Thief stole more than 200 IDs, some from graveyards

Greg and Carol Paus' 6-year-old son, Jeffrey, died of a brain tumor in Whatcom County in 1961.

Forty-two years later they were devastated to learn that someone was using their dead son's identity to write a string of bad checks in Oregon.

"It brought back every memory, every old feeling," recounted Carol Paus, who along with her husband learned about the identity theft three years ago when a friend telephoned to say he'd recognized Jeffrey's name on a TV news report.

Jeffrey Paus was among scores of people — including many who died as children — whose names were stolen in what authorities think was perhaps the most extensive case of identity theft ever prosecuted in the Northwest. The man responsible for the scheme, Larry Steve Albert, used a ploy called "tombstoning," getting names, birth dates and other information by simply walking through cemeteries.

Authorities have compiled a list of more than 200 identities that Albert obtained from at least eight states during an eight-year period ending in 2004.

He ripped off merchants, banks and firms that verify checks for stores, they said. Albert's take has been tallied at more than $183,000, but investigators say the actual sum is likely much higher.

He was so adept at changing identities that when local authorities arrested him in Albuquerque, N.M., in 2004, he used a fake name, then skipped bail while they hunted for a man who didn't exist.

Albert's multistate scam finally ended in October when he was arrested in Whatcom County. Albert, a 62-year-old Texas native, pleaded guilty in December to mail fraud and to production of a false U.S. identification document — a Social Security card.

"I believe there was a great sense of relief when he was arrested," said Tim Lohraff, the federal public defender who will represent Albert when he is sentenced May 5 in U.S. District Court in Seattle.

Technically, Albert faces up to 20 years in prison. But given his lack of a criminal history, the likely punishment will be between two and four years, according to attorneys in the case.

Missing history

One of the strange things about the case, according to Joe Velling, a Seattle-based special agent with the Social Security Administration who headed the investigation, is that even after Albert's true identity was established, his past remains an enigma.

Authorities have determined he was raised in San Antonio and married in 1966, when he was 22 and his bride only 16.

"He was remarkably unremarkable," Velling said. "There were no clues, public records, work history, vehicle purchases, to his whereabouts after 1986. ... He just disappeared."

What drew Albert and his wife to the Northwest isn't clear. But authorities think he visited several graveyards in Washington state, including some in Whatcom, Cowlitz and Klickitat counties, to harvest identities.

Albert crafted fake Social Security numbers by changing the last series of numbers in the IDs of five of his six sons, Velling said. Albert then would fabricate phony Social Security cards and present them to banks.

A disturbing aspect to the case, the agent noted, was the banks' failure to cross-reference names and Social Security numbers to make sure they matched. The banks, Velling said, were primarily interested in making sure no bad credit was associated with the Social Security numbers Albert offered. Albert's routine was clever and effective.

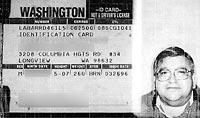

He'd go to a small town — places such as Medford, Hermiston and Lincoln City in Oregon and Walla Walla, Centralia and Longview in Washington. He generally favored small, independent banks.

"I'm new to the area," the likeable, gregarious man would say, using his identity of the day, Velling said. "I've heard good things about your bank."

Albert would produce a Social Security card and a driver's license or other papers to prove his identity, including dummied-up rental agreements that listed fake addresses. He'd usually deposit $100 into the new account. But he'd also have one more request, according to Velling:

"Since I don't have a permanent address just yet, could you please Fed-Ex the checks to the bank and I'll pick them up tomorrow?"

The banks were happy to oblige. They'd hand over the checks "with a big smile on their faces," Velling recounted. "And then, within a couple of days, he'd be writing bad checks. He would paper the whole town, and move on."

Because the account was new, merchants who tried to verify the checks were good got a green light, because $100 was on deposit and no checks had cleared yet.

He would repeat the scenario, sometimes two or three times a month, Velling said. Albert would write checks for groceries and other goods, and in some cases take the merchandise back for a cash return. He would hit up a variety of stores, including a number of chains such as G.I. Joe's, JC Penney, Sears, Target, Lowe's, Office Depot, Big 5, Staples, Wal-Mart and Barnes & Noble.

One of the secrets to his success, investigators say, is that Albert limited his frauds to relatively modest purchases at many stores. Posing as Jeffrey Paus, for example, he set up an account in North Bend, Ore., in October 2000 and wrote 48 checks totaling $4,712 over two days, fleecing merchants in the Medford area.

Because Albert was so good at covering his tracks — using fake identities to get other fake identities — leads invariably grew stale. At one point, Velling's bosses with the Social Security Administration pressured him to drop the case, the agent recalled.

"But I knew there were families and Social Security number holders who were victimized and we had to get this subject and stop the victimization of all these innocent people — alive and dead," Velling said.

The break in the case came after Albert got caught in Albuquerque in 2004, when he inexplicably changed his routine of hitting a town and moving on. Instead, he lingered in the area, returning repeatedly to the same REI store he'd already burned to seek a refund on merchandise.

REI auditors had started to discern a pattern. They alerted employees to be on the lookout for a man fitting Albert's description. When he showed up using the name "Joe L. Eddy" on Feb. 21, 2004, employees were prepared and contacted police.

Peter Novohom, then an REI assistant manager at the store, recalled Albert as "very friendly, very polite." In a recent interview, he described him as "very confident" but also said there was a "Hannibal Lecter" quality to him, "a look as if he knew he was smarter than you."

When Albuquerque police booked him, "Joe L. Eddy," who carried a New Mexico driver's license, told them his real name was "Larry Charles Albert," using a bogus middle name. He presented a Montana driver's license to prove it.

Albuquerque police entered his fingerprints into an automated system to see if there were any matches but got none because Albert had no criminal history.

Now that he was arrested, "Larry Charles Albert" asked an Albuquerque bondsman to contact his sister in Arizona to arrange for bail. Authorities later figured out that the "sister" was actually Albert's wife.

The wife put the bondsman in touch with another family member in San Antonio, who put up $3,250, or 10 percent of the bail amount. Albert then skipped out on his bail, and an Albuquerque judge issued a warrant for his arrest under the false name.

Meantime, the bail bondsman, suddenly on the hook for the $32,500 bail and motivated to do his own investigation, determined that the Larry Charles Albert identity actually belonged to a dead man.

Meantime, REI called police again, because Albert had never returned for his pickup, which was still parked in the store's parking lot.

Police had the vehicle towed. When they did an inventory, they noted the odometer: Albert had put 430,000 miles on the 1994 pickup purchased from a Bellingham Chevy dealer.

They also discovered a treasure trove of evidence, including a three-ring binder in which Albert had kept meticulous notes about the identities he used dating to 1986, meaning he apparently was defrauding banks and merchants 10 years before the 1996-2000 time frame covered in his plea agreement. They also found various identification documents.

As the extent of Albert's identity theft dawned on Albuquerque police, they transferred the case to the local FBI.

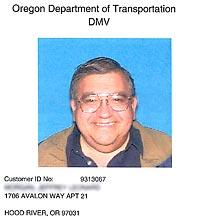

Last summer, New Mexico-based FBI agent John Fay contacted Glenda Kuenzi, an Oregon Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) employee who serves as a confidential records coordinator. As she absorbed the names Fay was asking about, she had an "ah-ha!" moment. Kuenzi contacted Velling, who quickly caught a flight to New Mexico.

As Velling examined various strands of evidence, several signs suggested Albert had returned to Washington after he'd fled New Mexico. A check of Washington licensing-department records showed that Albert's wife was living in the Bellingham area, as were two of their sons.

Velling established that the wife had briefly held a job in the area after Albert had left the Southwest. And Whatcom County was where Albert had gathered some of his names.

Velling is quick to note that tracking Albert down was a team effort. Besides Kuenzi, there was significant help from Medford, Ore., police Detective Sue Campbell, who plastered stores and DMV offices along the Interstate 5 corridor in Oregon with wanted posters showing pictures and descriptions of the anonymous man with many names.

There also was Lincoln City, Ore., police Officer David Strassburg, who dug out important details about how Albert acquired his identities.

On Oct. 24, federal agents staked out the home of one of Albert's sons and arrested Albert outside Lynden.

"The guy was good," Velling said of Albert's long run.

Meantime, the Pauses are among the families who have been invited to write down their thoughts for the judge who will sentence Albert. To have their son's name besmirched as Albert did still weighs heavy on them.

"It's about as low as I think an individual can get," said Greg Paus.

Peter Lewis: 206-464-2217 or plewis@seattletimes.com