EMTs are listening to patients' dying wishes

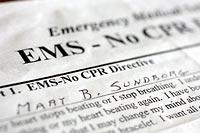

Mary Sundborg was a spirited woman of 100 ½ who had long endured advanced colon cancer and two strokes. And she knew how she wanted to die: at home, peacefully, with dignity.

So with the help of her eldest son, she signed an official order specifically directing emergency responders not to attempt CPR.

Then came Jan. 3, the day Sundborg stopped breathing. Her nurse, who wasn't sure at first what was happening, called 911. When emergency medical technicians (EMTs) from the Fire Department arrived at her Magnolia home, they pulled her out of bed, attached their equipment and began pushing on her chest.

"Put her back in bed!" the nurse yelled. Sundborg didn't want to be resuscitated, she told them, waving the "No-CPR" order. One of the emergency workers told her the order had expired, and kept going.

But Sundborg was dead.

"It was terrible, absolutely terrible," said her nurse, Bonnie England. "It felt very disrespectful. It was just so wrong."

And it was far from an isolated case. Emergency medical responders, long trained that a 911 call is a request for resuscitation, have routinely ignored family members who ask that CPR not be given to their loved ones who are dying of terminal illnesses.

This year, that is changing in most King County jurisdictions, thanks largely to years of effort by two South King County paramedics who saw the current system as an affront to patients' wishes for peaceful death.

For the first time, EMTs — the first responders to 911 calls — are being given the latitude to forgo resuscitation when they judge it to be "futile, inappropriate and inhumane" — even when there is no official paperwork.

The protocol, dubbed "Compelling Reasons," is the first of its kind in the country. A study of a pilot program in South King County fire districts, published in the latest edition of Annals of Internal Medicine, found that all but a few EMTs felt comfortable letting their patients die in peace.

"Sometimes, the right thing to do is to not do a resuscitation," said Dr. Mickey Eisenberg, medical director of King County Emergency Medical Services. "The reality is you have to accept the concepts of patient autonomy and futility."

Not everyone is accepting the changes wholeheartedly.

Bellevue Fire Department is still studying the protocol. And while the Seattle Fire Department, the agency that gave CPR to Sundborg, has officially signed on to the new training, "our mind-set is to save a life," said spokeswoman Lt. Sue Stangl.

"Now, all of a sudden, we're asked to question that judgment."

"It was wrong"

When someone calls 911, a swift-moving system clicks into place as EMTs are dispatched.

Until now, protocols have left EMTs with little discretion. They weren't allowed to accept family members' word that a patient had a fatal disease and didn't want CPR. Even properly signed "Do Not Resuscitate" (DNR) orders were usually ignored when EMTs first arrived.

"We wouldn't even talk to the family member," said Tom Curtis, a Renton EMT. "We'd rush in, rush right past them, throw down our equipment and get to work. We're really good at pushing people out of the way and just taking over."

That response is "deeply embedded in the system," Eisenberg says. "You don't want people to get to the scene and start deliberating, because seconds make a difference."

Once under way, a resuscitation effort could be halted by paramedics, more highly trained emergency workers who are summoned on more serious calls, but only after consulting with doctors. And by then, some families complained bitterly, their loved one's wishes had been violated.

It was one of those cases, in the early 1990s, that left King County Medic One paramedic Sylvia Feder determined to change the system.

The EMTs who had rushed to the South King County home found a frail old man, motionless in his bed. The EMTs expertly executed their choreography, pulling him to the floor, snapping a mask onto his face and pushing on his chest.

The man's wife was sobbing and asking them to stop. One EMT held her back as the others did as they were trained — and required — to do.

The EMTs had done everything right. But when she arrived minutes later, Feder realized with a wave of shame that what had happened was just wrong. The man was dying of incurable liver cancer.

"For the patient, it was wrong because there was no chance of a good outcome," Feder said. "For the wife, it was wrong because this wasn't the way she wanted it to end. For the EMTs, it was wrong because they didn't want to use their lifesaving skills in that situation, but they had no choice."

So in 1997, she and fellow Medic One paramedic Roger Matheny decided to confront the issue.

But when they aired their proposal at a meeting of emergency medical services leaders, there were lots of questions.

What if a young wife was trying to get rid of a rich old husband? Or maybe the "spouse" wasn't really a spouse but a burglar — even a killer? Was it fair to put a life-or-death decision in the hands of an EMT? Could someone be sued if they made the wrong call?

Many felt it was safest just to do CPR. After all, while King County's action-oriented system has helped push it to the top of the nation in cardiac-arrest survival rates, the truth is, most out-of-hospital resuscitation attempts fail. So since the patient will never know, someone said, what's the harm in trying?

But one doctor countered that there was plenty of harm: Someone could be revived only to endure more suffering. Families could be traumatized. And medical teams would be wasting time, and money, attempting to revive people who didn't want it.

A lawyer advised the leaders that emergency responders who act in good faith are generally protected by the law.

The medical director for King County's emergency medical services at the time was initially skeptical. But he endorsed it, citing "changes in society's views about death."

South King County fire districts adopted the protocol in 1998. But other jurisdictions, including Seattle and Bellevue, declined.

No more autopilot

Now, under Compelling Reasons, EMTs will be allowed to withhold resuscitation provided the patient is in the final stages of a terminal condition and family members request — in writing or verbally — that CPR not be performed.

The study on South King County's experiences since 1998 found that more than 90 percent of EMTs reported that the decision to withhold CPR from terminally ill patients was not difficult.

What's stressful for emergency responders, Matheny says, is "being forced to do an inhumane thing to people despite their wishes."

The protocol, says Eisenberg, allows EMTs to use professional judgment and not just operate on autopilot.

An editorial published with the study called the new protocol a "welcome alternative" to the always-resuscitate imperative.

"I think patients have rights, even though they're dead," says Ed Plumlee, deputy chief at South King Fire & Rescue.

Nonetheless, some jurisdictions aren't embracing the new policy, and Eisenberg has no power to force them to do so. In fact, wary EMTs can invoke a clause in the protocol that advises them to default to resuscitation when in doubt.

For now, Bellevue's Fire Department doesn't train EMTs in the policy, but is "continuing to review" it, says Michael Remington, commander of the EMS division.

In Seattle, Jesse Youngs, SFD's chief of training, says training around death and dying is in a "state of change right now." While Seattle is teaching EMTs the policy, says Lt. Jonathan Larsen, SFD's emergency medical services training coordinator, it takes time for any change to be accepted.

"If Compelling Reasons are present, then that allows us to do the ethical thing," Larsen says. Still, "the default position is going to be to act."

That may have been what happened to Mary Sundborg.

England, her nurse, said she would never have called 911 if she'd thought Sundborg would be subjected to CPR. And her doctor, David Tauben of Seattle, said there was "explicit documentation that was to protect her" from such efforts.

The whole episode has left Sundborg's 93-year-old widower, George Sundborg, shaken. He worries he won't be able to protect himself from unwanted resuscitation attempts when his time comes.

"I thought I had dotted every 'i' and crossed every 't,' " laments Pierre Sundborg, the couple's eldest son. "We all thought we'd done everything perfectly to spare Mom any pain."

Now, Eisenberg says patient wishes must rule. "We want EMTs to acknowledge that people call 911 for a multitude of reasons, not simply for resuscitation," he said.

"With education, people will realize it's the right thing to do."

Carol M. Ostrom: 206-464-2249 or costrom@seattletimes.com

The new "Compelling Reasons" protocol allows emergency medical technicians in King County to withhold resuscitation if a patient is terminally ill and family members or caregivers present a written order or verbally refuse resuscitation. The program, still being evaluated by some jurisdictions, is designed to help responders determine whether resuscitation would be "futile, inappropriate and inhumane."

Sign a Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) form:

This new form, giving patients many choices including "Do Not Resuscitate," takes the place of an earlier "EMS/No CPR" form, which is still valid if signed. Doctors can get the forms from the Washington State Medical Association, 800-237-3329. To see a sample form, look at www.wsma.org/patients/polst.html. Patients can get a form from Compassion & Choices, 206-256-1636 or 877-222-2816.Know what to expect: If a terminally ill patient plans to die at home, talk to his or her physician or hospice caregiver about how to prepare, and make sure all family members and caregivers are included in plans and know what to do afterward.

Decide whether to call 911: Ideally, a family that is prepared for death will not need to call 911. But sometimes families are overwhelmed or need help. If 911 is called, make sure wishes are clear to the emergency personnel as soon as they arrive.

Withholding resuscitation The study![]()

![]()

• After the protocol was adopted in South King County, CPR was withheld more than twice as often in cardiac-arrest cases.

• In the majority of those cases, emergency workers were honoring verbal requests.

• In private homes, only about a third of families offered written directives.

• In all cases in which CPR was withheld, patients had terminal conditions (35 percent had terminal cancer, 63 percent had another terminal condition such as renal failure, and one patient had an unknown terminal condition with hospice in attendance).

• More than 90 percent of the EMTs said they were comfortable making the decision, and none found it difficult.

Source: Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 144, No. 9, 2 May 2006