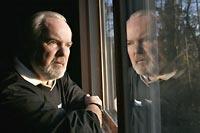

Gardner: "I've thought about the end"

His smile is warm, his hand steady and strong, and his mind clear and quick.

But balance, sometimes even walking, is a struggle. Booth Gardner, after 14 years of Parkinson's disease and its relentless assault on his ability to control his muscles, knows where this is going.

With death, as with life, Gardner wants to take charge.

After all, this is a man who always makes a phone call first thing in the morning, just so he — not someone else — will control the way his day starts.

"I've always done all the heavy lifting in my life; I've always made all the heavy decisions. I should be able to make the final one — how and when," said Gardner, a popular Democratic two-term governor who left office in 1993.

When Gardner, 70, announced Monday at a public dinner event that he planned to spearhead a campaign for an "assisted death" initiative in Washington, it took many by surprise, including those long active in the movement.

The timing may have been a bit early: Last month's U.S. Supreme Court ruling that upheld Oregon's law permitting doctors to prescribe lethal medication gave rise to talk of an initiative here, but so far there's no political-action committee, nobody to sign up volunteers, no headquarters.

Gardner's announcement galvanized the opposition to such a law, spurring talk of fundraising and feelers for aid from national organizations for the expected expensive and emotional political battle.

For Gardner, it was simply time to get busy on his next project, and leading an effort to legalize medical assistance in dying topped his list.

"I can bring to the table what virtually nobody else in this state can bring," Gardner said, struggling but failing to find a "humble" way to say that. "People like me, they respect me, they will get behind me on this issue. For those who have been working on this issue for a number of years, they've got a figurehead."

A figurehead with a very personal stake in the issue.

"Since I've had Parkinson's, obviously I've thought about the end," Gardner said Wednesday evening at his Vashon Island home. "I'm 70 years old now. Obviously, I've got limited time left. I want to keep busy, and when the day comes when I can no longer keep busy, and I'm a burden to my wife and kids, I want to be able to control my exit."

That won't be soon, he hopes. To help stave off the ravages of Parkinson's, he exercises four times a week, pushing himself hard.

But he has "hit the wall" on the ability of his medications to control his symptoms. He plans to have surgery soon to implant a sort of brain pacemaker he hopes will give him five more good years — busy years.

Most recently, he has been working to reshape the Washington Assessment of Student Learning (WASL). With that nearly complete, his restless mind began scanning for a cause that needed his help.

"It stopped on assisted death," he recalled. "I'd thought about it earlier when I was pretty sick. I thought about it again, and I said, 'That's what I want to do.' "

Buoyed by response

So there he was Monday night: Lights, cameras and a bully pulpit with the pews full. "There were a lot of people there, and everybody was asking what I'm going to do next. I knew what I was going to do next, so I thought, why not share it with everyone?"

Doing nothing was never an option, Gardner said. "It would be easier for me to say, 'I've done what needs to be done, you guys take over.' I don't mean to sound vain, but when I get involved in something, there's something about my personality, it creates a lot of other people," he said. "I'm very mediocre at everything else I do, but in politics I'm damn good. And I love it."

Like any Parkinson's patient, however, Gardner knows he's supposed to avoid stress and fatigue. So far, he admitted, he's not doing well on either score.

By Wednesday evening, he had already been down to Olympia twice that week.

"It's really ironic. My body is telling me to slow down, and my mind is saying 'Like hell!' Right now, the mind's winning out over the body."

He's heartened by the reaction to his announcement.

"I've had more response to this than when I won the governorship," he said.

A woman working on a highway crew told him, "That was real nice of you to take on that project; it means a lot to my family and me." A man followed him into a store to thank him, and callers have offered fundraising help.

At Compassion & Choices of Washington, a local right-to-die organization, Vice President Midge Levy said supporters of the cause welcomed the "very powerful support" from Gardner for an initiative, likely for the 2008 ballot.

"We certainly welcome it, but we need to organize ourselves," Levy said. "There is no organization, we have no PAC. ... But we're very grateful that someone of our ex-governor's stature has taken this up."

Opposition forms

On the other side of the issue, Dan Kennedy, CEO of Human Life of Washington, a right-to-life organization, has been busy since Monday contacting leaders of state and national organizations to "get organized and get accurate information out" in order to fight the initiative.

"We maintain that the arguments for assisted suicide are false arguments," he said. Patients in this state already have the right to refuse any treatment, and pain control is no longer an issue, Kennedy said.

"So the question for our culture becomes what does it [assisted suicide] do to medicine and what does it do to the larger society?" Inevitably, the "right" to assisted suicide becomes a duty for the vulnerable, he said.

Raising money will be a "major concern," Kennedy said. "We are on it."

The last time a right-to-die initiative came around in Washington, in 1991, Gardner was governor. But he smiles sheepishly when asked if he was active in the campaign, which would have legalized medical assistance to terminally ill patients who wanted to hasten death.

"It passed right by me," Gardner said. "I wasn't thinking about death then."

Most of the time that Gardner has had Parkinson's, he has been in Phase 1. Now, he's in Phase 3, with trouble with balance, stiffness, walking and restless limbs. Medication controls the symptoms most of the time, but it has serious side effects.

The scary thing about Phase 3, he says, is Phase 4.

"Because then you're debilitated. Then, the medicine doesn't do the job for you anymore. You need walkers. You need elevators instead of stairs. You need help going to the bathroom. You go from being independent to being dependent."

Beyond Oregon law

If Gardner has his way, the initiative won't say "suicide."

"Because suicide is not a dignified word. Suicide — that's people who jump off the Aurora bridge. This is not that. These are people who are good people, people who have just reached a point where quality of life is such that they don't want to go on."

Gardner says he'll push to go beyond the Oregon law, which allows doctors to prescribe lethal medication patients must take themselves. He wants a law like the 1991 initiative, which would have allowed doctors to give lethal injections to patients.

"I'd like to be able to say to my kids, ideally ... 'OK, you guys, this is Monday. My quality of life is gone. You have to do everything for me. I've had a great life, I've seen the grandkids grow up to be 19, 20 years old, I want to go. Let's make an appointment to go in Friday, say goodbye to each other this week.' "

Gardner, who's not religious, knows he'll face serious opposition. Even one of his children, he concedes, will disagree.

"He won't agree with me, but he'll respect my right. ... I've thought a lot about that.

"But when it gets down to whether it's his conscience or mine, I'd rather stick with mine," he said. "I believe what I'm doing is right."

Carol M. Ostrom: 206-464-2249 or costrom@seattletimes.com