What it means to be human in a clone's world

"Science is always wrong," wrote George Bernard Shaw. "It never solves a problem without creating 10 more."

Even if he exaggerated for witty effect, Shaw was clearly on to something. No one knows that better than leading British playwright Caryl Churchill, whose recent drama "A Number" gauges the ripple effects of a scientific breakthrough on the lives of one man and his offspring.

Sensitively and cogently directed by John Kazanjian in its Seattle debut at ACT Theatre, the play is slender in size (it runs barely an hour). But it is capacious in scope and resonance.

Tenderly, unsparingly and with mordant slashes of humor, Churchill does nothing less than ponder what it means to be a father, a son, a person — in an age when advancements in reproductive biology challenge our basic assumptions of humanness.

With a trenchant poetic minimalism that can't help but bring to mind the plays of Pinter and Beckett, "A Number" sweeps us into a not-too-distant future of so-called "DNA technology."

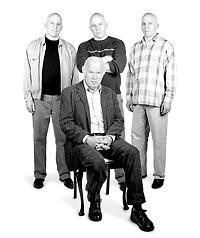

In the first of several scenes, Salter (Kevin Tighe) and his adult son Bernard (Peter Crook) confront the astonishing news that they've been unwitting players in a cloning experiment. It seems the same genetic material was used to create multiple, physically identical people.

The discovery triggers more secrets, lies and their ramifications, which Churchill brilliantly uncoils.

What were the exact circumstances of Bernard's parentage and birth? What really happened to the mother he never knew? Are the strangers who share Bernard's genetic material his brothers and Salter's sons? Or is there some new breed of relation, not yet defined or named?

What is revealed at first is challenged later, in Salter's encounters with two Bernard look-alikes (also played by Crook).

The striking personality differences among the three men refute the fear that cloning will produce wholly identical people, but plunge us into the complex debate about nature vs. nurture.

It's best not to give away the shattering revelations "A Number" unwraps.

But there is not a whiff of melodrama here. In fact, Churchill's script is a master class in how deep and resonant a lean, sinewy script can be. As Salter and the others grapple for language to describe the unimaginable, every word counts. Nothing is wasted. And anything said may come back to haunt you later.

On opening night, the two-man cast had not yet fully mastered the stop-and-go rhythms of Churchill's often fragmentary dialogue. There were a few flubs in what is essentially a syncopated musical score for two voices.

But the rough spots will surely iron out. And otherwise, Tighe and Crook are right in tune with their roles and Kazanjian's spare production.

Like shadows on a craggy outcrop of rock, bafflement, guilt and grief play across Tighe's features as he absorbs unwelcome truths. And Crook, skilled as ever, gives his three roles the individuality they must have.

In length "A Number" may seem slight. But like other great Churchill plays ("Top Girls," "Cloud Nine") it brings big social and existential concerns down to human scale — so they can hit us right where we live.

Misha Berson: mberson@seattletimes.com

Theater review

"A Number," by Caryl Churchill, Tuesdays-Sundays through Oct. 1 at ACT Theatre, 700 Union St., Seattle; $10-$54 (206-292-7676 or www.acttheatre.org).