send questions to Santos, which he answers in often lengthy replies.

"You have to be very careful with prisoner-written books," Torres says. "They tend to have an ax to grind and amplify the negative. I know the convict mentality, the B.S. prisoners can throw out for their own interests. Michael Santos is bright, talented and wanting to help. My sense is the guy is as genuine as genuine can be."

The Federal Bureau of Prisons has denied the professor's request to meet with the prisoner, saying it is not in the best interest of the institution, according to Torres. "The logic escapes me," he says, and Santos concurs, saying Torres is exactly the kind of mentor he needs to help prepare him for life on the outside.

"It's not a surprise to me that so few emerge from prison successfully," Santos says. "I find it incredibly disturbing that if I tell an administrator I'm looking to prepare for my future, they say, 'Well, you've got seven or eight years to go, what are you worried about that for? You've got to get closer to the door.' "

Already, Santos has served more prison time than many pedophiles, rapists and murderers. His sentence came at the height of the drug wars, when Nancy Reagan urged young people to "just say no." University of Maryland basketball star Len Bias had just died of a cocaine overdose. Gang violence and crack cocaine had taken over an inner-city Tacoma neighborhood.

"Would I advocate for the same sentence today? No, I wouldn't," says Portia Moore, a former assistant U.S. attorney who helped prosecute Santos. "But at the time, it was appropriate. He was considered a major player, and he played the part of drug dealer to the max. He flaunted it in our faces. He dealt from jail. He showed no remorse at all."

Santos says he cried when Bill Clinton was inaugurated, believing the Democrat would reward his hard work in prison by commuting his sentence. But Clinton denied Santos' request, and although a similar petition is pending before President Bush, Santos has no expectation that it will be granted.

Torres, whose parolees and probationers used to call "Send 'em Back Sam," has written letters endorsing Santos' early release. "I'm no liberal about these things, but I cringe at knowing we are warehousing him for no good reason. He poses absolutely no danger to the community."

HIS SHORECREST classmates called him Mike, but he wanted to be addressed as Michael because it sounded more sophisticated, more adult. He dressed the part, too, wearing Giorgio Armani sweaters instead of Russell Athletic sweatshirts.

A shy girl at Shorecrest tried to avoid him and his group of friends. "These were not nice boys," she recalls. The two shared an awkward kiss at "Senior Spree," but it was no big deal.

After high school, he took over the business side of an electrical-contracting company founded by his father, a Cuban immigrant who raised his family in Lake Forest Park. The younger Santos had a plan to grow his father's modest but successful company into a major player, but his grandiose ideas ran the business into the ground. Abandoning the mess he created, he turned to the easy money of cocaine.

The shy girl heard about his trial and his sentence, but didn't pay much attention. At the 10-year reunion, people made jokes about him being locked up for a long, long time.

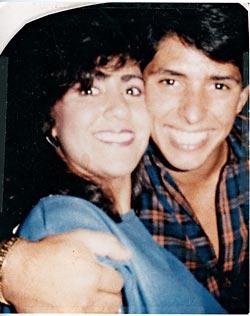

She married, had two kids, divorced, remarried and divorced again. While planning the 20-year reunion in 2002, she received an e-mail asking if it was the same Shorecrest that Michael Santos attended. "Friend or foe?" she asked. "Friend," the e-mailer replied, and informed her about Santos' Web site. She took one look and was captivated by Santos' photo. "He looked so healthy and so peaceful."

She wrote him an 18-page letter that night. "Dear Mike," it began. "You used to know me as Carole Goodwin."

And so began an intense correspondence. She lectured him about character, integrity and the evils of drugs. He filled her in on his life, his work and his methods for emotionally surviving prison. He ranked the 10 most important values in his life and explained what he was doing to live up to each one. "Wow, that's not the Mike I remember," she thought. She had so many questions. He had so many answers. "I felt free to tell him things I wouldn't tell anyone else. He opened my mind in ways I never knew possible."

Thousands of pages and a few phone calls later, he proposed to her in writing. They wed in June 2003 in the federal prison at Fort Dix, N.J., their marriage license describing him as a resident there. No flowers were allowed inside. They shared a wedding kiss, which is about as passionate as it gets for them even to this day, as conjugal visits are barred.

Carole Santos, who is studying to be a nurse, now lives with her teenage daughter in a tiny $1,000-a-month apartment in downtown Santa Barbara. The living room triples as Carole Santos' bedroom and office, where she dutifully works as her husband's liaison, transcribing his writings from longhand to type, sorting his correspondence and managing his Web site.

"I am his link to the outside world," Carole Santos says.

Nearly every Saturday and Sunday morning, she makes the hour drive north to Lompoc, arriving just before 8:30. They sit within a prison camp garden flanked by tall eucalyptus trees, share vanilla lattes from a vending machine and talk about her schooling, her children, his writing, his Web site, their goals, their romance.

SANTOS HAS OVERCOME obstacles through an extended network of supporters — academicians whose mentorships he aggressively pursued, a wife who never doubts him, a warden who encouraged him, a sister who never gave up on him and a co-defendant who testified against him.

Colin Harris, a Mercer University professor of religious studies, taught undergraduate philosophy courses to Santos at the penitentiary in Atlanta in the early 1990s.

"What made Michael stand out was his eagerness to soak up every ounce of educational opportunity he had," Harris says. "He was able to say, 'This place is not going to define who I am,' and in doing so, served other prisoners as an example of courage and dignity."

Dressed in cap and gown, Santos gave the commencement speech as valedictorian of his prison class.

"His message was to choose your goals and commit yourself to them, and to not let anything keep you from doing that," Harris recalls. "From that setting, the message carried more authenticity than it would from others."

Julie Santos, Michael's older sister, also attended the ceremony at the penitentiary and recalls a second speech by the instructor of an ESL class who implored her graduates to "Be Like Mike."

"My brother accomplishes more in prison than anyone who is free," she says from her Ballard home. "And he has a better attitude than anyone I know."

She secured a $20,000 grant from King County and DARE to help get her brother's first book published. It was printed for free at the family business of one of Santos' co-defendants, a Shorecrest friend who got arrested with a kilogram of cocaine in the trunk of his Porsche and then testified against Santos as part of a plea bargain. He served 32 months in a federal prison camp and has been free since 1989.

While others in the cocaine ring made deals with the government, Santos brought in a Miami attorney with shiny hair, shiny shoes and a shiny suit who had represented the Trafficante mobster family and was a member of Patty Hearst's defense team with F. Lee Bailey. Santos says the lawyer told him he could beat the rap, and Santos was just conceited enough to believe him. The defendant who likened himself to Scarface was acting as if he was on "Miami Vice."

Santos says he feels no anger toward those who testified against him and has no one to blame for his fate but himself. "When you are facing 20 years in prison, I think it's normal to pursue the course of self-preservation. We all made our choices. Mine happened to be a really bad one."

The co-defendant sends Santos' wife a check for $100 to $150 each month to help with the Web site — not out of guilt, he says, but out of respect for what Santos has accomplished. He pleaded to keep his name out of this story, even though his conviction is public record. He wants to protect his family, particularly his two young daughters, from the stigma attached to a convicted drug dealer.

THROUGH DOGGED PURSUIT, Santos found a New York-based literary agent for "Inside." A good one, too, as it took only about three weeks to secure a deal with St. Martin's Press.

Before "Inside" even hit the book stores, Sony Pictures inquired about buying the TV and film rights. Santos also has finished a draft of his first novel, "Clean Money," an adventure story set in prison about a Seattle money launderer who exacts retribution against all who wronged him. Santos describes it as a cross between "The Shawshank Redemption" and "The Count of Monte Cristo."

Michael Santos has made it his business to be launched when he is sprung. It doesn't take much to imagine the telegenic former prisoner, his teeth still perfect, making the rounds on the talk-show circuit, or serving as an expert commentator on Court TV. Next on "Oprah": the Michael Santos story.

"Inside" could earn Santos a lot of money, but federal law prohibits him from profiting off his crimes. He has gotten around the rule by giving the manuscript to sister Julie, who now owns it. If she chooses to set aside the proceeds for her brother for when he is released, that's her prerogative.

On his Web site, Santos gets a fair share of e-mails from the unmoved, who think his punishment fits his crime. They see Santos' story of redemption as just another manipulation by the master himself.

They're as cynical about the system as he is.

To those who question his sincerity, he points to his achievements and poses a question of his own:

"I'm not going to feel embarrassed for what I've done while I've been in prison. If people have a problem with that, I'm curious: What am I supposed to do?"

Stuart Eskenazi is a Seattle Times staff reporter. Benjamin Benschneider is a Pacific Northwest magazine staff photographer.