Lynnwood Redux

SEATTLE'S OFFICIAL northern city limit is at Northeast 145th Street, but everyone knows the metropolitan area sprawls far beyond that, through Shoreline, Edmonds, Lynnwood and on. And on. And still on.

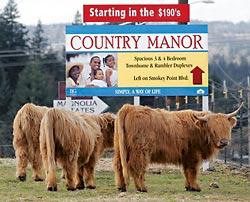

Which explains the remarkable transformation overtaking the ultimate in anonymous freeway exits, Smokey Point (also known as Exit 206) some 31 miles north of Seattle's political boundary. Big-box stores are about to erupt like toadstools. Like it or not, this is the new commercial frontier of Pugetopolis, Seattle's exploding edge.

"What happened is, nothing happened, for a long, long time," recalls Gloria Hirashima, city planner for Marysville, which has annexed commercial land on the west side of the Smokey Point interchange.

Then the Tulalip Tribes opened its mammoth casino and hosted retail development that includes a new outlet mall. The Interstate 5 corridor between the Snohomish and Stillaguamish rivers became an urban growth area under the state's Growth Management Act. Navy housing developments plopped onto forest and dairy land. And suddenly, exits to nowhere had become somewhere.

The result was offramp backups, congested arterials and commuter frustration.

One response was a recent remarkable campaign by some citizen activists to get the Smokey Point overpass widened to subdue the snarls of traffic. When the state said it had no money to keep up with growth, they went out and found some.

Another was the parallel explosion of development plans that has residents who thought they'd moved to a semi-rural, quiet enclave crying in dismay. "The growth comes up the highway like a plague, filling the pockets of developers and of those who choose to sell and run off, not caring about the destruction they leave behind," complains Laura Goldberg of Arlington. "I want to see Arlington remain a small, pedestrian family town surrounded by rural grace."

Arlington wants that, too, says Mayor Margaret Larson, 68, who grew up on nearby Lake Goodwin. But the town has hedged its bets by annexing Smokey Point, and turned a village into a city. "I just love the people coming," she said optimistically. But later, she added, "You wonder how Lynnwood got the way it is."

"Roads draw development and development draws roads," notes Doug MacDonald, secretary of Washington's Department of Transportation. And sure enough, Lowe's and Safeway have already planted themselves. On the heels of this latest interchange improvement will be a big-box "mall" to the west with Costco, Target and lesser stores, and a Wal-Mart Superstore to the east. Theaters, restaurants, light industry and housing tracts are expected to follow.

There is no "point" at Smokey Point. The crossroads got its name from a 1950s outdoor-barbecue restaurant started by Eric and Pearl Shurstad, who called their place the Smokey Point Café after the plume of smoke it generated. A Rite-Aid stands on the site today, just east of the freeway exit.

There was no town, no independent school district, no excitement. The area between Marysville and Arlington was a boggy swale of dairy farms interrupted by Arlington Airport, a World War II Navy field that has become the region's headquarters for private aviation. Its 500 airplanes include a fleet of 60 ultralights and the Flying Heritage Museum of vintage warbirds owned by Paul Allen.

But Marysville began extending utilities northward years ago in anticipation of becoming the next Lynnwood. That city has made 23 annexations just since 2000. Now Marysville joins Arlington at the freeway — and the two tiny river and farm towns occupy an urban growth boundary totaling 21 square miles, one quarter the size of Seattle.

Marysville's population of about 31,000 (58,000 in the urban growth area it is expected to complete annexing) and Arlington's 16,000 are both expected to double in 10 to 20 years, while the Tulalip Tribes is already planning a 380-room hotel, more entertainment centers, and more light manufacturing. The result should be a freeway corridor with a population roughly equivalent to today's Everett by 2025.

Freeway traffic past Smokey Point has risen 13 percent in just five years. Freeway collisions rose 50 percent in the same period — 171 cars hit the corridor's cable barrier on its median grass strip;13 crossed onto oncoming lanes, often after prying up the cable from underneath.

As a result, the seven miles of I-5 between Marysville and Smokey Point got the ultimate confirmation as an urban corridor in 2005: The speed limit was lowered from 70 miles an hour to 60, a dampening that now extends from Smokey Point to Tumwater, or more than 100 miles.

"Interstate 5 is steadily transiting from a rural interstate to an urban interstate," says Steve Gorcester, director of the state's Transportation Improvement Board. "That means more access points, lower speeds and more traffic."

Welcome to tomorrow.

FOR A LONG TIME, civilization seemed to be about packing more people into denser cities. Ancient Rome squeezed a million people into six square miles, a density roughly 25 times that of today's Seattle proper.

Even Seattle, in the days Green Lake was a camping destination, was laid out in a trim grid pattern to pack homes within reach of streetcar lines. Frederick Olmsted laid out a sweeping vision of parks the city retains today. Then came the automobile.

"The real growth crisis in Western Washington is because of the way development is stretched along the I-5 corridor," the transportation department's MacDonald notes.

In some ways, the Marysville-Smokey Point-Arlington explosion is an example of good planning, because it confines growth to a designated area along a freeway that provides a spine of transportation. Utilities and housing will be concentrated as infill occurs. The Seven Lakes area to the west, and the Cascade foothills to the east, will escape the brunt of more people coming in the next two decades.

Yet this is growth of the car, by the car and for the car. Commuters file down to Boeing in Everett from as far as Darrington and Mount Vernon. While Arlington has a high concentration of jobs around its airport, Marysville is primarily a bedroom community. It empties by day, refills by night.

Even retail has changed to accommodate the auto. Bill Binford, a Smokey Point real-estate investor who co-chaired the group that expanded the interchange, says enclosed malls have been eclipsed by separate, big-box stores with their own parking lots.

"Everyone is pressed for time," Binford explains. "Running into an enclosed mall takes more time." So the "mall" under construction in the Lakewood neighborhood west of Smokey Point is pedestrian in design only in that it will have more sidewalks and landscaping than the usual big-box sprawl. It still is designed to get the car as close to the front door as possible.

Because Marysville and Arlington annexed a hodgepodge inheritance of old Snohomish County zoning, the new cities are an odd quilt. Both old towns have a small downtown core dating from pioneer days and a residential nucleus laid out in old suburban style: grid streets, quarter-acre lots, and trim but modest homes.

Both cities have plans to revitalize their downtowns using tax money gleaned from the new super-stores — even though those same super-stores, of course, threaten to make those downtowns obsolete. The new overlords of 20 square miles are still focused on a few downtown blocks — while Wal-Mart will have three super-stores within six miles of each other: one each in Tulalip, Marysville and Smokey Point.

And both cities are a helter-skelter pattern of light industry, housing and farm. They are focused not on a harbor, or key intersection, but rather the airport, the rail lines and especially the freeway. The unifying elements are the north-south highways: Interstate 5, Highway 99 to its east, and Highway 9 to the east of that. The notion of a city "center" has been replaced with retail nodes on a spinal cord of pavement.

If life is influenced by environment, this implies a lifestyle of far-flung neighborhoods, not corner groceries. It is represented by soccer moms connecting disconnected kids by car, and dads trading a longer commute for a lower mortgage. You can still get a new three- to four-bedroom home for under $300,000 near Smokey Point, and Arlington has just built or remodeled five schools. Marysville in particular is home to young, middle-income families. It has put in 47 parks in 15 years, 44 of them developer-built small playgrounds.

No one pretends this looks pretty. "It's hard to make Costco look different," Hirashima allows. "They have a message to send, value, so that's how they do their design."

But it is 21st century America, an America in some ways deliberately uglier and more inconvenient than that of a hundred years ago. In a region unable to build a monorail or agree on a viaduct fix, the ability to plan comprehensively for the 50,000 to 100,000 newcomers coming each year tends to stutter.

Marysville does have an ambitious plan to re-establish a huge Snohomish River wetland at the city's southeastern end and use it as the base of a trail system. Hirashima would also like to see the city's downtown turn its face to the river and redevelop an old marina. Thomas Klugman, manager of the Marysville Town Center shopping center, responds that reorienting the tiny mall from road to river is impractical.

"But," he ventures, "we're all for them improving Fourth Street."

It's all about the car.

WHEN SMOKEY POINT business people realized in 2003 that their interchange had fallen off the state list of transportation improvements, they didn't panic. They mobilized, creating TRAP, or Transportation Relief Action Plan.

"We felt trapped up here," explained Gigi Burke, co-chair and a director of Crown Distributing, a beer trucking company that moved north from Everett to get more room and found itself locked in an interchange traffic jam. "We recognized instantly we had a problem." The family-owned company had bought 110 acres for itself and future development in partnership with a farmer, but literally couldn't drive away with any efficiency. Overall, TRAP estimated 2,500 would-be jobs in Arlington were waiting for less congestion.

Politicians from Arlington Mayor Bob Kraski to those in Congress jumped in. Rep. Rick Larsen found $2 million in the House. Sen. Patty Murray found another $1 million in the Senate. The state put in $3 million from a separate fund, and local government chipped in. Eventually the partnership had $9.2 million — about one third of what was required to redo the entire master plan — and work started on the hardest part, widening the overpass from two to six lanes.

That's just the beginning. Plans are afoot for new cloverleaf ramps to avoid clogging left-turn lanes, a park-and-ride lot, and widening of the 172nd Street arterial that the interchange feeds several miles east to Highway 9. Eventually the total for traffic will reach tens of millions of dollars.

Such public spending can mean private gain. After the Crown property increased in value $2 million over five years, it jumped another $2 million — roughly a 20 percent increase — as soon as the wider overpass was completed.

The stakes are high for government, too. Improvements increase the chances for a Wal-Mart, which is paying development fees of $750,000 to Arlington, $326,000 to the state, and $1.13 million to Snohomish County for the traffic, drainage and other improvements its massive footprint will require. Even though the Johnny's food store was put out of business by Food Pavilion, and Food Pavilion closed because of the threat of Safeway and Wal-Mart, fresh stores can seduce most city councils.

Cities constantly bet they make more off retail growth, in initial fees and subsequent taxes, than the stores will eat up in the need for roads, police, fire, schools and other costs as people settle around them. Yet taxes are consistently higher in urban than rural areas.

There's no choice, Smokey Point business leaders argue.

"We continue to have children," says Becky Foster, another TRAP leader who owns a flooring business in a one-time barn and factory. She welcomes jobs, population and increased choices in shopping, dining and entertainment. "We can have the best of both worlds," growth and environment, at the edge of Pugetopolis, she argues.

"There's nothing worse than trying to raise a family without employment," agrees Mary Ann Monty, a longtime Smokey Point realtor and developer who built its new multistory hotel. "I think it's going to be better than Lynnwood. We're building up instead of just out. There's a lot more sign restrictions."

But others fear TRAP has made a pact with the devil, that every improvement draws still more growth, and that the lifestyle they moved north of Everett for is about to disappear.

ONE INNOVATION is to put a boundary on sprawl by a proposed transfer of development rights in the Stillaguamish River Valley, just north of Arlington. "If it works it will become a model for the state," says Vernon Beach, a farmer and developer working to push the program through.

Beach explained that the value of valley land as farmland is $2,000 to $3,000 an acre, while as housing it could fetch $8,000 to $10,000. "The pressure to break up a 50-acre farm into 10-acre parcels (the smallest that Snohomish County allows in the valley) is very great."

So officials are proposing that developers pay farmers what they might get for subdividing 3,300 valley acres in return for the right to build dense suburban housing clusters on 330 upland acres east of Arlington. Farmers get more money. Developers get more housing units. And the rest of us get to preserve the pleasant green valley that leads to old-town Arlington in return for developing 330 acres of woods.

The city also hopes to use growth-tax money to fix up its old downtown, in effect using big-box-blight at one end of town to pay for "Leave-It-To-Beaver" charm at the other end. "It's going to be a new-old community," says Arlington planner Paul Richart. "This is how the Growth Management Act accommodates growth."

Others are skeptical. "The philosophy is, 'We'll get their money and as long as they're a few miles away, it won't bother us," says Elizabeth Lynn of Arlington. "They glossed over the traffic problems."

Laura Wild of Lakewood, who first came to Marysville 19 years ago before moving farther north, remembers a newspaper story in which civic leaders said they wanted Marysville to become "the Lynnwood of the north — and truly, that's what it became."

"We're trying to get a vision," she says, pointing to Mill Creek's large-scale master plan as an example, "but a lot of people feel resigned."

"Most of us who came to this area wanted a small town, and rural kind of growth," says Gay Engelsen of Arlington. "There hasn't been a single person who said they want a Wal-Mart."

But growth is never invited, rarely resisted and barely thought-out. It is adjusted to, with freeway overpasses and widened arterials. Rome was a crazy-quilt of slums and palaces. Smokey Point and its neighbors are a collage of past decisions — Marysville's growing industry, for example, is being directed to the site where a NASCAR track failed to win support.

A plan for a new car dealership at the next interchange north of Smokey Point, called Island Crossing, was blocked because it's on a floodplain and dairy lands. But no one thinks that idea has gone away. Or that Seattle's northern edge has finally been reached.

At least there is now a point to Smokey Point. To paraphrase "Field of Dreams," the point is that they'll come whether you build it or not, but when you do build it they'll come even faster.

William Dietrich is a Pacific Northwest magazine staff writer. Steve Ringman is a Seattle Times staff photographer.