Group wants to save Snoqualmie smokestack

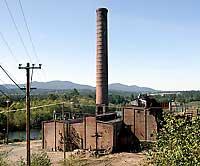

The faded, 211-foot brick smokestack and the ramshackle building beside it now stand alone on a plain near the Snoqualmie River.

But Harley Brumbaugh remembers when both structures were at the center of one of the country's largest lumber mills, and the mill town beside it was home to 1,200 people and a thriving timber industry.

He wants to prevent the last remnants of that past from disappearing.

Brumbaugh, 69, is one of a group of preservationists trying to prevent demolition of the smokestack and adjacent powerhouse, which began operating in 1917. Weyerhaeuser, which owns the property, has filed a permit with King County to remove the structures as part of a plan to clear the land.

Another mill smokestack at the site, built in 1944, was demolished in August.

"There was so much the mill stood for," said Brumbaugh, a prominent local musician and teacher. "To level it and go away seems like a desecration to the memory of the people that gave their lives in that mill."

The smokestack and powerhouse were given a reprieve earlier this month when the King County Historic Preservation Program requested they be considered for landmark designation. One of the largest lumber mills in the country, the Snoqualmie Falls Lumber Co. mill was only the second to use electric instead of solely steam power. The smokestacks and powerhouse were used to generate steam power to run motors that couldn't be powered by electricity.

Mill workers and their families lived in 250 homes built around the mill site and had their own hospital, school and community center.

Julie Koler, manager of the historic-preservation program, said the older stack and powerhouse seem to meet the county's landmark criteria. The next step is a formal review once an application for landmark status is filed by the Snoqualmie Valley Historical Society.

"There's a really high amount of community interest," Koler said of the structures, which are across the river from downtown Snoqualmie. "The mill really defined that area of the county for years."

A formal review will begin once an application for landmark status is filed by the Snoqualmie Valley Historical Society. After the application is reviewed by staff, a public hearing will be held, said Koler, followed by a final decision by the King County Landmarks Commission.

Even if the structures do receive landmark status, Weyerhaeuser could still demolish them if the company can show proof that preserving the buildings would impose an undue financial hardship, Koler said.

Frank Mendizabal, a spokesman for Weyerhaeuser, said the company will wait and see what happens with the landmark status before making a decision on how to proceed. Mendizabal said Weyerhaeuser has no immediate plans for what it wants to do with it.

During World War I, the mill supplied lumber for planes and ships. During World War II, women took over many of the traditionally male jobs as men went off to war. After the war, boom times revitalized the mill town.

But it began a slow decline in the 1950s, when many of its houses were moved across the river to the Williams Addition of Snoqualmie.

At the same time, the city of Snoqualmie has grown, ballooning from a population of 1,500 in 1997 to around 5,500 today. That growth has come almost totally from a massive new development called Snoqualmie Ridge, and new arrivals have little connection to the city's history as a logging town.

"Most people living in the valley today have no idea the mill town was there, no idea where the school was, the hospital or the mill store," said Brumbaugh. "In a way, that sort of hurts."

But not all longtime residents agree that the mill's remains need to be preserved.

Jim Gildersleeve, 63, worked in the mill as a youth 40 years ago but said it is time to move on.

"Some people have a historical attachment," said Gildersleeve, who runs an insurance agency in downtown Snoqualmie. "I'm in favor of Weyerhaeuser redeveloping the land for some other industrial use. We need more blue-collar jobs in the valley."