Suing psychic can see back pay in her future

"I was a sweatshop psychic."

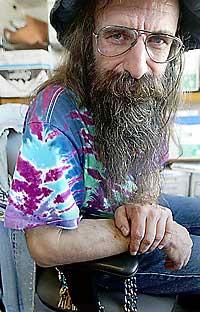

So begins the autobiography of Diane London, who told fortunes for about a decade on a 900-number hotline before being summarily terminated by a persnickety new boss named Samantha.

"Thrown out like an old orange," said London, who never saw it coming.

"They started hiring these people with names like Elvira and Moonshadow," London said last week, "and they didn't want a lot of the old-timers around.

London said it was devastating to her, both financially and emotionally. The former Seattle resident had helped countless callers end bad relationships, find their pets and meet the man of their dreams. How could she have enough bad karma to get fired?

But now London has turned the tables. On Thursday, she filed a lawsuit in King County alleging that the National Psychic Network, one of the biggest companies of its kind, broke the law by failing to pay the minimum wage and overtime. The company counters that London was an independent contractor and therefore not eligible.

The suit, which seeks an unspecified amount, is admittedly, well... unusual. But using arguments similar to those in the lawsuit, London has already won a decision from the state Employment Security Department awarding her unemployment pay.

Even to a nonpsychic, that's a positive sign.

"As soon as she started talking to me, I thought this was a good case," said Seattle attorney John Scannell. A character-about-town who was quoted years ago as saying that he aspired to be the "world's greatest Zamboni driver," Scannell has a growing list of underpaid clients — from exotic dancers to computer techies — stuck in the independent-contractor morass.

"Nobody ever challenges it because it never occurs to people," he said. It certainly occurred to London, who likens her psychic style to Judge Judy meets Dr. Ruth meets Ann Landers. Throw in a little Phyllis Diller, too, for this self-described "hot-tomato-turned-stewed-tomato" who pokes fun at herself and most everyone else.

London had tried to make a go of acting, but in the early '90s was encouraged by a friend to put her real skills to use. All she had to do was give a tarot-card reading over the phone to a National Psychic Network manager in Boca Raton, Fla., and she was in. She worked from her home in the Seattle area beginning in the early '90s, with brief stints in California.

"I'm a love expert and also the pet psychic," she said. "And I am very psychic." Not like some people who work on the psychic line, who, she confided, "are about as psychic as a potato."

The job entails a lot of sitting by the phone and waiting for calls, which the National Psychic Network routes to stay-at-home psychics all over the country.

Am I pregnant?

Is my grandmother going to die? And will I get her money?

Have I known my dog in a previous lifetime?

"To be quite honest, some of the people who call up are as sane as you and me and some of them have some real problems," London said. "Now, I hear voices, but that's part of my work." Ba dum bum.

London counseled callers who were abused by their husbands — but still think they're soul mates — callers who were on the verge of homelessness and callers who were dying of AIDS. She talked people out of suicide and told them where to find help recovering from incest.

"It's mainly women who have been abused by men sexually, financially, emotionally or physically." she said. "You become kind of an underpaid psychiatrist."

She earned 15 cents to 30 cents a minute, out of the $2-per minute or more charged by the National Psychic Network, she said.

Initially, London fielded 30 or more phone calls a day and earned about $3,000 a month. She even won company awards. But around 2002, things started changing, thanks to a rival psychic-hotline company best known for its spokeswoman, Miss Cleo, the turbaned, faux-Jamaican advertising herself as an "authentic shaman" on ubiquitous late-night commercials. Her company was sued by the Federal Trade Commission for fraudulent billing. And whispers spread that Miss Cleo's stable of psychics were reading from scripts — a no-no in the business.

"It gave all the people on the psychic line a black eye," London said.

Around this time, manager Samantha Ahrens came on board and tightened the reins at the National Psychic Network.

Now phone-in psychics had to sign affidavits swearing that they possessed psychic powers. London had to be logged into the call-routing system and available for readings at all hours. Ahrens complained about the way London did her readings and about her "sleepy voice."

She required London and her comrades to answer calls within two rings or risk a reduction in their call volume; gave strict orders to avoid talking about certain topics; and told them to always, always give "happy readings."

London protested. After all, if her psychic powers said a caller should leave her abusive husband, that's what London had to say.

Soon, calls came less and less frequently. By the end, she got as few as four or five a day, and earned under $14,000 her last full year there.

"It got to the point where I was barely making a living. I was essentially a prisoner in my own house just to survive."

Finally, during a confrontation in which London warned she was going to get back at management by burning black candles — only a joke, she claims — London was fired.

A black-candle termination might turn off some lawyers. Not John Scannell.

A former laborer, Scannell also drove the Zamboni on its slow serpentine sweep smoothing the ice at Seattle Thunderbirds games, a profession that made him famous to hockey fans statewide. He still calls himself "Zamboni John."

"We really got the crowd going for the games," he said. "I started the concept of rock-and-roll hockey. Now it's all over the place."

You might say his slow and circuitous route into the law was Zamboni-like. Years ago, as an organizer and shop steward for several unions, including one comprising city of Seattle workers, he was a plaintiff in a number of class-action lawsuits. One, against the city over denying benefits by labeling employees "intermittent" or "temporary" workers, took about 15 years to resolve but resulted in a $5 million judgment for back pay, plus millions more in pensions.

"That's why I decided I better become an attorney," Scannell said. "I'm dreaming up all these suits and the attorneys are the ones making all the money."

He never went to law school. Instead, he went through a unique internship program and passed the bar studying on his own.

"It's a rough way to go," he said.

In this case, his legal argument essentially boils down to this: By piling on more and more post-Cleo controls, management converted London from an independent contractor to an employee.

The amount of control is key. To call workers independent contractors, bosses have to keep their hands off as much as possible. Increase the amount of control too much and the workers become employees, said Mark Busto, an attorney and secretary of the Washington State Bar's Labor and Employment Law section.

Neither the psychic manager in Boca Raton nor a lawyer representing the company in Seattle returned phone messages. But they have maintained that London signed on as a contractor.

The difficulty in sorting this out is that it's not a black-and-white question. The Employment Security Department saw it her way, but a Superior Court judge could see it differently.

Scannell is confident. Although he insists he's a nonbeliever, he notes that London has predicted a win.

London, meanwhile, is home burning candles. Green, she said, for money.