An activist-turned-informant

EUGENE, Ore. — The arsonists hit before dawn, laying down fuel-soaked sheets and jugs of gasoline to torch 35 SUVs at a Chevrolet dealership.

The communiqué from the saboteurs — acting under the banner of the Earth Liberation Front — proclaimed a new, more militant era, when the sins of the "rich who parade around in their armored existence" would no longer go unchallenged.

Federal, state and local officials converged on the scene after the March 2001 attack, sifting through charred wreckage for evidence — just as they had in more than a dozen other major arson attacks around the West claimed by the ELF or the Animal Liberation Front.

The investigation hit a dead end. As in the other attacks, prosecutors couldn't muster enough evidence to charge anyone.

"If you don't get a break, arson is a really tough case to make," said Thad Buchanan, a retired Eugene police captain involved in the investigations. "Most of your evidence burns up."

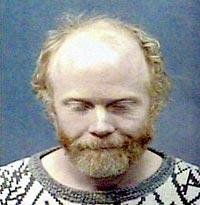

Three years after the Eugene fires, investigators finally got their break: A sinewy, tattooed heavy-metal guitarist named Jake Ferguson agreed to cooperate and donned recording wires to meet with other activists.

Soon, the secrets of the underground network thought responsible for the attacks began to be exposed.

Ferguson was a high-profile participant in some of these crimes, according to court documents and court statements by defense attorneys with access to unreleased documents.

It is unclear whether he had any role in the Eugene fires. But he admits to helping out in at least four arsons, including a 1998 fire at a federal facility in Olympia, according to a court statement by Craig Weinerman, a federal public defender involved in the case.

As federal prosecutors prepare for trial this fall, Ferguson's tapes and testimony will likely play a large role in the fate of 13 men and women accused of a conspiracy to carry out 17 acts of arson and sabotage between 1996 and 2001.

Most of those accused now face spending decades in prison if convicted. Some could wind up with life sentences if found guilty at trial.

So far, Ferguson remains free and hasn't been charged with any crimes.

But his cooperation with investigators has made him a notorious figure among militant environmentalists: Ferguson has received threatening phone calls and been repeatedly trashed on activist Web sites as a turncoat, snitch and worse.

In an interview with The Seattle Times, Ferguson declined to comment on the alleged crimes and bristled at accusations that he was the first to fold.

"I didn't roll; people rolled on me, and I was faced with a situation where I could go to jail for the rest of my life," Ferguson said.

A devoted father who liked guitar, Aikido Ferguson lived in the Whiteaker neighborhood of Eugene, a collection of aging wooden homes. It's a place where people can find shelter in aging buses parked in a front yard or a yurt that features access to an organic garden and wood-fired sauna, and — in years past — weekly meetings to debate anarchist philosophy.

He was known for being into his music, playing lead guitar in a band at a local bar. He also trained in Aikido, and, friends say, was devoted to his young son, who lives with his mother.

There was another side to Ferguson, as well.

In 1999, he was arrested on charges of carrying a concealed weapon in his pickup — a 9 mm handgun, according to Eugene court records.

He also has struggled with a heroin addiction, and at times displayed a volatile temper, according to Micah Griffin, a former bandmate.

"There was a certain aura about him," said a former housemate. "He was the bad boy. And there was a certain attraction to that in an anarchist movement full of pirate talk."

Ferguson earned some of his early activist credentials when he joined the marathon Warner Creek logging protests of 1995 and 1996.

Protesters spent more than 300 days blockading a road that led to a 14-acre patchwork of old-growth timber scheduled to be cut in a burned-over area of the Willamette National Forest.

At Warner Creek, Ferguson was a tactician, someone who helped fortify the lines by digging ditches and building barricades.

In a documentary titled "Pickaxe," a bearded Ferguson smiles as his head pokes above the walls of a log stockade strung across the road.

"We've had schoolkids from Vermont come here to do all-night watch shifts with their teachers," Ferguson told the interviewer. "It's really been an inspirational place for activists from all over the country."

The protest spurred nonviolent civil disobedience around the region, with hundreds arrested before the Clinton administration finally backed off from logging that tract.

There was tension about how far to take the protests: Some people held fast to civil disobedience in the traditions of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Gandhi.

Others thought violence could be justified against an industrial society doing plenty of violence against the Earth.

"It was a constant debate, and people weren't just sitting in a room, they were sitting in the middle of the road, so the argument was based on the reality of what might be happening that day," said Tim Lewis, an activist who produced the "Pickaxe" documentary.

Those camped out included Kevin Tubbs, a Nebraska-reared son of a Vietnam Marine veteran. Then 26, Tubbs already had made a name for himself as an animal-rights activist with a passion for rescuing stray animals.

At Warner Creek, Tubbs tied himself on top of a wooden tripod set in the middle of a road. It was rigged so that the smallest bump from a logging truck would dislodge the structure, and "bring me crashing to my death," he told an interviewer in the documentary.

The protest also drew Bill Rodgers, a soft-spoken, balding man who loved to hike, explore caves and read books. He had a mystical streak, taking the nickname "Avalon," from "The Mists of Avalon," a novel about King Arthur told from the perspective of a druid priestess.

Others who joined the Warner Creek protest don't recall any special bonding among Tubbs, Rodgers and Ferguson.

But court documents and statements by attorneys allege that in the years to come, the trio — sometimes working side by side — would help carry out a wave of arson attacks on behalf of the Earth Liberation Front and Animal Liberation Front.

The first ELF attack took place a month after the Warner Creek protests, a failed attempt to burn down a Willamette National Forest ranger building. Two nights later another ranger station burned down.

In the years that followed, the saboteurs hit 15 other targets with a mix of stealth and bravado, sometimes spray-painting the ELF or ALF initials at the scene. They used homemade bombs, sometimes consisting of 5-gallon jugs filled with gasoline and detonated with electronic timers. But they left scant evidence behind.

To make headway, investigators needed somehow — some way — to penetrate the underground.

"It was very difficult. It was a very tight group. We knew that it was going to be a long, slow process," said Buchanan, the retired Eugene police captain.

Unexpected lead gives investigators "a red flag"

Around the time of the Chevrolet dealership fire, police and federal investigators got an unexpected lead.

Shortly after the arson, a woman reported a stolen vehicle and believed that Ferguson had taken it, according to Buchanan. She then had a change of heart and withdrew that report.

A few days later, another woman showed up at the Eugene police station and asked for information about the stolen-vehicle report and the fire at the dealership, according to police and federal sources.

Police were surprised by this query.

Could Ferguson — and this truck — have been involved with the fires?

"It was a tremendous red flag," Buchanan said. "Before that, we had never head of Ferguson. He wasn't on our radar."

Investigators located the truck. But a search didn't turn up evidence that linked the fires to Ferguson, according to Buchanan.

But Ferguson was still a suspect when federal investigators began looking into the dealership fire again. By then, ELF and ALF attacks in the Pacific Northwest had ebbed, but other actions were continuing elsewhere.

In Eugene, a federal grand jury summoned numerous witnesses, including several of Ferguson's friends.

By the summer of 2004, Ferguson would tell friends that "the feds" were closing in on him, even following him as he drove through town.

"Most of the time he joked about everything, and it was hard to know when to take him seriously," said a former housemate. "But the one time he really seemed serious, he said that they [federal authorities] were trying to get him for [the dealership] fire."

Several defense attorneys say they've seen no evidence that Ferguson participated in the dealership fires.

Federal prosecutors decline to discuss Ferguson, though U.S. Attorney Karin Immergut said in a news conference that inside information was of "critical importance" in cracking the case.

Ferguson did not say who put the federal officials on his tail, what information persuaded him to cooperate or what kind of deal, if any, he struck with prosecutors.

But by September 2004, Ferguson was cooperating with investigators, according to defense attorneys who have gained access to numerous FBI affidavits.

In some of those documents filed in court, Ferguson appears as "CW-1" (Confidential Witness 1) or simply "CW" (Confidential Witness), according to Weinerman, a defense attorney for an alleged co-conspirator in some of the arsons. In indictment papers that outline the crimes, Ferguson appears as a "person known to the Grand Jury," according to a motion filed by another defense attorney.

In these documents, Ferguson, as CW, talks about joining Tubbs on a 1998 road trip from Eugene to Olympia. There, they joined with Rodgers in an arson attack on a federal wildlife-research facility. The group had an unreliable vehicle, a van that kept breaking down. Eventually, it had to be dropped off at a Federal Way repair shop, according to an FBI affidavit.

In late 2000, Ferguson claimed to have joined Tubbs and three other people to scout out another target — an Oregon poplar farm, which would eventually be set fire to on May 21, 2001, along with the UW Urban Horticulture Center. And as an informant, he would later return to the area to point out landmarks to an FBI agent.

To bolster the case against other alleged cell members, Ferguson also agreed to don a body recorder, and travel around the country coaxing at least six of his alleged accomplices to talk about past exploits. Those recordings included conversations with Tubbs reminiscing about the Olympia attack, and Rodgers discussing his work on a how-to manual, "Setting Fires with Electronic Timers."

Ferguson's work made him a notable recruit in a broader FBI effort to penetrate the ALF and ELF.

The feds begin to make arrests

The federal crackdown began early last December.

Rodgers was among the first taken into custody. He was arrested at the bookstore and community center that he had opened in Prescott, Ariz.

"Never did I imagine that things would turn out like this. I have been betrayed before and each time I was astonished, and saddened," Rodgers wrote from jail. "But this is the ultimate betrayal, delivered straight into the hands of my enemies. On top of all that, I can see that multiple parties are willing to blatantly lie and exaggerate."

He also wrote a will. Two weeks after his arrest, the 40-year-old Rodgers pulled a plastic bag over his head and committed suicide. His girlfriend received some 30 pages of letters, including a farewell note.

"Certain human cultures have been waging war against the Earth for millennia," Rodgers wrote. "I chose to fight on the side of bears, mountain lions, skunks, bats, saguaros, cliff rose and all things wild. I am just the most recent casualty in that war. But tonight I have made a jail break — I am returning home, to the Earth, to the place of my origins."

Tubbs, who was arrested in Eugene where he worked at an adult bookstore, made a different choice.

Accused of involvement in at least nine attacks, he faces the possibility of spending the rest of his life in prison. He has chosen to cooperate.

In a Jan. 31 letter, he appeared hopeful his assistance would earn him release on bail so he could reclaim his job as an assistant retail manager at an adult video and magazine store and share some time with his family and six cats and two dogs.

"I sincerely regret any involvement in the activities I am accused of," Tubbs wrote U.S. District Court Judge Thomas Coffin. "I was motivated only out of a desire for positive social change, but I have long since realized events like those actually do more harm than good. To prove this point, I am doing everything I can to help resolve this complicated case as quickly and easily as possible."

In a February court hearing, prosecutors portrayed Tubbs as a desperate man willing to die for the cause and a flight risk. They persuaded Coffin to deny the bail motion.

Ferguson has become a target for scorn

Ferguson, at least through early March, was still living in the Eugene area. Though he's kept a low profile, he became a target of scorn in some activist circles.

"The reason why a community has been shaken to the core is this: Jacob Ferguson," declared a posting on the Indymedia Portland Web site.

"In a community where there is distrust, even disgust for the federal government and especially its law-enforcement operatives, Jake pretended he was one of us. He was and is one of them."

A former housemate was surprised to see him earlier this year driving one of the ELF's despised symbols of industrial excess — a gray SUV. Ferguson said it was a rental vehicle.

Once this winter, Ferguson also ventured to an old Eugene hangout, the Tiny Tavern.

"I didn't know whether I wanted to hit him, or give him a hug," said Griffin, his former bandmate.

Ferguson told Griffin about his difficult upbringing without his father, who spent time in prison. Ferguson hoped his cooperation with the Justice Department would spare his own son the same fate.

Still, he feared he might have to serve as much as 10 years behind bars. Throughout their meeting, Ferguson was full of tears, sorrow and regret.

"He said he had become a victim of his own crimes," Griffin said.

Seattle Times researcher David Turim contributed to this report.

Hal Bernton: 206-464-2581 or hbernton@seattletimes.com

Is it terrorism?

FBI says yes, even though environmental militants target property, not people.

Related material

- FBI chronological summary of terrorist incidents, 1980-2004

- FBI report on intelligence sharing (PDF). The report discusses "social" protests, protesters and groups in several places, most notably on report page 34.