Beyond A Broken Boyhood

This piece, excerpted and condensed from the first six chapters of "Room Full of Mirrors: A Biography of Jimi Hendrix," by Charles R. Cross (Hyperion Books, August 2005), tells the story of Jimi's youth in Seattle.

JIMI HENDRIX WAS born the day after Thanksgiving, 1942, in King County Hospital, later called Harborview. At the time of Jimi's birth, Seattle was slowly emerging as one of the major western port cities, and in the process was becoming a destination for migrating African-American workers as well. The 1900 Seattle census reported only 406 African Americans, less than 1 percent of the population. But by 1950 the city's black population had ballooned to 15,666, representing Seattle's largest racial minority.

When Jimi was born, his father, Al, was a 23-year-old private in the U.S. Army, stationed at Fort Rucker, Ala. Jimi's mother, Lucille Jeter Hendrix, was only 17 and still a Seattle schoolgirl. They married on March 31, 1942, at the King County Courthouse in a quick ceremony, and only lived together as man and wife for three days before Al was shipped out to the service.

Jimi's lineage included Native Americans, slaves and white slave owners. His maternal grandfather was Preston Jeter, whose mother had been a slave in Virginia; Preston's father was his mother's former owner. Preston left the South after witnessing a lynching and traveled to Roslyn in Eastern Washington to work in the mines. There he found still more riotous racial violence when management brought in African Americans to break a strike by white miners. By 1915, Preston left for Seattle and started working as a landscaper. Jimi Hendrix's maternal grandmother, Clarice Lawson, also came from the South, and her ancestors included both slaves and Cherokees.

Most Seattle African Americans in the era lived in the Central District, and outside this neighborhood many townships had laws banning real-estate sales to non-whites. "It was a small enough community that if you didn't know someone, you knew their family," recalled Betty Jean Morgan, who would later date Jimi. Seattle's black community had its own newspapers, restaurants, shops and, most gloriously, its own entertainment district, centered on Jackson Street. There, nightclubs and gambling dens featured nationally known jazz and blues acts.

The Central District was home to Native Americans, as well as Chinese, Italian, German, Japanese and Filipino immigrants. It was also the center of Jewish life in the city, and a multiculturalism developed that was unique at the time not only in Seattle but also in the United States.

THE FIRST SEATTLE HENDRIX

Jimi's paternal grandfather, Bertran Hendrix, had also been born to a former slave and a white merchant who had once owned her. While working as a stagehand in a Chicago vaudeville troupe, he met and married Nora Moore.

Nora and Bertran arrived in Seattle when their all-black troupe, the Great Dixieland Spectacle, came to perform at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. They stayed for the summer, but eventually left for Vancouver, B.C., seeking more opportunity. They had four children, the last being James Allen Hendrix, who would become Jimi's father.

Al, as he was always called, left for Seattle in 1940 with $40 in his pocket. His first steady work was at the Ben Paris nightclub downtown, where he bused tables and shined shoes. Finally he found work at an iron foundry, hard physical labor that paid well. Al's only real joy at the time came from the dance floor. He had a brown zoot suit with white pin stripes, and over it he wore a beige, single-breasted coat. He was wearing that outfit, headed for a Fats Waller concert, when he first encountered 16-year-old Lucille Jeter.

Lucille was the youngest of the Jeter children, and she was a beauty. "She had long, thick, dark hair, which was straight, and a beautiful wide smile," recalled her best friend, Loreen Lockett. Lucille was proper and a bit immature, so the family was shocked when she became pregnant not long after dating Al. When they married, Al was too poor to initially buy her a ring.

Poverty also marked Lucille's life when Al was drafted and she was left in Seattle to fend for herself. She found work as a waitress in the unruly Jackson Street club scene, where she lied about her age. In clubs like the infamous Bucket of Blood, she served drinks and occasionally provided part of the entertainment. "She would sing," her sister Delores Hall recalled, "and men would give her tips because she was such a good singer."

Lucille soon became part of what hipsters called "the Main Stem." "That was the term used to describe where everything was happening," noted Bob Summerrise, one of Seattle's first black DJs, who owned a record store in the neighborhood. In clubs like the Black & Tan, the Rocking Chair and the Little Harlem, a colorful and rich alternative world existed, unseen by white Seattle. To Lucille Jeter Hendrix, working on Jackson Street was a life-changing event. The district became her milieu, and she was never again completely comfortable in more staid society.

A BABY NAMED BUSTER

When Lucille's firstborn arrived on Nov. 27, 1942, his Aunt Delores nicknamed the baby "Buster" because he looked like the cartoon character Buster Brown. At least part of the reason for the nickname was to avoid Lucille's choice of a legal name, "Johnny Allen Hendrix," which Al later worried Lucille had picked after a boyfriend named John. Thousands of miles away in the service, staring at a picture of his new son, Al worried about other romantic entanglements. Later he would legally change the boy's name to "James," but most in Seattle would know him as Buster or Jimi.

Over the next year, Lucille and her baby led a transitory life. She continued to work in restaurants and taverns, and had friends or her mother, Clarice, watch Buster. Freddie Mae Gautier, a family friend, hinted at occasional neglect. In a court deposition, Gautier told a lengthy tale of how one winter day, Clarice showed up at the Gautier house with a bundle in her arms. "This is Lucille's baby," she announced. Gautier recalled the baby was "icy cold, his little legs were blue," and his diaper was frozen solid with urine.

When the boy was almost 3, Lucille and Clarice took him to Berkeley, Calif., for a church convention. After the convention, Lucille returned home to work, but Clarice decided to visit relatives in Missouri. A church friend offered to keep the child. The arrangement was meant to be temporary, but it stretched on, and the child was still in California when Al Hendrix returned to Seattle in September 1945. While overseas, Al had begun divorce proceedings against Lucille. He spent the next two months in Seattle, then headed to California to get the toddler.

The family in Berkeley attempted to talk Al into leaving Buster with them, and an adoption would have been easy to arrange. Al was conflicted, yet also overwhelmed with paternal love. At the time, he wrote in a letter to his mother that Buster was "a fine boy and he is sweet. He's over average in smartness for his age, and these people are just crazy about him — everybody is." Al decided to take the boy.

EARLY DAYS IN YESLER TERRACE

In Seattle, Al and Jimi moved in with Aunt Delores to the Yesler Terrace housing project, the first racially integrated public housing in the United States. Lucille showed up soon after Al and Buster arrived. For the first time the three Hendrixes were in the same room, and by the end of the day, Al decided to abandon ideas of divorce.

By all accounts, the next several months were the smoothest the family would ever experience. Living with Lucille's sister, their expenses were minimal, so for once money was not an issue. Al was receiving small payments from the Army, and he and Lucille were able to go out on the town while Delores stayed with Jimi. Eventually, Delores became fed up with Al and Lucille's drinking and kicked them out.

Al then found work at a slaughterhouse, and they moved to a transient hotel in the Jackson Street area. Their modest room had only a single bed, which he, Lucille and Buster shared. They had a one-burner hot plate to prepare meals, and the room's only other furniture was a desk chair. They lived in this hotel room for months, until Al took a job as a merchant marine and was shipped to Japan. When he returned, he found that Lucille had been evicted. Al later said she had been kicked out after being caught with another man in the room; Delores disputed Al's version of events, but whatever happened it did not stop Al from taking Lucille back again immediately, and thus a pattern emerged: fights and separations were an integral part of their marriage.

In the spring of 1947, the reunited family moved to their first apartment in the Rainier Vista project in the Rainier Valley. The family's one-bedroom apartment at 3121 Oregon St. was so small that Buster slept in the closet. That closet became his retreat whenever his parents battled, which became ever more frequent, usually over money. Most of the jobs Al held during this period were manual labor, and none of them lasted long. They were living on less than $90 a month, with rent of $40.

Lucille was used to life on the Main Stem, and when Al came home from work, he was rarely interested in going out, so she would go without him. "When she came home," Delores recalled, "he'd be sitting out there drinking and he'd be mad. The next-door neighbor told me she'd hear fussing and fighting every night." Delores said Lucille would frequently have bruises when their fighting turned physical.

A more constant demon than jealousy was alcohol. Their house became a frequent party-pad: Jimi had to either leave or sit in his closet and overhear the racket.

MORE CHILDREN, MORE POVERTY

In January 1948, the couple had another boy, Leon. Leon's birth marked the apex of the family's good times. Al had a better job at the time, and he was so enamored of his new son that everything in their lives seemed improved.

Just 11 months after Leon was born, Lucille gave birth to another boy, whom Al named Joseph Allan Hendrix. Al was listed as the father on the birth certificate, though in his later autobiography Al denied paternity. Where Jimi and Leon were both tall and lanky, Joe was short and stocky, but looked enough like Al to be his twin.

Joe's birth was not a joyous occasion, as the baby had several serious birth defects. Jimi had turned 6 the winter Joe was born, and the family now had three young children to feed. Al and Lucille often fought about which one of them caused Joe's medical problems: Lucille blamed Al for pushing her when she was pregnant; Al blamed her drinking.

As Joe grew older, he needed significant medical care. Lucille frequently took Joe by bus to Children's Hospital in northeast Seattle, where she discovered the state would pay for most of Joe's medical needs, but she and Al would have to shoulder some of the expense. Al had finished electronics classes that year, but opportunities were limited for most African Americans, and the only work he could find was as a night janitor at the Pike Place Market.

By June 1949, the family hit a breaking point. The children had health issues related to malnutrition and survived only by eating at the neighbors, a habit that would soon become an almost daily occurrence. For a time the trio of children were sent to Canada to live with Al's mother, but by late 1949, Jimi was back in Seattle living with his Aunt Delores. He was living with her when he started second grade at Horace Mann Elementary.

The fall that Jimi turned 8, the Hendrix family added another child: Kathy Ira, born 16 weeks premature, and blind. Eleven months after her birth she was made a ward of the state and put into foster care. Al later denied paternity of Kathy, although her resemblance to him was as remarkable as Joe's.

A second daughter, Pamela, was born a year later. She, too, had health complications. Al was listed as her father on her birth certificate. Pam was given to foster care, though she stayed in the neighborhood and would occasionally see the rest of her family.

An even bigger issue was Joe's fate: Lucille held out hope he could live normally with the help of an operation, but Al was steadfast that they couldn't afford the procedure. Lucille began to drink more, and in the fall of 1951, she left Al.

In official divorce proceedings, Al was awarded custody of Jimi, Leon and Joe. This was really a paper formality: As they had been during most of Al and Lucille's marriage, the Hendrix boys were raised by Grandma Clarice Jeter, Al's mother in Vancouver, Aunt Delores, friend Dorothy Harding and others in the neighborhood. And despite being divorced, Al and Lucille still were together at times, as their passion play continued. Joe, however, was scheduled to become a ward of the state, the only way to get his medical expenses totally covered. Lucille and Al had to give up parental rights and leave him at Children's Hospital.

Al borrowed a car for the heartbreaking occasion. Jimi and Leon knew something was up when they watched their father pack their little brother's possessions and gather him into the car.

Joe certainly remembered the day. His mother held him in her arms on the car ride. "She smelled so good," Joe recalled, "like flowers." At the hospital, Lucille handed Joe to a waiting nurse. Joe then sat on the curb and, as his mother climbed back in the car, he began to weep. "My dad," Joe recalled, "never even got out of the car. He kept it running the whole time."

In the years to follow, Joe would frequently run into his brothers in the Central District. But Joe Hendrix never again saw Lucille.

WATCHING FOR WELFARE

Lucille quickly went off again, and Al was left raising Leon and Jimi by himself. "The neighbors started to take over watching us," Leon recalled, "because they knew what was going to happen — that welfare was going to take us away." The welfare department workers drove green cars, and Leon and Jimi learned to watch for those vehicles and beat a retreat if they saw one. Leon and Jimi would usually end up at neighbors around dinnertime. "Jimi and I used to be so hungry, we'd go to the grocery store and steal," Leon said. "Jimi would be smart: He'd open a loaf of bread, pull out two pieces, wrap it up, and put it back. Then he'd sneak into the meat department, and steal a package of ham to make a sandwich out of it."

In 1953, the family's fortunes improved when Al got a job with the city engineering department as a laborer. He purchased a small two-bedroom home at 2603 S. Washington St. Jimi was now attending Leschi, the most integrated elementary school in the city. Here, he met up with the boys who would become his closest childhood friends: Terry Johnson, Pernell Alexander and Jimmy Williams. Jimi occasionally joined Terry at Grace Methodist Church, and it was there that he had his first exposure to gospel music.

For entertainment the boys enjoyed a swim in Lake Washington or a cheap matinee at the Atlas Theater, where Jimi fell in love with the "Flash Gordon" serial and especially with the movie "Prince Valiant." The villain in "Prince Valiant" was called "the Black Knight," and Jimi and Leon would charge each other with brooms in make-believe jousting matches. That same broom was also fashioned into an imaginary guitar. Though Jimi had shown no particular interest in music up to this point, in 1953 he began to follow the popular charts and to play along to the radio, strumming the broom as if it were a guitar.

By 1954, acting on repeated complaints from neighbors, a social worker eventually cornered Al Hendrix. He was given two choices: His sons could be sent to a foster home or be put up for adoption. Al argued that Jimi, almost a teenager, needed less caring for, and thus should stay with him. Leon, Al's favorite by every account, would go to foster care.

Leon was placed in a foster home six blocks away with Arthur and Urville Wheeler. The Wheelers had six children of their own, but housed as many as 10 additional kids. They were church people and lived the morals of the Bible by treating all their children — even the foster kids — as equals. "Jimi was at our house more than he was at his dad's," recalled Doug Wheeler, one of the Wheeler sons. "A lot of times Jimi would spend the night, so he could have breakfast before going to school. Otherwise, he might not have anything to eat."

That fall, at Al's urging, Jimi turned out for junior football. His coach was Booth Gardner, who decades later would become Washington's governor. "He was no athlete," Gardner recalled. "He wasn't good enough to start; to tell the truth, he really wasn't good enough to play." Gardner felt sorry for Jimi and saw that the poverty in the family home was severe. One day Gardner stopped by and found Jimi sitting alone in the dark. "The power had been turned off," Gardner recalled.

When he wasn't playing football, Jimi roamed the neighborhood at all hours with little supervision. He soon knew every musician around, simply by listening for the sounds of their rehearsals. He'd hear music coming from a house, and as a curious boy, he'd simply knock on the door.

In 1956, during the first half of a year at Washington Junior High, Jimi earned one B, seven C's and one D. In the second half of the year, he had three C's, four D's and two F's. Jimi would have started eighth grade were it not for further problems at home. The bank repossessed their house, and Jimi and Al moved to a boarding house run by a Mrs. McKay. Jimi had to switch schools and went to Meany for eighth grade.

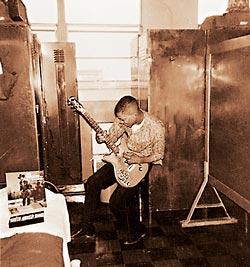

THE FIRST GUITAR

The McKay family had a son who played a beat-up acoustic guitar with just one string. When the guitar was discarded, Jimi retrieved it. To most, this instrument would have been a worthless piece of wood. Jimi, however, turned the guitar into a science project: He experimented with every fret, angle, twist and sound-making property the guitar had. He wasn't exactly making music, but he was making noise. "He only had one string," family friend Ernestine Benson observed, "but he could really make that string talk."

Like many teenagers, Jimi saw the guitar as a fashion accessory. Several of his classmates remember him taking the crippled guitar to school as a show-and-tell item. When asked if he could play, he replied, "It's broken." Still, he never let the guitar out of his sight. He kept it on his chest while he slept.

Jimi began ninth grade that fall and met Carmen Goudy, his first girlfriend. Like him, she was poor, yet even to Carmen, Jimi's poverty stood out. "He used to wear these little white buck loafers," she recalled. "He had a hole in the sole, so he'd cut these pieces of cardboard, and put that in the bottom of his shoes. He'd walk so much that he'd wear out the cardboard." Jimi rarely had a lunch to bring to school, so Carmen would regularly split her sandwich with him.

Carmen's sister was dating a man who played guitar, and Jimi would frequently hang at the man's feet, as if by simply watching someone play he could learn. Jimi had learned to supplement his air guitar with noises he made with his mouth. "He made sounds that approximated notes," Carmen said. "It was a bit like scat singing, but he actually could sing a guitar solo, not with words, but with sounds he made in his throat."

Other boys in the neighborhood began to get their first instruments that year. When Pernell Alexander acquired an electric guitar, the instrument was such a popular neighborhood attraction that boys would stop by just to look at it.

Jimi eventually acquired strings for his acoustic, and he strummed the guitar constantly, or at least until Al caught him. Jimi had been born left-handed, but his father insisted he write with his right hand. "My dad thought everything left-handed was from the devil," Leon recalled. This resulted in the almost-comic routine where Al arrived home and Jimi would immediately flip his guitar, keeping his song going all the while.

Jimi never took formal music lessons, but learned licks from neighborhood kids, most importantly Randy "Butch" Snipes. Butch could play guitar behind his back, imitating a T-Bone Walker move, and managed an admirable Chuck Berry duck walk.

AN "F" IN MUSIC CLASS

Guitar moves were one of the few things Jimi was learning, since his grades continued to decline. His mother had died that year of a ruptured spleen, and her death seemed to put a pall on the rest of his childhood. He and Al frequently moved, and he switched schools often. His report card for ninth grade showed him with three C's and five D's. If there was any good news, it was that he received only one F — ironically, in music. Jimi occasionally brought his guitar to school, but apparently the results did nothing to impress his music teacher, who encouraged him to consider other career paths.

He placed in the 40th percentile in standardized tests that year, though his poor marks were partly the result of his woeful attendance record. All the kids he had grown up with were headed for high school. He, instead, was ordered to repeat ninth grade.

On the frequent occasions that Jimi skipped school, he made his rounds, like a cop on a beat. His travels began to include the homes of a number of musicians, hoping they would give him tips. "In that era, guys were really open, and they would show you riffs and share stuff with you," recalled drummer Lester Exkano. "No one ever thought there would be any money to be made with music."

A couple of musical families were significant, not just to Jimi but to many aspiring players in the neighborhood. The Lewis family — with son keyboardist Dave Lewis and father, Dave Lewis, Sr. — inspired many. "They had this basement with a piano, and the door was always open," recalled musician Jimmy Ogilvy. "Dave, Sr. could play guitar, but mostly he was always encouraging. He had showed Ray Charles and Quincy Jones some licks." The Holden family, with sons Ron and Dave, and patriarch Oscar Holden, also held court in this manner. In many ways, this informal school — the school of rhythm and blues as practiced in the basements and back porches of Central Seattle — became Jimi's higher education.

Jimi had become proficient on his acoustic guitar, but what he most wanted was an electric model. "He was fascinated with electronics," Leon recalled. "He had rewired a stereo and tried to make it electrify his guitar." Al finally relented and bought Jimi a white Supro Ozark on time payments from Myer's Music. It was right-handed, but Jimi immediately restrung it leftie; that still meant that the guitar's controls were reversed, which would have made it difficult to master.

Jimi immediately called Carmen Goudy, and yelled into the phone, "I've got a guitar!"

"You already had a guitar," she said.

"No, I mean a real guitar!" he exclaimed. He dashed to her house. As they walked to Meany Park, Jimi literally jumped for joy with the guitar in his hands. "Remember," Carmen recalled, "we were kids who were so poor, we didn't get stuff for Christmas. This was like having five Christmases all rolled up into one."

The guitar became Jimi's life, and his life became the guitar. With the instrument in hand, his next fixation became finding a band. Over the next few months, Jimi would play with virtually everyone who owned an instrument in the neighborhood. Mostly it was informal jamming, and much of it was unamplified, since Jimi didn't yet have an amplifier. If he was lucky, one of the older musicians would let him plug into their gear, and he would wail away. He also didn't have a case for his guitar, so he carried it either unprotected, or in a paper dry cleaners' sack, which made him look more like a hobo than a slick guitar man.

That fall, Jimi had begun attending Garfield High School, but during his first semester he was tardy 20 days, and his grades were poor. He came to school primarily because there he reconnected with his friends from the neighborhood. Most of their daily discussions, sometimes in the back of the room during class, were about music. The school had a jukebox in the lunchroom and students were allowed to play it. Most neighborhood bands were informal, with revolving lineups depending on who was free on what night.

Jimi's very first gig was in the basement of the Temple De Hirsch Sinai, a Seattle synagogue. Jimi was playing with a group of older boys, in what was billed as an audition for his permanent inclusion in the then-nameless band. "During the first set, Jimi did his thing," Carmen Goudy recalled. "He did all this wild playing, and when they introduced the band members, and the spotlight was on him, he became even wilder." After the set-break, the band returned to the stage without Jimi — he'd been fired from his first professional gig.

His first significant band would be the Velvetones, formed by piano player Robert Green and tenor sax player Luther Rabb. The band regularly played on Friday nights at the Yesler Terrace Neighborhood House. Performing in the rec room of a housing project was hardly glamorous, and it didn't pay, but it gave Jimi and his bandmates a chance to experiment.

"They were like sock hops, really, and some kids would dance, but mostly you were playing to other kids who were also musicians," recalled local musician John Horn. "They were playing R&B, and some blues. Jimi was already something to watch — just the very fact that he was playing this right-handed guitar upside down was enough to keep you fascinated."

In June 1960, Al and Jimi moved yet again, this time to a small house at 2606 E. Yesler Way, just a few blocks away from Garfield High. Jimi ended his sophomore year with a B in Art; a D in Typing; F's in Drama, World History and Gym; and he had withdrawn from Language Arts, Woodshop and Spanish rather than fail. "He just wouldn't study," recalled friend Terry Johnson. "Then he'd get these failing grades, and that would further hurt his self-esteem."

When school started again at Garfield that next September, Jimi went to classes for the first month, but it was soon obvious he was never going to graduate. At the end of October 1960, he was officially taken off the ranks of Garfield students. "He was so far away from graduating, it wasn't a matter of a few credits or classes," recalled Principal Frank Hanawalt. "He had missed so much it was really impossible to make it all up."

Years later, when Jimi became famous and began mythologizing his own past to gullible reporters, he told a fantastic tale of how he had been "kicked out" of Garfield by racist teachers after he'd been discovered holding hands with a white girlfriend in study hall. The story was completely fabricated: Interracial dating was not unheard of at the school, and even the idea of Jimi sitting in study hall was enough to earn a chuckle from his friends and classmates. The truth was that on Oct. 31, 1960, Halloween, 17-year-old Jimi Hendrix flunked out.

Charles R. Cross, author of "Heavier Than Heaven: A Biography of Kurt Cobain," was editor of The Rocket, the Northwest music and entertainment magazine, from 1986 through 2000.

As family circumstances fluctuated, Jimi Hendrix was shuffled from school to school. Here he poses third from the left in the second row, with classmates from Leschi Elementary School. His best friend, Jimmy Williams, is to Jimis left.

HOWARD GISKE / SEATTLE TIMES FILE

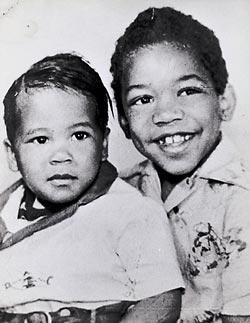

Jimi, right, and his younger brother, Leon, were often left to fend for themselves, wandering their Central District neighborhood and getting food from the neighbors.

JIM BATES / SEATTLE TIMES FILE, 2001

Most of my memories of Jimi are from here, says his brother, Leon, in front of the Central District house they shared as boys. The house has been the subject of legal wrangling amid plans to turn it into a museum.

COPYRIGHT DELORES HALL HAMM

Seven-year-old Jimi, in the striped shirt, stands in back of his brother, Leon, wearing the sailor outfit.

BETTY UDESEN / SEATTLE TIMES FILE, 1994

Al Hendrix posed before a photo of his son in 1994, when he was pursuing a federal lawsuit over control of his sons music.

![]() Q&A with Charles Cross: Author shines light on Hendrix biography

Q&A with Charles Cross: Author shines light on Hendrix biography

![]() Book review: "Room Full of Mirrors" clears up some of the haze about Seattle icon

Book review: "Room Full of Mirrors" clears up some of the haze about Seattle icon

This piece, excerpted and condensed from the first six chapters of "Room Full of Mirrors: A Biography of Jimi Hendrix," by Charles R. Cross (Hyperion Books, August 2005), tells the story of Jimi's youth in Seattle.

JIMI HENDRIX WAS born the day after Thanksgiving, 1942, in King County Hospital, later called Harborview. At the time of Jimi's birth, Seattle was slowly emerging as one of the major western port cities, and in the process was becoming a destination for migrating African-American workers as well. The 1900 Seattle census reported only 406 African Americans, less than 1 percent of the population. But by 1950 the city's black population had ballooned to 15,666, representing Seattle's largest racial minority.

When Jimi was born, his father, Al, was a 23-year-old private in the U.S. Army, stationed at Fort Rucker, Ala. Jimi's mother, Lucille Jeter Hendrix, was only 17 and still a Seattle schoolgirl. They married on March 31, 1942, at the King County Courthouse in a quick ceremony, and only lived together as man and wife for three days before Al was shipped out to the service.

Jimi's lineage included Native Americans, slaves and white slave owners. His maternal grandfather was Preston Jeter, whose mother had been a slave in Virginia; Preston's father was his mother's former owner. Preston left the South after witnessing a lynching and traveled to Roslyn in Eastern Washington to work in the mines. There he found still more riotous racial violence when management brought in African Americans to break a strike by white miners. By 1915, Preston left for Seattle and started working as a landscaper. Jimi Hendrix's maternal grandmother, Clarice Lawson, also came from the South, and her ancestors included both slaves and Cherokees.

Most Seattle African Americans in the era lived in the Central District, and outside this neighborhood many townships had laws banning real-estate sales to non-whites. "It was a small enough community that if you didn't know someone, you knew their family," recalled Betty Jean Morgan, who would later date Jimi. Seattle's black community had its own newspapers, restaurants, shops and, most gloriously, its own entertainment district, centered on Jackson Street. There, nightclubs and gambling dens featured nationally known jazz and blues acts.

The Central District was home to Native Americans, as well as Chinese, Italian, German, Japanese and Filipino immigrants. It was also the center of Jewish life in the city, and a multiculturalism developed that was unique at the time not only in Seattle but also in the United States.

Introducing his song "Hear My Train A Comin' " at a concert in 1970, Jimi Hendrix said it was about "a cat running around town and his old lady, she don't want him around. And a whole lot of people from across the tracks are putting him down. And nobody don't want to face up to it, but the cat has something, only everybody's against him because the cat might be a little bit different. So he goes on the road to be a voodoo child, and come back to be a magic boy."