The Gathering

THE WILD FEAST began, oddly enough, with a phone call to a self-described Wild Woman, a kayak guide and nature writer who lives with her potter husband in the Bellingham woods. I'd never met Jennifer Hahn, but was enchanted by her marvelous book, "Spirited Waters," about paddling solo from Alaska to Bellingham.

This genre, dominated by men, usually takes a Man-vs.-Nature approach and often includes back story about the writer's internal conflict with his father. Hahn had an excellent relationship with her father, a welder who held his clan together with love and memorable family trips after his wife died in a car accident when Jennifer was a baby. Once, in the Guatemalan jungle, when mud road ended at river's edge, he declared, "Well girls, Volkswagens float, don't they?" tied the Bug to his waist, waded in and towed it across with 8-year-old Jennifer on the running board.

Hahn's outdoor life — in harmony with nature — was thus launched. As an adult, her wanderlust led to culinary wilds. "I took my seat at the intertidal table," she writes about paddling through the Inside Passage in her early 30s. "Plucking mussels from white-whiskered headlands where waves soaked my sleeves I felt a kind of belonging — belonging not just to my appetite, but to the tide, moon, and booming waves. The boundaries separating us fell away like scales."

Reading, I felt a hunger. Irked by too many meals from cellophane packets, I craved a taste of fresh seaweed. My soul longed to escape the office. And the apocalyptic in me figured that given recent hurricanes, earthquakes and tsunami, it'd be prudent to learn Northwest survival gourmet.

So I called. Hahn was out paddling, of course, but called back from her cellphone, leaving a series of remarkable voice mails: I just peered down the blowhole of a gray whale!. . . Look at this sunset! Rippling magenta clouds reflected in the wet sand! At the end of each message, she'd mention a wild ingredient to harvest, a recipe to try.

What started as an afternoon paddle quickly escalated into a plan to gather and prepare a feast: Chowder with chopped kelp blades, potatoes and fresh fennel; spicy bull kelp pickles; salal and huckleberry relish; wild rice stuffing with freshly foraged chanterelles; the puffy tips of fucus seaweed sautéed with fresh limpets, wild salmon grilled in ruffled seaweed; grilled chitons, if we could find them; maybe urchin caviar on crackers; definitely a deep-sea chocolate pudding thickened with a nubby, red carrageen-rich seaweed called Turkish Towel.

In Northwest-potluck spirit, Hahn rounded up several friends who are guides, naturalists, wild foodies (or all of the above) to help. I volunteered to bring salmon, berries, fennel and potatoes. We agreed on a feast day when the tide would be low enough to harvest with enough daylight left to cook. It was several weeks away, thank goodness; I needed that time to gather ingredients.

Normally, I'd drive to the market with a list. This time, shopping didn't feel right. Something about the shrink-wrapped convenience, the scanner's bar-code beep, the ritual of paying with a plastic card that links food to a credit conglomerate rather than to the earth.

So, for two weeks, I led my usual overly efficient, processed, packaged life, relegating wild to the back burner.

SURELY, SOMEWHERE potatoes and fennel grow wild, but with 10 days until feast, my unruly garden was tempting. Not wild, but natural enough, and notches above Costco in slow-food snobbery. Outside, it was raining. Rain means soggy shopping bags, rising tempers, headlight glare if you're in a supermarket parking lot. But in the garden, the drip makes everything glow: pale fennel-seed heads, glistening leaf duff, tawny spuds nestled in the dirt (offspring of five moldy potatoes I'd thrown in the ground last spring). They'd do.

Two days later, the rain cleared. I drove an hour east on Interstate 90, then hiked a mossy trail alongside a gurgling stream to gather salal berries, the most widely used fruit among Northwest coastal tribes. Hahn's friend, Annette Dong, had told me of a salal thicket in a power-line clearcut on the way to an alpine lake. The berries dangled in neat rows amid varnished green leaves and white bell flowers. In the sun, the ripest fruits had softened, wrinkled and deepened to purply-black. They left a warmth on the tongue like resiny merlot. Nibbling the whole time, I took an hour to fill a container in the company of a squirrel munching orange berries off a mountain ash.

Another week in my cubicle, then it was time to find a salmon.

I took a little ferry to Legoe Bay on the west coast of Lummi Island, where, more than a thousand years ago, Lummi natives strung artificial reefs in the water to entice migrating salmon into nets, perhaps the oldest form of net fishing in the world.

In ancient times, the Lummis used war canoes and crafted underwater reefs from cedar-bark rope and marsh grasses. Today, 11 reef-net-salmon gears anchor offshore. They are a strange sight, these rafts mounted with gangly ladder towers rising 15 feet high. Swaying with each swell, a fisher perches for hours on a small cedar plank atop the ladder, scanning the water with the intensity of a hungry blue heron on a piling. Underwater, an artificial reef of plastic ribbon and line stretches between pairs of boats. When fishers spot salmon swimming into the reef, they pull up the net, spilling the fish into an underwater pen in the boat's center.

That morning, a squall had blown through, whipping up white froth and two-foot waves. Along came a school of sockeye, primed to find shelter from rough water. After two years roaming the Bering Sea and North Pacific, they were headed to their natal stream, fatter than even Copper River sockeye, with enough fuel to swim — without eating — 1,000 miles up British Columbia's Fraser River.

But first, the fish encountered a reef-net. They probably mistook it for a kelp bed in front of the real reef.

"You're up in the tower and suddenly there's a stillness," says Riley Starks, innkeeper, restaurateur and one of a dwindling population of reefnet reef-net fishers. "You see a school of fish as if in aerial formation, and your heart stops and you're hoping they go over the head and they DO and you yell: GO! PULL UP! Once you've got it, it's like a release. It's amazing. Addictive. Doesn't matter whether they're pink salmon or sockeye. It's as thrilling as seeing the orcas go by."

At 55, Starks has been a commercial fisher all his life. "Other types of fishing, you go where the fish are. It's competitive, and I'm a competitive person. So you can never tell the truth, y'know? I think that takes a toll. It did on me. With this fishery, (the salmon) might come here or there and you can't do anything about it and you can be happy for your neighbor. At the end of the day, you can tell the truth about the day's fishing."

The morning's catch was 63 sockeye, all males.

I bought a shimmering beauty with iridescent scales. Because it hadn't struggled and had been bled live in the seawater pen, the salmon would taste clean, Starks promised, no metallic tang of old blood. I will never know whether this sockeye suffered less in death than any other fish, but I could see it had been handled gently, and guessed it had lived a good life.

With wild harvest, you're forced to consider how creatures die and how they live, including yourself as a human being. Perched on that thin cedar plank at the top of the ladder, Starks can see below the water's restless surface. No fumes from diesel or old slaughter as on other commercial fishing vessels.

The reef-netter fishes, mind clear.

JENNIFER HAHN has been harvesting from the wild since she was a latchkey kid, hanging out in the Wisconsin woods until her father came home from work. "I found a lot of peace just sitting next to plants," Hahn says. She'd peer under the hood of jack-in-the-pulpits, squeeze red iodine drops from bloodroot to make tattoos.

Soon enough, the young girl was befriended by Florence, a white-haired neighbor who loved to collect things from nature to spray-paint gold and decorate with glitter. "It was like stumbling across the witch in Hansel and Gretel," Hahn recalls, "except this was a good witch, and the good things to eat in her house were wild harvest instead of candy."

On logs, they found fluted shelves of chicken-in-the-woods mushrooms, which they shredded and cooked like chicken. Under leaves, they unearthed puffballs, a mushroom that can grow bigger than your head. Florence fried them in margarine with a little salt and pepper.

"Even though they tasted a little plain," Hahn says, "I just loved Florence, and I knew they were good."

When Florence died, she left Hahn her collection of wild-edible-plant books. When Hahn came out to Bellingham as a student at Western Washington, she began to learn Northwest flora. "I want to know the plants of this area so when I go walking into the woods, I'm not alone. I'm surrounded by medicine, by food, by friends."

Hahn is the kind of woman who inspires men to build things for her. Her husband built her a writer's aerie with 13 windows to frame the forest. Her college boyfriend built her a kayak to take on weeklong paddles. Once, during spring break, a storm trapped them on Matia Island, white caps all the way to Lummi.

"We can't leave," he said.

"But school starts tomorrow, and we only have a little oatmeal!" Hahn wailed.

"Don't worry," he told her. "There's tons of food out here." They ate mussels, nettle soup, stews of green berries and currants. They were very aware of paralytic shellfish poisoning, but didn't get it. Gourmet it wasn't, but they didn't starve.

"I should just say," Hahn smiles, "that he never brought enough food on trips."

ON THE MORNING of the feast, we paddled into Bowman Bay at low tide, the surface smooth as a silver platter. Sweetly curved, this salt-water bowl is washed by Deception Pass to the north, ringed with Western red cedar and fir, punctuated by gray bluffs.

Hahn had flown in from northern British Columbia the previous day and was ebullient, cheeks ruddy, her hair as unruly as strands of seaweed tossed by storm. She doesn't braid or clip it back, instead using her salt-crusted tresses as a Beaufort wind scale. If her hair wafts gently up but settles back down, Hahn figures a 5-knot wind and lovely day to paddle; extending straight from her scalp and tugging at the roots, 20-knots, translate: "Get off the water."

At the moment, the weather and Hahn's hair are calm. As we paddle toward a kelp forest, Hahn narrates the intertidal landscape. Those dark blobs stuck on rocks are algae-covered plate limpets, gastropods you can eat like clams. That ribbony brown seaweed with twin seersucker stripes is sugar wrack; chew it; taste the natural sweetness of manitol; good in soups.

In the splash zone, that gray band resembling a dirty bathtub ring is sea tar, an algae eaten by periwinkles. Splotches of yellow paint on the rocks are salt-tolerant lichen. We see oozing anemone, red jellyfish, horsetooth barnacles, starfish, dogwinkles, crabs, an ethereal hooded nudibranch, a keyhole limpet wrapped by a scale worm.

Black Katy chitons cling to rocks. These plated mollusks have a large suction foot and look, from above, like tiny armadillos. Most tender in spring, black chitons are considered a delicacy by the Manhouset people of British Columbia, who traditionally soak the mollusks in red cedar boxes and pound the meat or throw them whole in the fire to blacken.

Grilled chitons are on our menu today, so I try to pry some off the rocks with a knife. It's tricky. Chitons have lived on earth some 500 million years, and they've developed keen survival instincts. At first touch, they clamp down, so bonded to the slick surface I can't slip my knife under shell. Worse, because I'm in a boat, every time I push against the chiton, I end up floating away from it. Worried about slipping, stabbing myself, dropping Hahn's knife or overturning my kayak, I give up. Well. That's part of the truth. Really, I feel queasy about killing something.

"When I have to kill something I've caught," Hahn later tells me, "there's sacrifice. If it's a king salmon, it's been traveling for six years in a huge migration. When I eat it, I feel aware of all that animal did, all it suffered. That fish is no longer going back to all the little haunts it likes to go to . . . There's nothing like holding a fish between my knees in the kayak and pushing a knife in its head and it's wiggling back and forth, and I'm aware I'm putting it in pain. I just try to kill it quickly. I try to use all its parts as much as possible. Even when I'm harvesting a licorice fern, I always say thank you.

"When I'm in a grocery store, I don't think twice about grabbing yams or handfuls of mushrooms and stuffing them in a plastic bag. When I'm in the wild, I'm saying I'm grateful the weather is calm, that the kelp bed is here, that I'm not tossed over in my boat. I'm grateful I know how to start a fire. I'm grateful, when all is said and done, I can take the animal's skin and bones and throw it back in the ocean so it can be used again. When I float on water and kill something and eat it, I'm aware it gave its life so I can continue with my life."

Thankfully, harvesting seaweed poses no major ethical dilemma, though I'm careful to leave the roots, or holdfast, when I tear off the leaves.

All around, there's an astonishing seaweed array: Olive bladderwrack, its bunny-ear floats filled with medicinal "fucus mucus," a soothing soak for tired feet. Brilliant green drifts of sea lettuce, Ulva, an algae only two cells thick that dries on the rocks in shiny cellophane sheets when the tide goes out. Turkish towel for the chocolate pudding. Iridescent rainbow seaweed. Long blades of nutritious winged kelp, alaria, excellent in stir-fries and soups. And fresh nori, a delicately ruffled crimson seaweed we eat straight off the rocks.

"Fresh from the sea," Hahn writes in "Spirited Waters," these seaweeds "taste like the primordial soup they come from: wet, salty, and full of vitamins and trace minerals."

What's most amazing is how seaweeds adapt, pounded by waves, roasted by sun, changing texture, form, color, salinity. Packed with protein and carbohydrates, many seaweeds turn a brilliant green during cooking as their chlorophyll sacs burst in the heat.

Plus, what other sea vegetable can be played like a musical instrument? Bull kelp has a bulbous float and a long hollow stipe. With proper lip technique, it's the ideal bugle horn to announce dinner.

BUT FIRST, we have to cook.

Hahn's wild-harvest mentor, Mac Smith, an ethnobotanist and carpenter, has brought his portable spice cabinet (lemon pepper, organic toasted sesame oil, brown rice vinegar, fresh lemons and limes) along with snorkel gear, which he uses to net a sea cucumber and a red sea urchin.

On a bluff above the beach, we set several Coleman stoves on picnic tables. Hahn's husband, Chris Moench, rolls the salmon in blades of bull kelp (nature's tinfoil), and grills it over medium coals, a spectacular sight when chlorophyll blasts suddenly turn the coppery ribbons emerald green.

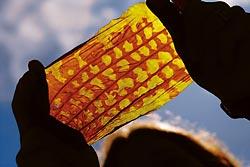

Peeling and slicing bull kelp changes my opinion of its character. Before, I'd seen the monster seaweed as sinister, its serpent tentacles ready to entangle my paddle, its float filled with enough carbon monoxide to kill a chicken. Armed with a vegetable peeler, I realize bull kelp is beautiful, versatile, sensuous. Its skin slides off in long, smooth strokes, revealing translucent olive flesh that gleams in the light. We pickle the jewel-like rings in turmeric, garlic, red onions.

The salty air simmers with mouth-watering smells: the deep smokiness of charred chitons; the tang of salal and cranberries exploding in a saucepan; the creamy warmth of chowder laced with frilly sea lettuce, ribbed alaria, feathery fennel; the woodsy aroma of chanterelle mushrooms that had whispered to Moench in a Doug Fir forest.

Smith fries little packets of fresh nori stuffed with rice and limpet. Dong extracts the urchin's egg sacs, five crescents the shade of ripe mango, from behind the creature's grinning denture-like teeth. Hahn dismantles the chiton's miniature dorsal plates, each a pearly boomerang, to later make into jewelry.

It could be the fresh air, autumn sun, or maybe just the novelty, but everything seems to taste and smell and look more vibrant. On the plank tables, the ruffled seaweeds glisten, prettier than any fancy restaurant garnish. Even the lemons, purchased from a store, smell so sharp and sweet their scent carries to the next picnic table.

Yes, nibbling before dinner, but only little snitches. Each offers a moment to savor, not like wolfing down a half-bag of chips and still feeling unsatisfied.

"It's still photosynthesizing when you put it in your mouth," Hahn says. "I can just feel that ocean surging into me, the energy of tides. To me, it's an ambrosia that almost makes me drunk with pleasure. I don't know where my body ends and the sea begins. It's so much more than protein or carbohydrates. I'm eating something that's millions of years of evolution."

This isn't an opulent meal, but it has its own decadence. So few of us ever get to taste a bite of the wild. It's a privilege to pluck kelp from a clean pulse of saltwater, to know what to harvest, how to cook it, to have friends to share. Perhaps each mouthful tastes precious because of what went into obtaining it.

Hahn gives thanks for the graciousness of the planet, the abundance of this country. There's a Tlingit saying: When the tide is out, the table is set.

Harvesting food in the wild, Hahn says, is about connecting with bigger cycles, losing yourself, gaining humility. "My gratitude starts to soar for being in this little human body for who knows how many years on this planet, then — poof! I'm gone!"Tide rising, we eat.

Paula Bock is a Pacific Northwest magazine staff writer. She can be reached at pbock@seattletimes.com. Tom Reese is a Seattle Times staff photographer.

To harvest, you need a state shellfish/seaweed license. Avoid polluted waters. Call Marine Biotoxin Hotline at 1-800-562-5632 or see the Marine Biotoxin Bulletin for latest reports. Warning signs aren't necessarily posted on beaches. And remember: Cooking does not remove shellfish toxin.

For information on wild harvesting classes, e-mail: mike@elakah.com.