Rainier's Terrible Lessons

TEN YEARS AGO, on Aug. 12, 1995, my only brother, Sean Ryan, died on the icy flanks of Mount Rainier. Barely 23 years old, Sean had just graduated college when he tumbled 1,200 vertical feet down the Winthrop Glacier while trying to rescue an injured climber.

Three and a half years younger than me, Sean was the baby in our close-knit New York family, the only son. Funny and witty, kind and generous, he was one of my best friends. His sudden death shattered our family's world. Instead of celebrating their 33rd wedding anniversary six days after Sean died, my parents spent the day planning his funeral. Two months later, our older sister, Sarah, was married in an emotional testimony of love pierced by Sean's profound absence.

Deaths on Mount Rainier are nothing new — an average of two to three climbers are lost each year. Hundreds of families across the world have suffered the whims of this unforgiving peak.

Yet, Sean died on Mount Rainier in the line of duty. Employed for the summer by the National Park Service, Sean was on an official rescue mission when he and Philip Otis, a 22-year-old volunteer backcountry ranger from Minnesota, slipped on the hard, impenetrable rime ice that had blanketed the mountain a few nights before. Scratches in the snow at 13,200 feet revealed the two young men fought fiercely to stop their slide, but attached by a rope for safety, they yanked each other down the steep slope to their premature deaths. They remain the only two Rainier rangers to have died on a rescue.

In June, I came to Rainier on a pilgrimage. With the 10-year anniversary of Sean's death approaching, I felt a need to mark his death with a grander gesture of remembrance than usual.

I came with another purpose as well. I came to ask questions I had been too afraid to ask: Why had Sean died? Had it been avoidable, and what, if anything, had those in charge of Rainier's climbing rangers learned from his death?

I arrived at Mount Rainier National Park on a cloudy, cool afternoon. The day before, I had flown from my home in Massachusetts. I had been here once before, a year after Sean's death, with my parents, sister and our husbands.

Together, with our fingers pointing at the peak, we had traced Sean and Phil's fateful route from 9,510-foot-high Camp Schurman up onto the the Emmons and Winthrop glaciers, then down the slick slope to their final resting place below Russell Cliffs. We had hiked the rocky ridge of Burroughs Mountain and descended into Glacier Basin, where we camped in the same spot Sean spent his first summer at Rainier as a backcountry ranger.

This time, I came alone.

After checking into the Paradise Inn on the south slope of the mountain, I explored some of the paved trails just outside the inn's front door. The massive mound of Rainier was enveloped in clouds, but I could sense it above me. I hiked to Myrtle Falls and then along the Golden Gate Trail. Large patches of dirty snow covered the meadows that in a few weeks would be exploding with vibrant wildflowers. When I hit hard snow, I turned around. I knew even slips on moderately steep snowfields can be dangerous. My family doesn't need two deaths on Mount Rainier.

That evening, I ate seared Pacific salmon in the inn's elegant dining room with Mike Gauthier, the park's supervisory climbing ranger. My contemporary at age 36, Gauthier had been Sean's climbing partner, mentor and friend. The two met in 1994, as roommates in the employee bunk houses behind White River Ranger Station.

Gauthier is the only park employee who has kept in touch with my parents. He introduced Sean to glacier climbing and mountaineering, and took him on his first ascent of Rainier. Gauthier encouraged Sean to become a climbing ranger, and he feels deeply responsible for his death.

"Sean and Phil's deaths really changed the trajectory of my life," he told me.

Their accident revealed deep flaws in how the park's ranger and rescue programs were run, from hiring criteria and training to rescue management, Gauthier said. He has spent much of the past 10 years trying to make right what he thinks was wrong.

As Gauthier and I finished our meal, I looked out to see the sun's setting hues of pink and orange reflected on Rainier's glistening white summit. The cloudy skies had cleared, and I finally saw what I came for.

I walked outside and as I gazed at this awesome, exciting, frightening, majestic and powerful mound of earth, I felt I should sob or scream, or pound my fists in rage on the asphalt. This is the mountain that killed Sean, denied him his future, battered his strong body so badly his cause of death was "multiple traumatic injuries."

Yet, the mountain seduced me. All I could do was stare in wonder at its beauty, and feel its draw, its magic. I felt myself wanting to go higher, and higher, and higher. Many times, I have thought Sean was foolish to do what he did, to take such risks. Now, I thought he would have been a fool not to.

SEAN FIRST CAME to Rainier in the summer of 1994. He was a volunteer backcountry ranger, working for the Student Conservation Association, a New Hampshire-based non-profit that assigns young interns to work in national parks and forests. It was the same job Phil held the following year.

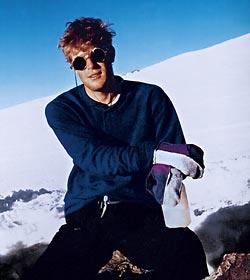

Sean arrived at Rainier a backpacker, rock climber and wilderness camper. He began backcountry adventures in 1990, participating in a 10-day wilderness course as part of his freshman orientation to the University of California at Santa Cruz. Sean had always excelled at individual sports, like snow and water skiing, and he soaked up the challenges of scaling rock walls and carrying a 60-pound pack.

During college he grew into a 6-foot-tall, lean and powerful young man. He spent his summers hiking with friends and family in Colorado, California, Utah, Montana and Wyoming.

But Sean was not a mountaineer. Rainier climbing ranger David Gottlieb remembers him more accurately as "an intellectual, an Ultimate Frisbee player, a wilderness aficionado."

Yet, I'm sure that in 1994, while patrolling Rainier's Glacier Basin, the mountain seduced him. On his days off, he hiked up the Inter Glacier to visit Gauthier, then a seasonal climbing ranger assigned to Camp Schurman. Together, they practiced crevasse rescues, glacier crossing and self-arrests. That first summer, Sean summited Rainier two or three times.

The next spring, the Park Service hired him as a climbing ranger, assigned to staff Camp Schurman with his good friend, Mike Gauthier. In late June, after his graduation, Sean loaded his pickup with gear and drove up Interstate 5 from California just in time for a summer-employee picnic at Longmire Ranger Station.

Sean and Phil were hailed as heroes after they died, and they were. Media accounts described them as idealistic young men willing to put their lives on the line to help another person. They also were portrayed as experienced climbers ready for the challenge before them.

Yet, three weeks after Sean and Phil were killed, an official inquiry into the accident implicated insufficient training along with faulty safety equipment, unreliable communications systems and extreme weather as contributing factors in their deaths.

Sean had summited Rainier perhaps a dozen times, but hadn't been on a rescue that summer. Phil, who worked in the lower mountain's backcountry, had reached the summit only once. Yet the two were sent to aid John Craver, who'd broken an ankle in a fall, because they were the only park employees at Camp Schurman when the emergency call came in. Sean and Phil, who were eager to go, could get to Craver more quickly than a team sent from Camp Muir, on the other side of the colossal peak.

The pair left Camp Schurman around 7:30 p.m. As they climbed, winds gusted up to 40 miles an hour and the temperature dropped below freezing, making what was normally for Sean a moderate trek much more dangerous. And Phil was using a defective pair of park-owned crampons, which Sean repeatedly radioed to officials were causing problems.

Sean made his last radio call at 11:25 p.m. Attempts to contact him throughout the night were unsuccessful. Yet, not until a second team of rescuers, who left Camp Muir at 1 a.m., reached Craver at dawn and found Sean and Phil missing did anyone begin to worry. Rangers aboard a helicopter spotted their bodies several hours later.

We will never know exactly what happened. Perhaps Phil lost his footing in the faulty crampons, or Sean was blown over by a gust of wind. Either way, the young men were not anchored to the mountain when one of them fell, and the force of the first man falling down the hard, slick 35- to 45-degree slope was too much for the other man to stop.

Mike Gauthier believes Sean and Phil fell shortly after their last radio transmission. Of all the people at Rainier, he is the most likely to know. A climbing ranger for 15 years, Gauthier has summited Rainier more than 170 times and led scores of rescues.

"That rescue situation would never happen again," Gauthier told me as we drank coffee at the kitchen table of the cabin he rents from the Park Service. Sean and Phil's deaths cast a spotlight on what was wrong with Rainier's climbing and rescue programs, he said.

Among the problems Gauthier identified were a lack of true mountaineering experience among the climbing rangers and a Park Service reluctance to provide rangers with the necessary equipment. Up through 1995, climbing rangers had to bring their own gear.

"The police department doesn't say to its recruits, 'Where's your bullets? Where's your gun?' when they show up for work," Gauthier said. "A pair of $100 crampons may have prevented this whole damn accident."

Beginning in 1996, Gauthier recruited serious climbers, those with multiple ascents of various peaks, to work at the park. That same year, the mountain raised about $100,000 by charging $15 to anyone who wanted to ascend Rainier. The new revenues were used to equip rangers with what they needed. Two years ago, the fee was raised to $30, generating about $240,000 annually to support the climbing rangers, among other things.

Gauthier also lobbied for more climbing rangers on the mountain and more rigorous training. Under his tutelage, rangers practice helicopter and rope rescues many times before their skills are tested in real life.

"We might still have hired Sean under our current system," Gauthier says, "but he would have been working with three or four other, more experienced people."

Sean and Phil's accident also led park management to revamp the entire Search and Rescue operation, from planning to logistics, says Park Superintendent David Uberuaga. Uberuaga was the park's chief of administration the day Sean and Phil died. He had never met them and was not overseeing the ranger program, and yet . . .

"I felt really guilty," he said, looking squarely in my eyes. "I wondered, 'What could and should we have been doing?' "

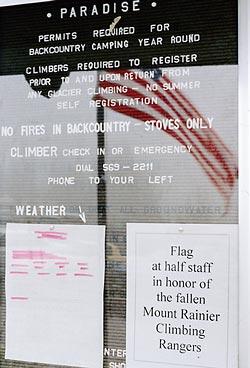

Chief Ranger Jill Hawk, who came to Rainier five years ago, says that rescue commanders stay on duty around the clock, which didn't happen the night Sean and Phil died. Determined to keep their memories alive, she told me of her plan to dedicate an official memorial to them at a new ranger station in Paradise.

Hawk also encourages climbing rangers to hold off on night rescues and to use helicopters whenever possible. In addition, she tries to drill into their heads that no rescue is worth dying for.

"It isn't an inherent decision that you go on a rescue," she says. "Park policy states that 'the protection of human life will take precedence over any other activity,' but that doesn't mean I have to put my staff at risk."

MY SECOND MORNING at Rainier I awoke just after dawn to clear blue skies and an incredible vista of the mountain's elusive summit. I strapped on my 12-year-old hiking boots and Sean's deep green Mountainsmith fanny pack and headed up the paved Alta Vista trail just across the parking lot. As I ambled along, the sun glinting off the ice fields, I could see above me the enormous Paradise-Stevens and Cowlitz glaciers, and the dark cliffs of Cathedral Rocks. I stared 9,000 feet up toward the summit and searched for signs of climbers making their way back and forth across the white expanse.

Later that morning, I learned that as I rested at Alta Vista, 5,000 feet above me a 29-year-old Port Angeles man had died sliding 1,000 feet down Gibralter Chute.

I thought of the climber's young widow hearing the dreaded news and crumbling against the door jamb, just as I had watched my mother do 10 years before. I pictured her telling her two small children their father wouldn't be home again. I knew what she had to do next — pick up the phone, notify people, arrange a funeral, put one foot in front of the other, and begin her new, sad life, now that her old one had been destroyed.

When climbers throw on their packs and strap on their crampons to ascend Rainier, they don't just carry their loved ones' photographs in their wallets. If they should freeze, fall in a crevasse, get crushed by an avalanche or tumble fatally down the ice, their wives, children, parents and siblings go with them. We survivors may not die on Rainier, but we are severely wounded, and while our wounds may get better with time, they never fully heal.

MY LAST MORNING at Rainier I drove the hour-long trip from Paradise to the White River Entrance, on the northeast side of the park. Overnight, rain clouds and fog had enveloped the mountain, and as I navigated the hairpin turns near Stevens Creek and then Silver Falls, I could see barely 200 feet in front of me.

I had planned to hike to Glacier Basin that morning to get as close as possible to Camp Schurman and to see, as I had nine years ago, where Sean died. But the odds of me seeing any part of the route Sean traversed were minimal that gloomy morning. And the three-mile trek to Glacier Basin would be through several inches of snow, which I was not prepared to tackle.

I parked outside the White River Ranger Station and went inside to meet David Gottlieb. He was talking with some other rangers, and when he introduced me as Sean Ryan's sister, the room grew silent. The rangers at Rainier all know of Sean and Phil, and their accident serves as a warning of what can happen, even to park employees.

I took Gottlieb outside and told him I didn't want to go to Glacier Basin anymore. I began to weep and was thankful he let me. I asked him to drive me up to Sunrise. I knew there was an incredible vista of the Emmons and Winthrop glaciers from there, and if the clouds parted, perhaps I could see Sean's route.

As we made our way up the winding road, Gottlieb told me two other families were at the mountain that day to honor two young men who had died a year ago on Liberty Ridge. I thought of those families and my own — my parents, my sister and our children, the three nephews and two nieces Sean will never know. We are all members of a club, a club of thousands, strangers intimately connected by tragedy on Mount Rainier.

The clouds never did part for me that last morning at Rainier. I did not see Camp Schurman, where Sean ate his final meal, or Russell Cliffs, where his broken body came to rest. But it didn't matter. I had made my pilgrimage. I had asked my questions, and I had heard the answers.

I do not believe my brother should have been allowed to lead that rescue attempt on Aug. 12, 1995, and I believe his superiors let him down. But I understand humans are not infallible. I am thankful Sean and Phil's memories are kept alive at Mount Rainier and that lessons have been learned from their deaths. Perhaps a climbing ranger will not die today because Sean died a decade ago.

Some day, I may return to Rainier, with my husband, son and daughter. Perhaps in five years. Perhaps in 10. I would like to show my children where their Uncle Sean died. I would like to sober them to the reality that young people do die. In the meantime, I will look for Sean in more familiar places — in the photographs that adorn my parents' home; in the waves of the Hudson River that lap the shore outside Sean's childhood bedroom; in my son's lean and strong 7-year-old body; in my daughter's penetrating blue eyes. I will look for Sean in my father, my mother, my sister. And in my heart.

He never strays far.

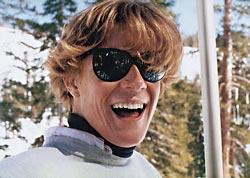

Ashley Ryan Gaddis lives with her husband and two children in eastern Massachusetts.