The Genuine Article

FOR MORE THAN 100 years, if you needed rugged clothing, the Filson outfitting store in Seattle has been the place to buy it.

Thorn-proof, snake-proof, rain-proof, wind-proof, the waxed-canvas shelter cloth and heavy virgin-wool garments sewn right off the selling floor are as tough and durable as they come, earning the company a devoted following among the outdoor set. These folks don't bat an eye at paying $130 for a wool shirt; $219 for a sweater, $22 for a pair of socks.

Others are welcome to make it cheaper; that's not Filson's niche. Nobody shops at Filson for price; they shop there for quality, and a distinct, low-tech, old-Seattle aesthetic. Wax. Canvas. Wool. Cotton. Leather. Brass. There's not a scrap of Gore-Tex in sight.

Started in 1897 as an outfitter for stampeders on their way to the Klondike gold rush, Filson is as Seattle as cloud cover.

But the company has a new owner as of January — an investment outfit in (gasp) Southern California — and a Connecticut-based CEO who earned his pinstripes as an executive at Ralph Lauren Polo. And some changes are in store.

Oh, the double mackinaw that could turn back a bullet and waxed-canvas tin-cloth pants that feel like they could stand up all on their own will still be in stock. But a new, softer Filson "lodge" line — partly made overseas for the first time in this company's history — is coming.

What will they think of next, the duck-blind denizen might ask. Well, a line of women's clothing, for starters. And next? A few things for dogs. And ... pause... breathe... 14 more stores in major metropolitan areas.

All heralded with a national advertising campaign. We are talking not just hunting and fishing publications but the Wall Street Journal.

Those old sourdoughs must be turning in their mine tailings.

This is way, way new stuff for a company whose first catalog included tips for staking a mining claim, testing a colleague for death (stick with a pin), field-dressing a dog bite (burn with a hot coal) and reviving someone who's fainted (useful after that hot-coal treatment).

How the Klondike meets Connecticut is yet to be seen. But new CEO Doug Williams — raised on a family farm in South Dakota, actually, so don't hold Connecticut against him — says the loyal Filsonite has nothing to fear and a lot of new options to look forward to.

"This company will always have tin cloth in its blood. It will always have bridle leather in its blood, and it will always have Seattle in its blood," Williams pledged during a visit to the Seattle flagship store, wearing, it must be noted, boat shoes with no socks. This, the CEO of a company that sells barbed-wire-proof chaps.

ACROSS THE COUNTRY, purveyors of mass-produced garments have been cutting their throats along with their costs in a global race to the bottom. Filson managed to stay above the fray.

But the company is turning to overseas manufacturers for some of its new lodge line because that is where the investment in equipment and top-quality execution is found for some types of garments, Williams explains, adding, "What I want to do is make the best product, period. Then we'll source it appropriately."

And for many of the things the company makes, that will continue to mean making it in Seattle. Filson is one of the only clothing stores in Seattle, maybe for many miles, where buyers considering a purchase can look through a window at the people making the product in the next room.

Unionized, with the same health benefits as the executive vice president, about 80 sewers work at Filson. Some have been with the company more than 20 years. Most are female, and Asian.

Their work ethic is so ferocious, production manager Dennis Griffin says he has to hit the main electrical shutoff to get the sewers to take a break.

On average, they earn about $10 an hour, but they're paid by the piece. The workers set their own pace, decide among themselves what the flow of the work for the week should be, and even choose their co-workers — many of them family.

"We found it worked out much better that way," says Paula de Neui, production supervisor. "We just make sure they have what they need, and get the hell out of the way."

Good idea: These ladies might sew you to the table. Heads down, machines buzzing, theirs is the fluid mastery of top chefs during the noon rush.

"All the accolades we get are on their backs," de Neui says, "because they do it all."

Pausing just long enough to warmly shake a visitor's hand, Alice Leo, a native of Hong Kong, says she has worked as a sewer at Filson since 1977, and has a half dozen family members working at the Seattle facility. She's put three kids through college sewing — when not working at her husband's restaurant on weekends.

At 55, she is happy to be working just one job now. "I like it here, we all know each other, and sometimes I help the new people that can't speak English; I like to help them."

Some of what Filson makes can be made only here: Waxed canvas is tough to handle and hard to sew. Outsourcing is primarily for mass production, and Filson makes relatively small runs of very specialized clothing.

In an impersonal world, the Filson sewers are the equivalent of doctors who still make house calls. Bring in your battered, beloved piece of Filson gear and if they made it at the factory, they'll fix it. And some garments can be custom ordered — even discontinued patterns.

Assuming normal use, the store guarantees its products for life. A construction worker came in the store one recent day, still in his orange vest, waving a piece of Filson gear with a failed snap. He was out the door in minutes with a replacement and a smile.

FEW LOCAL COMPANIES have the following that Filson has. People from across the country and the world make a pilgrimage to Filson when in Seattle, stuffing new Filson purchases in their Filson bag for the trip home.

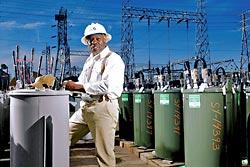

Then there's Jerry E. Lawson Sr., or Mr. Filson, as he is known on the job for his head-to-toe Filson regalia. "It's the full metal jacket, sister," Lawson says.

A utility-line crew chief for Seattle City Light, his Filson rig (including the bloomers) is just the thing for his work days spent underground in the city's utility tunnels.

The Filson fly-fishing jacket, it turns out, is perfect for a lineman: "You can still put your belt on without a long coat covering it. And the boots! They kept me warm all day long at 23 degrees.

"I go home to a good, sweet woman, and I want to be healthy. If I am going to take my body and put it out there in the elements, I want to have the best I can have. I wear the jackets, the pants, the vests, the boots, the socks. I've got the luggage... "

You get the idea.

Women? Despite not courting their affection, Filson has won many a heart among the fairer sex. Consider Cheryl Clavet, an outdoorswoman since she was growing up in northern Ontario, Canada, "and I always had lousy gear. If I had had Filson, I wouldn't have gotten frost bite."

Double layers of red plaid wool don't scare off the likes of Clavet: "Women who are serious outdoor women aren't going out in form-fitting clothes. They want it to be long-lasting and durable. But she eagerly awaits the women's line, due out in about two years, and goodies for her dog named (what else?) Filson.

No wonder. Today she cuts up her Filson shirts to make outfits for the pup, but that's perhaps to be expected for a dog owner who chucked her Saab convertible for a Jeep, all so Filson would be more comfortable.

"He looks so cute lying on my Filson jacket, too," says Clavet, she of the $335 Filson Wool Packer Coat with shearling collar. While she welcomes the new products, she has her qualms about Filson fiddling with its formula. "Why change a thing that has done so well for so many years and served so many?"

TO FILSONIZE: It's a verb. If you didn't know that, you haven't looked at clothing through this company's eyes.

For design folks at Filson, it's not an adequate vest until it has a concealed, drop-down seat of one-inch foam core zipped into the back, and padding along the spine area, exactly what you need for sitting on cold, hard ground against a tree. And there must be specialized pockets for a duck call, multiple shotgun shells, identification and wet, freshly killed game.

As the company designed a new sock for heavy wear, in stores this August, it added anti-blister padding in the heel; cushioning along the top to soften the grip of a boot; ribbing in the sole to massage the tender nether regions of the foot, and a shank of fabric over the outside to boost wear. (Only soft merino wool touches the skin.)

Also in the works: a rubber shooting patch to absorb up to 80 percent of rifle recoil that fits into the shoulder of a hunting jacket, "if we can figure out a way to get it in there that it won't be like a piece of armor," says Dick Holcombe, Filson's executive vice president.

The company's M.O. has always been to take whatever's out there and make it more durable, tougher. "Our tin cloth isn't canvas, it's canvas on steroids," Holcombe says. It's the legendary durability of Filson wear that has earned it that virtual cult following. "We don't drink the Kool-Aid, we lick the wax coating."

So the new lodge line, with its emphasis on soft, comfy, buttery, plush, silky and smooth, at times raised eyebrows on a recent afternoon when staff members got their first look at prototypes for the clothes.

"Too military," said one to a green down jacket. "Oh, that's so Mr. Rogers," said another to a wool sweater with suede patches.

"Oh, I love that hemline."

"Look at those twill lines!"

"Plastic! Oh, those buttons would never be Filson."

Nothing but natural materials, insists John Zannini, creative director for the company, also from Connecticut and recently of Banana Republic and Polo.

As he considered concepts for the new line, he searched old Filson catalogues and thought about what he himself wants to wear after a day of fly fishing for brook trout.

The clothes debut in the fall, in selected stores. The company has about 1,000 mom-and-pop vendors around the country, everything from Jerry's Rentals in Forks, Clallam County, to The Country Store on Vashon Island, where the arrival of a new Filson shipment is literally a banner day, with a sign hung facing the highway to alert the Filson faithful.

Those small vendors won't have the new line, because of their limited space; instead the company will target its larger "doors" — Nordstrom, in Seattle, and others.

The question for Filson, Williams says, isn't how to keep its loyal customers happy: That's where his vow to continue the company's core business comes in. The challenge is connecting with new customers, and the lives of Filson Fanatics when they are not "in the field," as the sporting sorts like to say.

Filson's customers are typically 44- to 55-year-old men, settled in their homes for at least 16 years, making their livings as entrepreneurs or executives. They are not chasing fashion, but they might want something a little softer than tin cloth at day's end.

The company wants its garments to be the first thing in the closet they reach for, not only when headed to the great outdoors, but to the club, the living room, the fireside. Once the pheasant is bagged, the big one caught, the work day over, why not still be wearing Filson? That is where the company hopes its new lodge line will come in.

"This is about putting something else in our customers' closet," says Holcombe.

"We are not going to be the next big thing. We are a certain thing, to certain people. We have a part of the closet now, and we would like to have a few more hangers. As long as they are cedar hangers, and say Filson on them, we are happy."

After the company has settled into the lodge line, it will tackle women's wear, then dogs. All, Holcombe says, without wavering from the company's commitment to quality and durability.

"A Filson dog nest. Canvas, bridle leather," he mused. "It will probably take a crane to lift it."

Lynda V. Mapes is a Seattle Times staff writer. Dean Rutz is a Times staff photographer.

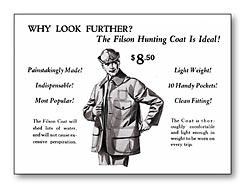

Clinton C. Filson, 1914 catalog