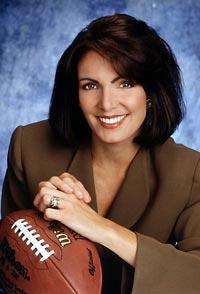

Visser to be honored at Hall of Fame ceremonies

BOCA RATON, Fla. — The message greets Lesley Visser every time she sits at her computer.

Scribbled on the back of a restaurant menu, now protected by a frame, it hangs on a wall in the corner of her home office, amid a mass of photographs and newspaper clippings.

Six words, from one pioneer to another.

"Champions adjust. Pressure is a privilege — BJK"

"BJK" is Billie Jean King, the female tennis player who famously beat Bobby Riggs in 1973.

Visser calls King an idol. And Visser needed one when, like King, she built a bridge across the gender gap — hers by entering the male-dominated world of sportswriting in 1974.

Visser, then at The Boston Globe, was the first female NFL beat writer. Then a network television sports reporter. And this weekend, she'll be the first woman to receive the Pro Football Hall of Fame's Pete Rozelle Radio-Television Award, perhaps the most prestigious honor in her trailblazing career.

For it, she'll be celebrated at a Hall of Fame dinner in Canton, Ohio, while Troy Aikman, Warren Moon and others will be enshrined.

"We were officially going as Troy's guests," Visser, 52, said of herself and husband Dick Stockton, a sportscaster for Fox. "Now I'm going in with him!"

Visser knows she's a trailblazer. The hundreds of congratulatory e-mails tell her so.

But that's not what she set out to be. An avid Red Sox and Celtics fan during her childhood in Quincy, Mass., Visser just wanted to talk about sports.

She never imagined so many people would talk about her.

In 1974, Visser dared to walk into The Boston Globe's newsroom as an intern — and one of the first women to enter sports journalism.

Within two years, The Globe tabbed her as one of its two Patriots beat writers.

It was a solid business move — "Her talent was fairly obvious," then-Globe sports editor Vince Doria said — but a bold one in a time when media credentials bore the phrase, "No women or children allowed in the press box."

The first year, Visser said, was a "migraine headache."

She faced more than just the grind of an NFL beat. With no ladies' room in the press box, she made strategic pit stops at the public restrooms downstairs.

All the while, various media outlets were sending reporters to write about The First Woman. But Visser never wavered.

"I've never known her to be overwhelmed by anything," said Mike Lupica, a New York Daily News sports columnist who attended Boston College with Visser. "She just soldiered on with her talent and immense charm, and she acted like she'd been there before."

Now, 30 years later, Visser is known as the first almost everything — in addition to her NFL beat, she was the first woman to appear on ABC's "Monday Night Football," the first to cover a Super Bowl from the sidelines and the first and only woman to present the Lombardi Trophy.

But her journey wasn't exactly a walk in Fenway Park.

The New York Giants game was over, and Visser and Christine Brennan, then with The Washington Post, wanted to interview stars Phil Simms and Lawrence Taylor.

But the year was 1984, and while some locker rooms were open to women, the Giants' wasn't. So Visser and Brennan were told to stand in the weight room.

"Or is it the wait room?" Visser quipped.

After waiting and waiting, a Giants offensive lineman walked in. His jersey, still on, was spotless.

Brennan recalls Visser saying, " 'This is not funny! We are two professionals, and they just brought us, as our first person to interview, a man who did not play in the game.' And I said, 'You're right. This is not funny.' And you knew things had to change."

The next year, Rozelle, then the commissioner, mandated that all teams allow female reporters into locker rooms.

Colleagues say Visser connects with athletes and coaches alike. She treats them with respect, and they return it. Her bright sense of humor disarms even the most closed-off sports figure.

"People like her," sportscaster and longtime friend Hank Goldberg said. "The biggest names in sports [are] willing to talk to her."

Often, these interviews turn into friendships. Visser emceed former quarterback Steve Young's retirement party. She spoke at a charity function hosted by Yankees manager Joe Torre. She even has a framed letter from the legendary — and media-despising — coach Bob Knight.

In 1984, CBS told Visser it wanted a woman sportscaster. But instead of teaching sports to a TV person, the network decided to teach TV to a sports person.

So it offered Visser the job. And she almost said no.

"They were like: 'What are you, nuts? We're offering you a network job!' " she said with a laugh. "And I was like, 'But I have the greatest job.' "

She ended up splitting time between CBS and The Globe, but that only lasted until 1987. As much as she loved sportswriting, she saw TV as an even bigger passport — a way to let sports take her anywhere.

While at CBS, Visser covered Final Fours, Triple Crowns and U.S. Opens. She even covered the fall of the Berlin Wall from a sports perspective.

But football took priority. When CBS lost its NFL contract in 1994, Visser left for ABC and ESPN. Four years later she took the "Monday Night Football" sideline spot.

She returned to CBS in 2000. Though her reputation is carved mostly in broadcasting — the Rozelle Award is for television and radio work — she never lost her passion for the printed word.

"She's always regarded herself as a writer first," Stockton said.

When the girls went out on Halloween, some dressed as ballerinas. Others dressed as Mary Poppins.

One went as Celtics star Sam Jones.

That was a young Visser, who played three sports in her youth and loved following them even more.

That didn't change when she joined The Globe. It didn't change when she went to CBS. Even today, she said, when she goes to Lambeau Field or Soldier Field, she still gets that special feeling.

"I really never, ever, for one minute, [was] into the fame or the money," Visser said. "I was always into it because I loved the sports.

"Truthfully, my happiness quotient was no different when I was going to the Final Four for The Globe, making $25,000, than when I was going to the Final Four for CBS. My happiness [came from] the privilege of being at the Final Four."

Such a privilege has given her quite a life — a "billion-dollar life," she calls it — complete with stories, experiences and a wealth of help from friends and her parents, Max and Mary.

It hasn't been perfect, with all the problems and the pressure. Being the first, she said, is both "a burden and a blessing."

But mostly a blessing.

That's because, when it comes down to it, Visser knows two things:

She really loves sports.

And pressure is a privilege.