With Vision And Ambition

BARTLETT SHER IS standing in a ballroom at the Marriott Marquis Hotel, a stone's throw from Times Square. An opening-night party is under way, and well-wishers in fancy dress are buzzing around the lanky director.

Old friends, theater folk and media types are stepping up to congratulate Sher on his latest achievement: a sterling Broadway revival of the 1935 Clifford Odets play "Awake and Sing!," featuring such stars as Mark Ruffalo, Lauren Ambrose and Ben Gazzara.

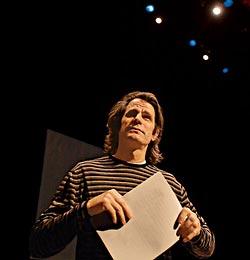

With his collar-length hair and gangly boyishness, Sher looks rather like a rocker suited up for a family wedding. But don't let appearances fool you.

Sher is both iconoclast and consummate insider as he shakes the hands, returns the hugs and accepts the tributes, a bemused grin softening his angular features.

A Broadway fete is only this upbeat if the show smells like a hit. And "Awake and Sing!" does — as the admiring reviews and eight Tony Award nominations will later verify.

But while he's savoring this moment, part of Sher's mind is drifting west — far west — to Seattle. And to an imminent rendezvous with the despotic royal in Shakespeare's "Richard III."

"I don't trust comfort too much," Sher reflects later. "No matter what's happening I'm always looking for the next thing, and for where the edge is."

That restless artistic and intellectual ambition, as well as the ability to function as both free spirit and inside-track player, have sent Sher shuttling from coast to coast — balancing the dazzling demands of Broadway with the quieter but no-less-intense needs of the cozy, nonprofit playhouse he runs in Seattle.

Back when he became the new artistic director of the Intiman Theatre in 2000, the common local reaction was: "Bart who?"

That was then. Sher was a brash, Brooklyn-based director of 40 with grand ideas, zero Seattle credits and no Broadway cachet.

Today, due to his well-honed talent and killer work ethic, Sher is on the short A-list of Broadway directors. His first outings there won him back-to-back Tony directing nominations, in 2005 for the musical "The Light in the Piazza," this year for "Awake and Sing!"

He's been chosen to stage "The Barber of Seville" for the Metropolitan Opera this fall, and a Broadway revival of "South Pacific" in 2008.

In Seattle, he built on the efforts of former Intiman artistic directors Warner Shook, Elizabeth Huddle and founder Margaret Booker to make the Seattle Center venue a prime arena for new plays, musicals and classics.

And in their "American Cycle," he and Intiman managing director Laura Penn have turned a multiyear roundup of standard literary works ("The Grapes of Wrath," "Our Town") into a city-wide, socio-cultural symposium.

It's a rare, dizzying kind of success for a director who shot into the national spotlight only recently, and whose after-glow won Intiman a coveted Tony Award this year for "best regional theater." But Sher is no overnight wonder.

Since the 1980s, he's worked tirelessly on off-Broadway stages and at regional theaters from Connecticut to Maine. With 20 of Shakespeare's 37 plays under his belt, he's joined an elite cadre of U.S. directors prized for mastering both classical and modern texts.

Broadway colleague Jack O'Brien, who directed such New York smashes as "Hairspray" and "Dirty Rotten Scoundrels," says, "Bart allows a play to bloom and the actors to shine, and creates this quiet elegance that never calls attention to itself."

Kurt Beattie, artistic head of Seattle's ACT Theatre, says his friendly cross-town rival has brought to the Seattle scene "an individual vision of what theater can and should be."

So what makes Sher run so hard and fast after that vision? Is he as good as the hype surrounding him? And perhaps most importantly for local audiences, does this brainy, charming "theater rat" have the stamina — and the desire — to keep up the cross-country commute?

SITTING IN THE AIRY, newly remodeled Queen Anne condo he shares with his actress wife Kristin Flanders and their 5-year-old daughter, Lucia, Sher speaks openly about where he's coming from, and where he's headed.

Just as he can look dashing one moment and nerdy the next, so can Sher sound alternately hyper-confident and self-deprecating when narrating his personal story.

Raised in San Francisco in an affluent Catholic clan of seven kids, Sher says that "being five down in birth order made me want to stand out. I always want to reach the farthest I can reach. And I'm always nervous. There's a lot of measuring myself against other people I think are better than me."

A rigorous Jesuit education at the elite St. Ignatius prep school (and later at Holy Cross College in Massachusetts) stoked Sher's fervent idealism and raw competitiveness, and "totally prepared me for the work I do today," he says.

Seeing acting legends Alec Guinness and John Gielgud in plays during a family trip to London was an early artistic inspiration.

Another: the hippie-trippy Grateful Dead concerts he went to in 1970s San Francisco. Still an ardent "Dead Head," Sher says the intense interaction between the rockers and their fans "had a huge impact on my perception of what culture could be."

Offstage, there was the drama of his parents' rancorous separation, when Sher was 14. And the subsequent revelation that Sher's immigrant father was Jewish by birth — a heritage he hid from his children.

"It was so weird finding that out when I was 15," says Sher, who today cherishes old photos of Jewish relatives in a Lithuanian shtetl (village). "But being part Jewish has always struck me as a very great thing. I found it satisfying, exciting, enriching and a little mysterious."

The dual identity of Jew and Catholic, social insider and outsider, was further forged at Holy Cross. The popular Sher was "always a bit rebellious and adventurous," joining anti-nuclear protests and writing an audacious campus play titled "Fish Every Day."

"I liked exploring boundaries and breaking rules," he comments wryly.

Jonathan Moscone recalls that trait fondly. While a student at St. Ignatius, he was in a school version of Agatha Christie's "Ten Little Indians" that Sher directed during a post-college teaching stint at his old prep school.

"Bart hated the design and really kicked some butt to make it more beautiful," says Moscone, who now runs the California Shakespeare Festival. "I was so enamored with how much excellence he demanded from us. The play was a silly little chestnut. But he made it a really scary, thrilling piece of theater."

Sher soon headed off in search of more theater experience. In San Diego he cofounded a new company, the San Diego Public Theatre. Says Anne Marie Welsh, drama critic for the San Diego Union Tribune, "Bart did a lot of terrific work here. I so appreciated his intellect and the quality of his imagination."

Welsh recalls one "wild" Sher show about leftist firebrand Emma Goldman, enacted by Sher's then-girlfriend and collaborator, Carla Kirkwood, which included a staged street rally at a local train station.

He later spent time in Europe, studying directing at England's University of Leeds and traveling around sampling the work of major avant-garde stage artists.

Sher was entranced by the semi-abstract, very personal visions of Tadeusz Kantor ("a half-Jewish, half-Catholic Polish guy whose work... opened all these possibilities for me"). He loved famed Italian director Giorgio Strehler's lyrical approach to Shakespeare, and the folkloric-political dramas of Nigerian Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka.

The next step: back in the U.S., assisting "risky" American directors — Robert Woodruff, Mark Lamos, Peter Sellars — doing bold work in regional theaters.

But the mentor Sher refers to most often is the late Garland Wright, whom he worked with for five years as a resident director at the Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis.

"Garland taught me how to direct on a thrust stage, which we also have at the Intiman, with audience on three sides looking at the work from three different perspectives," Sher explains. "Watching him create a stage picture was like learning how to fly an airplane."

Wright also passed on his belief in theater as a civic act. "Garland felt that as an artist you have a larger responsibility, not just to yourself but to the values expressed in your work, to your community, to how you live in the world."

Sher had a chance to connect with a new community, and refine his Shakespeare chops, at the Idaho Shakespeare Festival. Charlie Fee (artistic head of both the Boise theater and Cleveland's Great Lakes Shakespeare Festival) often hired Sher to direct, and encouraged him not to "dumb down" his work for Idaho audiences.

"Clarity was important, because it doesn't make any difference what we do on stage if the audience doesn't get it," says Fee. "But when Bart did a 'Cymbeline' with singing Marlboro cowboys and Peking Opera bits, the audience got it. And they loved it."

In 1999, Sher "auditioned" for the Intiman job in Boise. He was living with future wife Flanders in Brooklyn, freelance directing and hating "the constant traveling, exhaustion, the feeling of not being connected to anywhere."

When Sher became a finalist for the Seattle post, Penn and several Intiman trustees flew to Boise to see his work for the first time.

He got the gig.

Why? "When theater is great there's a kind of endorphin phenomenon, a release of energy in the psyche," Penn says of Sher's searing Idaho production of Shakespeare's "Titus Andronicus." " 'Titus' was that kind of high. It felt so immediate, as if this Elizabethan play was written a week ago."

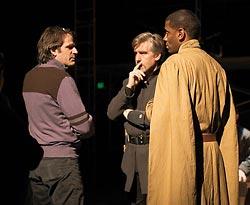

SEVEN BUSY YEARS later, on a May morning in a drab rehearsal hall, Sher is directing local and imported actors in "Richard III."

He has staged the famed history play twice before elsewhere, following a habit of revisiting some classics "because they're so rich, so deep; you just never get to the end of them."

But Sher isn't merely repeating himself. Known for his keen attention to textual detail, he's rethinking every line, pause and gesture in a scene where King Richard intrudes on a meeting of court rivals and allies.

There's laughter and joking in the room, but also the bristling force-field of a demanding director with sky-high expectations.

"Bart can be very tough on actors," says Fee. "But it's usually about trying to do very big plays very well, when your theater can only afford a few weeks of rehearsal."

"I want real collaborators," Sher explains. "If that's terrifying to some people, fine."

Flanders, a frequent Intiman actor, takes her mate's blunt directing manner in stride — and blasts him right back. "He'll futz around with me and have me jump through hoops. But it's all in service of the show."

Sher's confrontational style has alienated some good actors. But others find it stimulating, and happily work with him again and again.

"He's so damned smart, and I appreciate a smart director," says noted Seattle performer John Procaccino.

"Bart can be sarcastic, and if you don't know how to take it, it can be hurtful. He'll work you and work you and work you to get to his vision. But his vision is usually the right interpretation of the play."

Sher has expressed his vision most eloquently here in probing, beautifully composed renditions of works by Shakespeare, Ibsen, Goldoni, Chekhov. Other highlights: the debuts of "Nickel and Dimed" (an imperfect but stimulating adaptation of Barbara Ehrenreich's book about low-wage workers), "The Singing Forest" (an engrossing family saga by Craig Lucas), and the Broadway hit "Light in the Piazza."

"Good theater can mean different things," Sher muses. "Sometimes it's asking hard questions about our lives. Sometimes it's just about beauty. It should be deeply entertaining, but not an opiate. It should be a way of engaging with the culture, not disengaging or escaping it."

Sher's Intiman stand isn't beyond criticism. Some view his imagistic use of scenic effects as "gimmicky." And the track record for shows he's assigned to other directors is a lot spottier than his own productions. He readily admits missteps. "I trust the intelligence of our audience. If something doesn't hit and land, they tell me. It's a real relationship, and I feel lucky to serve them."

But the broad consensus is that Intiman is lucky to have Sher. Which again raises the question: for how long?

Sher can't say exactly. But he insists, "I like being part of a city, a community, a neighborhood. And what I do in Seattle makes what I do in New York possible."

He extended his Intiman contract to March of 2008. And he'll gladly voice a future wish list, which includes projects with Guettel, Lucas and "Angels in America" author Tony Kushner, more Chekhov, and some "big" Shakespeares he's never directed ( "Hamlet," "King Lear").

But more and more New York gigs are vying for Sher's time and attention. He was set to direct a second Intiman show this year but bowed out to stage the national tour of "Light in the Piazza," which will come to Seattle.

And he is frankly weary of the fiscal constraints at Intiman. Ticket sales are growing, but the theater has a modest annual budget of $5 million, and carries a $1 million debt.

A new funding drive to retire the debt and invest in more artistic perks (longer rehearsals, new projects, larger casts) may get a boost from the regional Tony prize. Still, commuting on the red-eye can get old — even for someone as loyal and energetic as Sher.

"There's a lot to be said for a director having a regional home base," says Lincoln Center Theater head Andre Bishop, producer of "Piazza" and "Awake and Sing!" on Broadway. "But it's too early to tell with Bart. His talent must feed the Intiman, but Intiman must feed him creatively, too. The institution and the person have to give to make it work." Daniel Sullivan made it work, running the Seattle Repertory Theatre for 17 years while crafting hits on Broadway. So did O'Brien, who has headed San Diego's Old Globe Theatre for 20-plus years.

For his part, Sher insists, "I'm not in a situation where I'm saying, 'Give me this or I'm going.' I love Seattle. I still want to try things out here, to speak to this audience. I love this audience.

"Yes, it would be great if people can understand what (we need) to make this place really special."

Sher pauses, then takes the plunge, "But really, I'd like to stay here my whole creative life."

You want to believe him.

Misha Berson is The Seattle Times theater critic. Benjamin Benschneider is a Pacific Northwest magazine staff photographer.