Batman, Spider-man — why not SuperJew?

It's not set in tablets of stone, but it is a reasonably good rule of thumb: Goldman, Friedman, Superman, Batman ... if a name ends in " — man," we're probably talking about either a Jew or a superhero.

The connections linking these two groups are strong, and they date back thousands of years. Think the Incredible Hulk is modern? Think again, boychik.

Since Biblical times, Jews have embraced the legend of Golems, immensely strong but malleable creatures formed from clay or other inanimate stuff. A Golem could be summoned in times of trouble, then dismissed when not needed. Not unlike the Hulk.

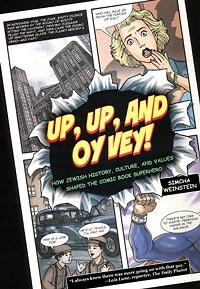

As a nice Jewish boy growing up on Mercer Island, reading comics like crazy (and wishing desperately for my own superpowers), I could half-intuit such connections, but they were never explicit. So it's very cool to see them quantified in Simcha Weinstein's funny, illuminating and brilliantly titled "Up, Up, and Oy Vey! How Jewish History, Culture, and Values Shaped the Comic Book Superhero" (Leviathan, 150 pp., $19.95).

Sometimes the links are serious. Jews, for instance, love wrestling with the same hefty issues that obsess your average superhero: being outsiders, not fitting in, assimilating, making new lives in strange lands. (Not to mention your basic eternal struggle between good and evil — always a favorite.)

But hey — these are comic books! They're also fun!

And so Weinstein, a British-born rabbi and comic-book nut, has a great time outlining the offbeat ways in which comics and the comic industry are steeped in Jewishness.

Beginning in the genre's Golden Era — roughly the 1930s through the 1960s — most of the heavy hitters in comics have been Jews. Early on, they shaped the industry's parameters of art, philosophy, morality and business.

One famous example: Superman, invented during the Depression by two Cleveland teenagers, Jerry Siegal and Joe Shuster. Superman (as everyone on the planet surely knows) went on to become the superhero's superhero, the blueprint for all future good guys and currently the subject of a big cinematic comeback.

Siegal and Shuster filled Superman's story with all sorts of rich Jewish themes. Take, for example, his origins: As an infant, he was rocketed to safety away from his doomed planet. Yo, Moses!

(In 2000, by the way, novelist Michael Chabon used Siegal and Shuster's real-life story as a base for his brilliant Pulitzer Prize-winner, "The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay.")

The examples go on and on. There's Jack Kirby and Stan Lee (born Jacob Kurtzberg and Stanley Lieber), the masterminds behind Marvel Comics and such immortal characters as Captain America, Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four and X-Men. As with Superman, their stories were layered with themes of bigotry, patriotism, assimilation and otherness — not issues exclusive to Jews, of course, but ones that were (and are) of special concern to them.

The references go on as well. Bad-guy mutant Magneto is a Holocaust survivor. Captain America fought Nazis. The supremely grumpy Thing is overtly Jewish. (So is Sabra, a hectoring Israeli superhero who's appeared in Hulk and X-Men stories.)

And, in a story from 2006, Superman attended Sabbath dinner at the home of a Jewish reporter. (Grape juice was served; the Man of Steel doesn't drink.)

Then there's Leo Zelinsky, the New York tailor who's been making superhero costumes for decades. Who knew? Turns out he outfitted the Thing with extra-big pants, fixed Thor's cape and even (in a moment of impartiality) helped clothe arch-villain Dr. Doom.

Zelinsky typifies the dry humor and pragmatism common to both Jewish and superhero culture. After mocking Spider-Man's outfit ("No weather-proofing, no proper ventilation. ... You could get athlete's foot all over your body in a thing like this"), the tailor leaves him a sketch: "You ever need a look like this, you come see me. I'll give you a good price."

But what of my own superpowers, you ask? Well, when I hear someone has the flu, I channel my Jewish grandmothers — or at least the one who could cook — and make chicken soup. I'm told it has certain restorative powers, and I try to use that power for good, not for evil. It's an awesome responsibility.

Adam Woog is a frequent books contributor to The Seattle Times: awoog@qwest.net