The evolution of ceramist Akio Takamori

As the new exhibitions of Japanese-born Seattle ceramic sculptor Akio Takamori make clear, he is an artist with two consecutive, but related, artistic lives: potter and sculptor. His two current shows demonstrate the differences between the two.

At the Tacoma Art Museum, "Between Clouds of Memory: The Ceramic Art of Akio Takamori" is split between large decorated pots and free-standing figurative sculptures. In the Henry Art Gallery's "Akio Takamori: The Laughing Monks," only four sculptures are on view, but the artist has augmented the display by selecting from the permanent collection 29 pots and 14 prints and photographs by other people. The results are a giant summer picnic of historic and contemporary ceramics.

Professor of art at the University of Washington since 1993, Takamori, 56, came to ceramics the hard way. After college in Japan, he apprenticed with a master potter for two years of grueling and menial work. Discovered in Japan by a Kansas City Art Institute teacher, he was offered a scholarship, came to the United States, and followed that up with another at Alfred University, America's first college-based clay program.

Visitors to Tacoma will see the first decade of his unusual decorated pots, along with the free-standing sculptures. Simple schematic figures in cartoonish settings, male and female nudes are joined on the sides of the pots by animals and birds. The works are representative of the artist's struggle to make the pots themselves into successful sculptures, which dates back to the 1980s when Takamori was a part of a broad movement called art pottery, or gallery vessels. Artists enlarged the size of a pot and created elaborate decorations in an attempt to attain sculptural status. When Takamori added teapots and ornamental fish, collectors soon grabbed up his work, attracting dealers in Los Angeles, New York and Seattle. While these works have undeniable charm, they are occasionally too cute for their own good, despite the often sexually graphic nudity.

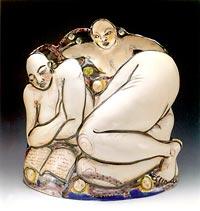

As viewers of both the show in Tacoma and Seattle's Henry Art Gallery will see, it wasn't until a 1996 residency at a ceramics workshop in the Netherlands that Takamori made his giant step forward. Reconnecting to his post-World War II Japanese roots, he began depicting peasants and city people in multiple-figure groups of slightly-less-than-life-size dimensions. With greater realistic detail, they are three-dimensional documents of postwar Japanese life. Tender without being sentimental, appealing without being cloying, the sculptures of the past decade demonstrate Takamori's late-won maturity.

In a further improvement, Takamori began combining vignettes of villagers with figures from famous European paintings. This happy cultural clash also broadened the scope of his vision. Visitors will have fun identifying the paintings from which Takamori lifted the familiar figures, such as duchesses and court dwarfs from Goya and Velázquez.

At the Henry show, curator Elizabeth Brown allowed Takamori to choose supplemental works from the museum's permanent collection. In one of two rooms he has selected Asian pottery. In the other there are images of children, which are also a central theme in Takamori's art. With or without parents, playing on their way to school, they are animated and convincing, light years from the generic surface decoration on the earlier pots. And the photographs and prints Takamori chose to accompany two of his four "laughing monks" are fitting.

Two tiny etchings by Marie Laurencin and James McNeill Whistler are joined by several 19th- and 20th-century Japanese color-woodblock scenes of children playing. Most of the photographs in the same room are socially concerned shots of slum children by Helen Levitt, Penny Gentieu, Marion Palfi and others. Parents will need to decide if this exhibit is appropriate for their children: Two color prints of nude babies and toddlers by Barbara Jo Revelle and Nan Goldin depict genitalia, and Edward Weston's 1925 photograph of his young son, Neil, shows a nude torso.

Across the hallway, things lighten up with Takamori's two other seated monks. This time, they are drinking. Displayed on the table between them, the pots brought out of storage offer an unusual opportunity to see brilliant examples of Chinese, Japanese and American ceramics. This is a must for all who make pottery or enjoy it.

A kind of fun crash course in names, shapes, glazes and purposes, "The Laughing Monks" explains why ceramics are Asia's most exalted art form. Using the helpful wall labels, visitors can both enjoy and learn. Takamori's powerful, lifelike figures and their imaginary drinking vessels will trigger conversations and explain all sorts of differences between high-fire and low-fire ceramics or why Chinese and Japanese potters wanted to emulate natural shapes like gourds and mangoes in their pots.

Luckily for us — and American art — Takamori left the old world for the new. Combining both in his best work, he has brought new insights into Japanese and American culture.

"Akio Takamori: The Laughing Monks," 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesdays-Sundays (11 a.m.-8 p.m. Thursdays), Saturday through Oct. 22, Henry Art Gallery,

University of Washington campus at 15th Avenue Northeast and Northeast 41st Street, Seattle; $6-$10, free for students and children 13 and younge

r (206-543-2280 or www.henryart.org). Takamori will discuss his work during a free lecture at 7 p.m. Thursday at the Henry.

"Between Clouds of Memory: The Ceramic Art of Akio Takamori," 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesdays-Saturdays (10 a.m.-8 p.m. Thursdays), noon-5 p.m. Sundays, through Oct. 8, Tacoma Art Museum, 1701 Pacific Ave., Tacoma; $6.50-$7.50, $25 for families, free for children 5 and younger (253-272-4258 or www.TacomaArtMuseum.org).