Fear Of Flying

AS UNITED AIRLINES Capt. Jim Dunn arrived at San Francisco International Airport in mid-April 2001 for a meeting with the flight attendants of UA 857, he had no idea he was about to have a very bad day.

Dunn, whose wide-open face reflects the confidence gained over 35 years in both military and civilian aviation, sat down and took off his hat. He was in a good mood. Several of the flight attendants were acquaintances, and he liked them. In the back of the room stood his friend, Mark Sancya, a United captain wearing civilian clothes. Outside, it was 54 degrees with fairly clear skies — good conditions for flying.

Dunn's attendance at the meeting was an anomaly for an airline captain at the top of his profession. In the rarified circle of 747 captains, it is a social faux pas to attend such meetings. Dunn, whose mother was the backbone of his upbringing as his pipe-fitter father moved the family from town to town, sees things differently. Attending the pre-flight meeting was his way of showing solidarity with his crew.

Once aboard the plane, Dunn sipped a latte as he ran through his cockpit checklists. He monitored his co-pilot, a captain-in-training, who taxied the double-decker behemoth to runway 28-Right, pushed the throttles forward, and took the plane aloft onto its long, arching trajectory toward Shanghai.

It was about five hours later when, somewhere near the Aleutian Islands, Dunn was urgently summoned downstairs to the main cabin. Two young women were fighting; one had given a flight attendant a bloody nose, and passengers were scared.

Dunn arrived at Row 56 near the back of the plane to find a pair of identical twins — auburn-haired models, 22 years old — huddled against a dark window. "We're not doing anything wrong," Cindy Mikula pronounced with a slight slur. "We're just going to Shanghai for a modeling contest."

Playing the conciliator, Dunn guided the twins to business class, settled them in under a blanket, and left.

But within moments Cindy was running down the aisle and screaming. Dunn rushed to the tail of the plane in time to see her slam a phone against the wall, the sound cracking the air like a shotgun blast, then grab a door on the side of the plane and try to open it. There is no way she could have — a cockpit-controlled security system makes sure of that — but trying to is against the law.

Dunn reached into his back pocket and handed a pair of plastic handcuffs to Sancya, who had been traveling as a passenger and was now on the scene. "Would you do me the honor?" Dunn asked.

Flight attendants restrained Cindy's twin, Crystal, as she tried to free her sister, and Dunn went back to flying the plane. Down in the cabin, the passengers looked up at the movie screens and watched as the red line showing their progress to China slowly became a boomerang. Concerned about flight safety and wanting the twins arrested on U.S. soil, Dunn had turned the plane back to Alaska in the darkening evening sky.

"Well, I guess this is what you'd call 'gettin' Shanghaied,' " a passenger said, the moment captured on another passenger's video camera.

AS THE FIASCO of Flight 857 made worldwide headlines, Dunn delivered his waylaid passengers to Shanghai and began leaving phone messages with United headquarters in Chicago. The tools from his emergency-situation training — known in United jargon as Command Leadership and Resource, or CLR — did not work.

But no one called back. After more fruitless calls, he gave up and sent an e-mail to the vice president of flight operations:

. . . Outside of the immediate crew and help from Capt. Dave Laubham, it appears as though no one really gives a rat's ass about what took place . . . This is a safety issue, and it is the proper time for the folks making the big bucks to step forward and do their jobs.

Dunn thought his e-mail, sent with the title "Sex" to get the VP's attention, and the $200,000 it cost to divert the plane would spark at least a phone call. But he didn't hear from anyone for nearly two weeks, and then it was a hostile junior executive asking him just what was he trying to accomplish.

For Dunn, the airline's handling of the situation represented another major blunder in a commercial-airline industry that had been in steep decline for more than 20 years. Before the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978, the industry operated under the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB), which set fares and limited new carriers from entering the market. Four airlines dominated the domestic skies: American, Eastern, United and TWA, while Pam Am controlled the international routes. The system was by no means perfect — historians estimate the industry lost more than $1 billion during several decades of CAB rule — but no major airline went bankrupt, and customer service was a top priority. With little concern about a price war, carriers focused on porcelain plates, silverware, free alcohol, plenty of smiles and great routes to lure customers.

For a few years after deregulation, the future looked bright. New airlines rapidly sprang up, and ticket prices declined, just as economists had predicted. Then a confluence of crippling factors — high fuel costs due to an oil crisis, skyrocketing interest rates and a subsequent recession — put the industry into a stall. And while the deregulation act had dealt with the number of flights and how much they cost, it had not covered the hefty costs of labor, equipment and maintenance, all of which were rising. Braniff was the first major airline to fall, filing for bankruptcy in 1982.

Only a few airlines were expected to go under. But a loophole in U.S. bankruptcy laws allowed airlines to break their union contracts while in Chapter 11, and the fate of the industry was sealed. Continental boss Frank Lorenzo jumped through the loophole in 1983. He filed for bankruptcy, then fired every employee and hired a third of them back on his own terms. He soon followed a similar path with Eastern. Eventually, the union loophole was altered, but it was too late. The bankrupt carriers — free of the profit standards the other airlines faced — dropped their fares, undercut the competition and controlled the economics of the industry from the bottom.

The news wasn't all bad. From 1977 to 1992, domestic fares dropped by a third, saving consumers billions. But nearly every major domestic airline, United included, eventually filed for bankruptcy. As each one slid toward receivership, service was pulled from many cities. Passengers started driving hundreds of miles to catch a good flight. Crew salaries were slashed. Strikes ensued; pilots walked off planes in front of live cameras.

Inside airports, crews were pruned, and ticket lines grew. Inside cabins, dinners on many flights shrank from three-courses-plus-dessert to peanuts. American infamously removed one olive from each of its first-class and business-class salads. Eventually, passengers on all major airlines were charged for nearly everything, even headphones.

All the while, airlines were setting tighter turn-around times and overbooking flights; planes were packed.

It was into this environment that Dunn flew in April 2001 with the Mikula twins. The captain certainly knew what was going on. Twice he'd been furloughed because of budget cuts. Nevertheless, before Flight 857 his spirits remained high. United had always welcomed him back with good flights and more money.

But Flight 857 changed things. Perhaps he was OK in the cockpit, but the flight attendants were increasingly at risk, especially as aggression was growing in nearly all corners of society. The airline culture of convenience and friendly service had been replaced with a culture of compromised crews and frustrated passengers. Dunn knew he could not fix all of this, but perhaps he could at least figure out a way to protect those who depended on him once the wheels left the tarmac.

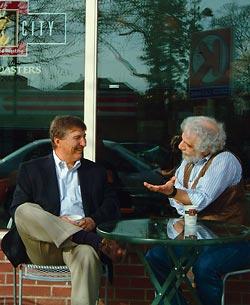

CAPTAIN DUNN MET Zak Schwartz for the first time at a coffee shop in their hometown of Eugene, Ore. Dunn's daughter had suggested they get together. A psychologist known for his effective interventions and books on dealing with anger, Schwartz wanted to know how Dunn had handled the Mikula twins.

"Did you split them up?" he asked.

"No."

"Were you able to communicate with them?"

"Yeah, they told me at one point to screw off."

"Well, that's communication. Did you corner them in any way?"

"Yes."

"You can't do that, they need a way out."

Schwartz explained that his approach to counseling is built on five major interpersonal rights, including the right to feel safe. Anger is the human response to vulnerability, so the key to defusing it is to figure out why someone is feeling vulnerable.

Schwartz emphasized that his techniques could be applied to the drunk, the drugged, the crazy and the confused. Less New Age naiveté than practical intervention, they were based on 25 years of refinement in rock concerts, prisons and other volatile environments. The techniques, Dunn realized, went far beyond United's training.

The men discussed the fact that cursing, yelling and swinging at flight crews was becoming more common. Between 1995 and 2000, FAA data showed a steep increase in unruly passenger incidents. While there was no definitive number of these incidents — many are never reported, federal files represent only those cases in which civil penalties or warnings are issued, and many incidents disappear into the files of port authorities and various police agencies — there were hundreds of incidents every year, and perhaps thousands, in a country with 2 million daily commercial air passengers.

Dunn and Schwartz agreed to outline a response program that would "train the trainers." Dunn also returned to his computer, firing off e-mails to United officials, who continued to ignore him. Some of his crew members joined the effort. Still, nothing.

Then, on June 21, 2001, the company issued an internal memo announcing cutbacks to the CLR program; "too costly."

Not three months later, the unthinkable: 9/11. Aggressive anti-terrorist policies were stirred into the already volatile mix. Flight attendants, alone with passengers once pilots locked themselves behind cockpit doors, took karate lessons and screamed at the drunk and stubborn. On a Northwest flight, the crew had an otherwise well-behaved man arrested after he refused to return to his seat.

Recognizing these new complications, Dunn and Schwartz pressed on, forming a company called Plane Reaction and pitching the airlines to consider its training program. Several seemed interested, but none took action. So, Dunn and Schwartz hit the speaking circuit. At the World Aviation Conference and Trade Show in Montreal in May 2003, the men for the first time detailed their program to 200 flight attendants and airline executives, presenting an argument that airlines can save money and prevent costly diversions by augmenting what was left of existing programs. The response seemed enthusiastic; a few airline executives even gave Dunn and Schwartz business cards. Then, nothing.

What the men didn't quite comprehend at the time was that they were wading into a political and economic miasma thicker than a February fog at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. The airlines were bleeding billions — more than they had pre-9/11. The FAA and the Transportation Security Administration were struggling over which agency would define and enforce the rules for in-flight security.

Behind the scenes, several airlines were, in the name of cost-cutting, lobbying Congress to limit requirements on additional safety and security training for flight attendants. They succeeded in 2003 when language in the FAA reauthorization bill under discussion in a late-night conference committee was changed to say airlines may require advanced training for flight attendants instead of saying they must require it. Flight attendants now receive an average of two hours of refresher training on safety and security each year, most of it related to flight safety or terrorism, not unruly passengers. One airline offers 15 minutes of annual karate lessons.

For their part, United and the other major airlines say they are not limiting customer-service programs out of spite or ignorance. They say passengers have consistently proven they are driven by one thing — price — and no matter how much service declines, passengers continue to fly. In fact, they continue to fly in ever-increasing numbers.

Industry analysts agree that passenger numbers are up, especially on low-price airlines such as Southwest. The airline is the only major U.S. carrier that has consistently made money in the past 20 years. They did it by limiting in-flight frills and ditching the old hub-and-spoke route model. Jet Blue is a similar no-frills darling of the industry. So, in effect, United and the other airlines are arguing that passengers themselves have created the new bare-bones service model by constantly choosing the lowest price.

Dunn and Schwartz say the airlines are moving in the wrong direction. United, they say, has even diverted planes over relatively small incidents. It diverted one recent flight to handle a drunken passenger, then sued the man for the cost of the diversion. In January, it made an emergency landing in Salt Lake City when a woman started yelling at passengers and harassing the crew on a flight from Eugene to Denver. Passengers say the woman was behaving oddly when she got on the flight, but no one took action. The woman was charged with a felony, interfering with a flight crew.

After 9/11, Dunn predicted it was only a matter of time before the airlines' hard line, limited training and more air marshals led to the death of a non-terrorist passenger. He was proven correct this past December when an air marshal shot a mentally ill man, Rigoberto Alpizar, traveling on American Airlines in Miami.

After the shooting, Dunn sat in his favorite wooden chair and fired off e-mails to some of America's leading news organizations. He said he didn't think the air marshal in Miami made a mistake; he did what he was trained to do. Perhaps there could have been a different outcome, he wrote, with different training. Perhaps the flight attendants and air marshals might have identified the man's illness earlier and had health-care workers waiting for him when the plane touched down. There was no response to Dunn's messages. He wrote directly to American Airlines, making the same arguments. He received a brief form letter thanking him for his interest in the airline.

Today, Dunn and Schwartz have come to a crossroads. They are neither speaking publicly nor consulting. Flying all around the country and getting nowhere has taken its toll. The men still meet at the Eugene coffee shop where they first chatted, and hope someone will call. In the meantime, the airlines continue their descent. The Bureau of Transportation Statistics says they've lost approximately $41.7 billion since 9/11.

FAA numbers show that as passengers returned to the air after 9/11, so have in-flight disturbances. None of those disturbances has been related to terrorist activity since the "shoe bomber" in December 2001.

Nothing less than a complete shift in the economics of the airline industry is likely to help Plane Reaction get off the ground, much less bring back a world of top-notch passenger service. Congress isn't helping. U.S. Rep. Peter DeFazio, an Oregon Democrat who serves on the House aviation subcommittee, says plenty of ideas have been floated around Congress, including a European-style subsidy system. But mostly, he says, the ideas are laughed at.

And the truth is, even the world's most heavily subsidized airlines lose money. In Europe, the industry is looked at as an engine of commerce, not a profit machine.

So in this country it boils down to choices and priorities — the industry's, the customers', the government's. For now, America's horizon lines are open to the lowest bidder. Airlines are considering charging for soft drinks. Northwest is testing a $15 fee to reserve certain premium seats, and crew members recently voted to reject further pay cuts. Contract negotiations continue.

Seth Clark Walker is the program coordinator of the University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication Turnbull Portland Center. He was recently named a Literary Arts Fellow in Oregon.